In the first episode of our new season, Devin and Lauren look to a William G. Pomeroy marker in Westchester County to learn about American patriot Thomas Paine, his influence on the American and French Revolutions — and just how and why his body went missing. Where is Thomas Paine today?

Marker: Thomas Paine, New Rochelle, Westchester County, NY

Guests: Dr. Nora Slonimsky and Dr. Michael Crowder of the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies at Iona College

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Tom Paine and Revolutionary America, Eric Foner (1976)

The Thomas Paine Reader, Thomas Paine, with an introduction by Michael Foot and Isaac Kramnick (1987)

Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations, Craig Nelson (2007)

Teacher Resources:

PBS Teaching Guide: Thomas Paine: Writer and Revolutionary

C-SPAN Classroom: Lesson Plan: Thomas Paine and Common Sense

National Humanities Center: America in Class: Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to a new season of A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin lander, the New York state historian.

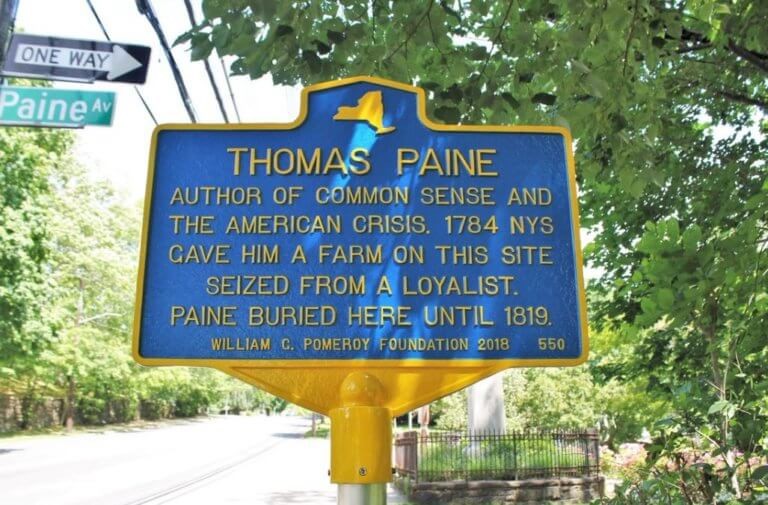

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. Today we start our new season with a William G. Pomeroy historic marker located in the city of New Rochelle in Westchester County. The title of the marker is “Thomas Paine,” and the text reads: “Author of Common Sense and The American Crisis. 1784, New York state gave him a farm on this site seized from a loyalist. Paine buried here until 1819. William G Pomeroy Foundation, 2018.”

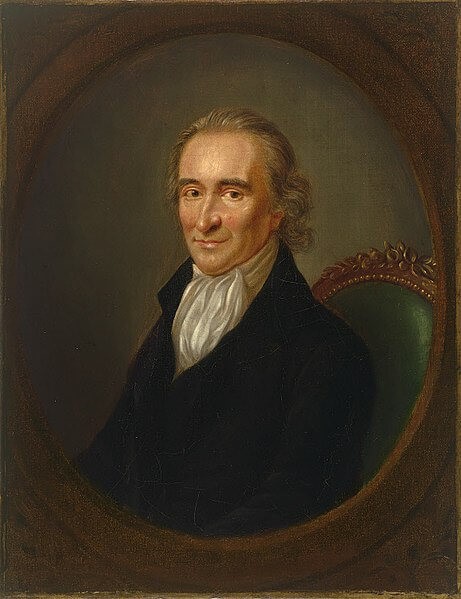

Devin: I don’t know if you’re like me, Lauren, but Thomas Paine is a name that I’ve heard a lot of over the years, certainly studying history – but I didn’t necessarily know that much about him. His biography, kind of who he was, what he did. I knew he was an author during the Revolution. I know he was a revolutionary. But beyond that, I didn’t know much about him until we started to dive into this episode. What I found out was that he was born in England, and lived there for the first 37 years of his life. In England, he was not very successful. In fact, he kind of had a tragic life: he lost a wife and child during childbirth, he was an unsuccessful corset maker, which is what his father’s occupation was. He was an unsuccessful tobacco shop owner, briefly a school teacher, a tax collector, and even more briefly, a privateer. But all of these things were not successful, and he didn’t certainly find riches doing any of these things.

But he did become politically active while living in England, and probably, at least from my perspective, the most important thing he did was chance into meeting Benjamin Franklin when he was on one of his trips to England, and the two became friends. Franklin actually suggested that Thomas Paine move to America and start a school – advice that he followed in 1774, though the school never materialized. Instead, due to his association with Franklin and his own interest in politics, Paine became involved in the revolutionary movement underway at the time. It could be argued that Paine was the main PR person for the independence movement to break away from Great Britain.

Lauren: I think that’s probably what most people know best about Paine. That’s certainly what I knew about before we started researching for this podcast – that he was the author of Common Sense, undoubtedly, the most famous pamphlet of the Revolution.

Devin: Absolutely. In fact, it was published in 1776, so the year that Revolution began, and in that Paine argued for independence and a republican form of government. So he was talking about not only breaking away from Great Britain, but instituting a form of government in which the people make the decisions, unlike a monarchy or any other kind of feudal system. And the real important thing, I think, about Common Sense and really all of his writings, is that he wrote it for a more general audience. It wasn’t a pamphlet for the elites written by the elites. It was written by somebody who really had his thumb on the pulse of the average person, the average farmer, the average merchant, the average person living in any of the 13 original colonies. And it was an immediate success. Some historians argue that it was the most popular work written in the 18th century. It’s hard to know the exact numbers that it sold, but we do know it was a massive success. And actually, Paine donated all of the proceeds from the sale of Common Sense to the Continental Army during the Revolution.

Lauren: So during the Revolution, Paine was a volunteer assistant to General Nathaniel Greene, though he didn’t earn a claim as a soldier. He was also famous as the author of The American Crisis, which was a series of 16 essays written over the length of the American Revolution, the first of which was reportedly read aloud to the troops at Valley Forge at the request of General Washington. And that first essay is probably the most recognizable to us today. It starts out with that famous quote, “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

Devin: In acknowledgement of his important contribution to the revolutionary effort, the New York state Legislature gave Paine a farm in New Rochelle that had been seized from a loyalist – thus the location of the Pomeroy marker.

Lauren: Though it was given to him in 1784, he really didn’t spend much time there, because he had an important role to play in other revolutions that were going on. And we spoke to two experts from the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies at Iona College who told us more about the next phase of Thomas Paine’s life.

Nora: My name is Nora Slonimsky, and Gardiner Assistant Professor of History at Iona College, where I also serve as the director for the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies, ITPS for short.

Michael: My name is Dr. Michael Crowder. I have a PhD in American history, and then I was lucky enough to begin working with the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies. And I’m now working on a new Paine biography, appropriately.

So Paine didn’t spend very much time at all [at the cottage], and in fact, was absent from the property from 1787 until 1805, when he permanently moved to the property. So for a 31-year period, Paine didn’t see it, because he was in Europe for the vast majority of that time period, first in England, and then in France.

Nora: Paine was not directly involved in the French Revolution until really 1791. And at this point, this was during that pivot, between what we might say is the first phase of the French Revolution, which was a reform for a constitutional monarchy, and the second phase of the French Revolution, which is the first republic. Paine did call for the abolition of the monarchy – he was very much a lowercase “r” republican, so he really did believe in as close to democratic rule as you could possibly get. And he was granted French citizenship and elected to the governing bodies of France at this period, but he did sort of break from what we might say the more radical group of the French Revolution in that, while he did believe that King Louie XVI should be removed from power – and that it was fine to put him on trial and find him guilty – he did oppose execution. He did oppose what ultimately happened to Louis and his family. And as a result, he ultimately found himself incarcerated. But he is ultimately released by late 1794.

He really grapples in this period, which is when you see the third phase of the French Revolution, or the rise of the Thermidors, Thermidorians. You see him really grappling with the realities of the Reign of Terror. Paine was indeed a radical, but he was not an unreasonable radical. He was willing to make compromise, he did not say that there should be no practical governing structures. And you see this particularly in his dedication, for example, of his 1797 pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, where he dedicates it to the government that comes after the republic, the directory.

So he’s not totally politically out of touch, but he does fall into a period of ill health. At this point, by the late 1790s, he is not in excellent health, and he does find himself in pretty hot water in England, because the work that he is doing, the publications he’s doing, are very, very pro-revolution. He basically says that Britain should become a republic as well. And he does advocate for united Irishmen to rebel. And he ultimately does return to America. Shortly after Napoleon’s rise, he does become somewhat disenchanted or dissatisfied with the French Revolution. He does ultimately critique Napoleon as well, but he waits ‘till he’s out of Europe before he does that. And that, I think, in so many words, really is the timeline of Paine’s relationship with the French Revolution. He maintained throughout his life its importance and its value. He is in no way as critical, it’s worth noting, of the different stages of the French Revolution, than he is, in some respects, to a perceived lack of follow-through of the more radical potentials of the American Revolution, or the failure of revolution to take root in England. He’s far more critical of those contexts than he is of France, but he is critical.

Devin (to Nora): How much do you believe his kind of fall from public grace, by the time he returned from France, had to do with his atheistic viewpoints? I know, of course, Teddy Roosevelt famously called him the “[filthy] little atheist” or something like that in the late 19th, early 20th Century. So I’m just interested in especially The Age of Reason, which was another popular pamphlet that he wrote after the American Revolution that really challenged organized religion.

Nora: So public opinion is a tricky thing. My understanding, and my read – and I am grateful to colleagues at the ITPS for sharing their knowledge with me – but it seems that Paine was not an atheist, that Paine was a spiritual person, that did have a belief in God. But it did not fit in with the belief system of many of his friends foes, believed, and that is why The Age of Reason, yet another term for what we now call The Age of Revolutions, or The Age of Empires, [is] where he doesn’t really fit.

By the time that Paine returns to the United States, the landscape is very different. This is no longer a revolutionary moment. In fact, the Constitution has been in place for over 10 years, the Federalist Party, or Federalist Coalition, depending on how you view that period, had been successful for the first two elections. And now another political coalition, the Democratic-Republicans had residential power under Thomas Jefferson. There had been government bureaucracy, there was a Supreme Court, there was a Congress, there was taxes. And the kind of energy, for lack of a better word, you might want when you’re trying to stir people to revolution is probably going to be a pretty different energy than you’re going to want around when you’re trying to get people to respect their government institutions, pay attention to the laws, and really instill a sense of civic duty to the relatively newly-formed federal government. Figures like Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson – across the political spectrum mind you, people from very different views on the major issues of the day, from slavery, to diplomacy, to taxation policies, and so on and so forth – there was a consensus that that type of revolutionary rhetoric was not necessarily as wanted. I wouldn’t go as far as to say he was unwelcome, but in some respects, this is why Paine developed many enemies. His radicalism – things like today, like universal basic income, or other forms of intense economic reform that he articulates in his pamphlet Agrarian Justice, his view of a secular world. If you’re looking for revolution, Paine is the person you call. Paine is the person you hope gets on Twitter. Paine is the person you want on your podcast. But if you are trying to create a very stable, authoritative governing structure, he might not be the person whose style you want.

Michael: He spent a significant amount of time in the very last years of his life at the cottage, just at a moment when he began to really wind down in terms of his writing. I wouldn’t say [his] retirement, because he never stopped writing, but there’s a noticeable decline in his writings, specially published writings [by that point]. So he only lived there for the very end of his life. He died in 1809. So it was his last resting place, I guess is the best way to put it.

Devin (to Lauren): So Lauren, the Pomeroy marker says that Thomas Paine was buried in that spot [at the cottage] until 1819. So he’s not there right now?

Lauren: No. Well, maybe, but certainly his complete remains are not there. And it’s an interesting story about somebody who dug him up in the middle of the night and shipped him to England.

Devin: I think this is the most fascinating part of this whole story. Obviously, the life and work of Thomas Paine is important, but understanding that he’s actually not there, and he’s not buried there because somebody came and stole his body, is really fascinating to me. And Dr. Michael Crowder, he told us a story that begins with local Quakers denying Paine’s burial request, and ends with a man named William Cobbett literally robbing his grave.

Michael: So he died in Greenwich Village, and just before his death, in his final will, he asked that the Quaker meetinghouse in Westchester allow him to be buried in their burying ground, on the basis that his father had been a Quaker. Thomas Paine had partially been raised as a Quaker. The Quaker meeting rejected this request, primarily because he’d written Age of Reason. In his will, there were no other stipulations except that, if he couldn’t be buried in a Quaker burial ground, he wanted to be buried on his property. And he was taken two days later and buried [there].

And because he was buried so quickly, there was very little time for the media to report upon his death, giving the impression that he died and nobody cared, when in reality, just given the obstacles to communication in the early 19th Century, his death was reported about a month after he was buried. And then there were much more voluminous commentary, both positive and negative. There was definitely interest in his death.

So William Cobbett is fascinating. He is an English writer-turned-politician who lived in the United States in the 1790s. In fact, he lived in Philadelphia, having emigrated from England, where he wrote as a partisan Federalist journalist and newspaper editor. He wrote under a pseudonym called “Pierre Porcupine,” in which, amongst many other people, he attacked Thomas Paine. And at some point, right around Paine’s death. So right around 1808-1809, Cabot realized that Thomas Paine, the person that he mercilessly attacked a decade to 15 years before, should actually be somebody that is celebrated and venerated. And he decided in the middle of the 1810s that what he needed to do was travel to New Rochelle to Thomas Paine’s farm, to dig up his bones so that they could be transported back to England, so that they could be properly buried, and a monument to Thomas Paine constructed in England to celebrate his influence, and his democratic principles. So William Cobbett traveled in 1819, and in the middle of the night, had a couple of hired laborers dig up Thomas Paine’s grave, store his bones in bags and then immediately go back to New York City and take the first boat out to England.

Devin: William Cobbett, he wrote about Thomas Paine after the publication of The Age of Reason, saying, “How Tom gets his living now, or what brothel he inhabits, I know not, nor does it much signify to anybody. He has done all the mischief he can in the world, and whether his carcass is at last to be suffered to rot on the earth, or to be dried in the air, is a very little consequence.” Again, he wrote this before Thomas Paine died, and then less than 10 years later, he’s robbing the remains of Thomas Paine, bringing them to England, thinking that they will help incite a revolution there.

One of the things that I find interesting is some of the ideas that William Cobbett had for raising the funds to build this memorial that he was hoping to build in England. And this is a quote from William Cobbett himself: “The hair of Thomas Paine’s head would be a treasure to the possessor, and this hair is in my possession. I intend to have it put into gold rings, and to sell them at a guinea apiece beyond the cost of the gold and the workmanship. These guineas shall be employed with whatever shall be raised by Paine himself in the erection of a monument to his memory. This shall take place when 20 wagonloads of flowers can be brought to strew the road before his hearse. It is my intention, when the rings are made, to have the workmen with me to give out the hair, and to see it put in myself. Then to write in my own hand a certificate on parchment, and to deliver it with each ring. This will be another pretty good test whether the remains of the great man be despised or not.”

Lauren: And as far as we know, he never went through with that, right?

Devin: As far as we know, he never was able to go through that.

Lauren: And he basically puts the bones in a box in his basement.

Devin: Right, where they remain until he passes away, and his heirs are left in debt. And we’re not really sure what happened to the remains of Thomas Paine, although there’s some evidence that they’re dispersed among friends and or family members of Cobbett. There’s also the suggestion that at least part of the remains are at the British Museum. There’s no way to really tell, even with modern testing today, because Thomas Paine was an only child who had no children. So having a direct descendant through DNA analysis would be difficult.

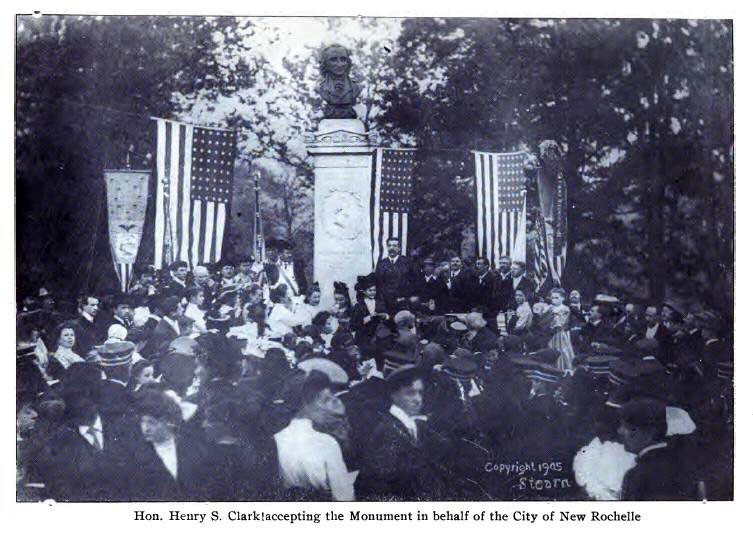

Lauren: What actually happens is that, fast forward to 1905, there actually was a grand monument erected in the memory of Thomas Paine – back in New Rochelle. And part of the application for the William G. Pomeroy historic marker includes a newspaper article that was printed about the dedication of the monument in 1905. And it gives some interesting clues about how the people of New Rochelle felt: there were several groups that were there to celebrate, including the sons of the American Revolution and school children. There were cannon salutes and patriotic songs being played – although there is a note that some of the decorations were lacking, because the people of New Rochelle were good Christians, and they still were a little bitter about the sentiments put forward in Paine’s Age of Reason.

Devin: It’s a fascinating article, Lauren, from the New York Times in 1905. And it says: “The Paine monument at last finds a home, accepted by New Rochelle with a preacher’s benediction. Town refuses to decorate, but turns out for the exercises. Part of the patriot’s brain to rest under the shaft.”

Lauren: Part of the brain?

Devin: That’s what it says. It says a small piece of what is purported to be Thomas Paine’s brain was placed under the monument when it was erected, and remains there to this day. Again, I have no idea how they know that it was Thomas Paine’s brain. But that is what they’re saying in this article. They said it resembled a small piece of dried putty.

Lauren: Interesting.

Devin: All of this shouldn’t detract from the fact that Thomas Paine was an important figure during the American Revolution, and played a hugely important role in disseminating the ideals of the Revolution to the average person who was alive during that time. It was a fantastical story, it was a lot of fun for me to research, but it was also an important opportunity for us to pay respects and give relevance to Thomas Paine himself.

Lauren: I think it’s important for us to remember that there’s so much mythology built up around the Founding Fathers that we tend to forget that they had personal lives, that they had shortcomings, that they had successes and failures, and that not everyone in their lives are going to continue in popularity. [Thomas Paine] comes from obscurity in England, he happens to meet Ben Franklin, he goes on to write the most significant pamphlet of propaganda during the American Revolution, which really convinces a lot of people that we need to call for independence from Britain. And then he kind of falls out of popularity for other beliefs that he has…But then you see that Iona College has an entire institute dedicated to the study of Thomas Paine. I wonder how many other radical players in the Revolution can claim that.

Devin: It’s weird, he seems to ebb and flow, like his popularity.

Lauren: Maybe his radicalism itself is what makes him such an interesting person. A lot of other major players in the Revolution seem to have a little bit more of an even keel – not that they weren’t radical, definitely they were all radical for their revolutionary beliefs, but Paine seems to have been over the top, and then he never really scales back. So maybe that has something to do with [it]. You can attach him to certain periods in our history where his ideas really can take hold.

Nora: What’s been really interesting to notice and to observe over the last several years, is really an increased interest in Paine. Paine is definitely someone [people have] gotten a little bit more serious about, and yet that curiosity really does cross the entire political spectrum. And it’s always tricky, right? Because the political spectrum of the late 18th Century is, of course, going to be quite different than the political spectrum today. And this is where it’s really important, I think, to both really understand what is distinct, and the real context of Paine in his in his worlds, right? What was very unique to that time, as well as what exactly that can tell us about our present day, and the connections that that has to our present day. So that’s just been really interesting to see how people find multiple different things about Paine to connect to.

The ITPS was founded at Iona College in 2011, really, to support and preserve the archival collection of the Thomas Paine National Historical Association, or the TPMHA. There’s a lot of acronyms in the world of Paine, so I do apologize to any listeners for that. But the TPMHA is still an organization that’s around today. It has a really, really fascinating history. You have really incredible artifacts. And then you have items from the antebellum period where Paine’s legacy begins to be disputed in the 1820s and 1830s. And then you have the history of the TPMHA itself: its minutes, its records, its correspondence. The understandings and arguments about Paine are very much about Paine, of course, but they’re also about the bigger period. These figures and these historical events are very much about their own time, but how we remember them, and how we think about them, tells us a lot about our present moments as well.

Michael: The cottage sustained a significant amount of damage when Hurricane Ida came through the New York City / Westchester / Connecticut region, and it had just underwent a significant remodeling in the two years prior. In 2018-2019, and into 2020, there was a significant amount of work put into the cottage by the Huguenot & New Rochelle Historical [Association], the local historical society which owns it, to bring it back to a state that would most closely approximate the state in which Thomas Paine lived in the cottage. They did a wonderful job, and they’re working to recover, but they are accepting funds from anybody who’s interested in donating because of the damage. They have many different kinds of public programming that’s intended to engage the community – not just about Thomas Paine, although of course, he’s significant, but just to engage the history of the Revolutionary era and the early republic more broadly.

Devin: Thank you for listening to the first episode of our new season of A New York Minute in History.

Lauren: This podcast is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support by the William G. Pomeroy Foundation.

Devin: Our producer is Jesse King. I’m Devin Lander.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts.

Until next time, Excelsior.

(Until next time, America.)