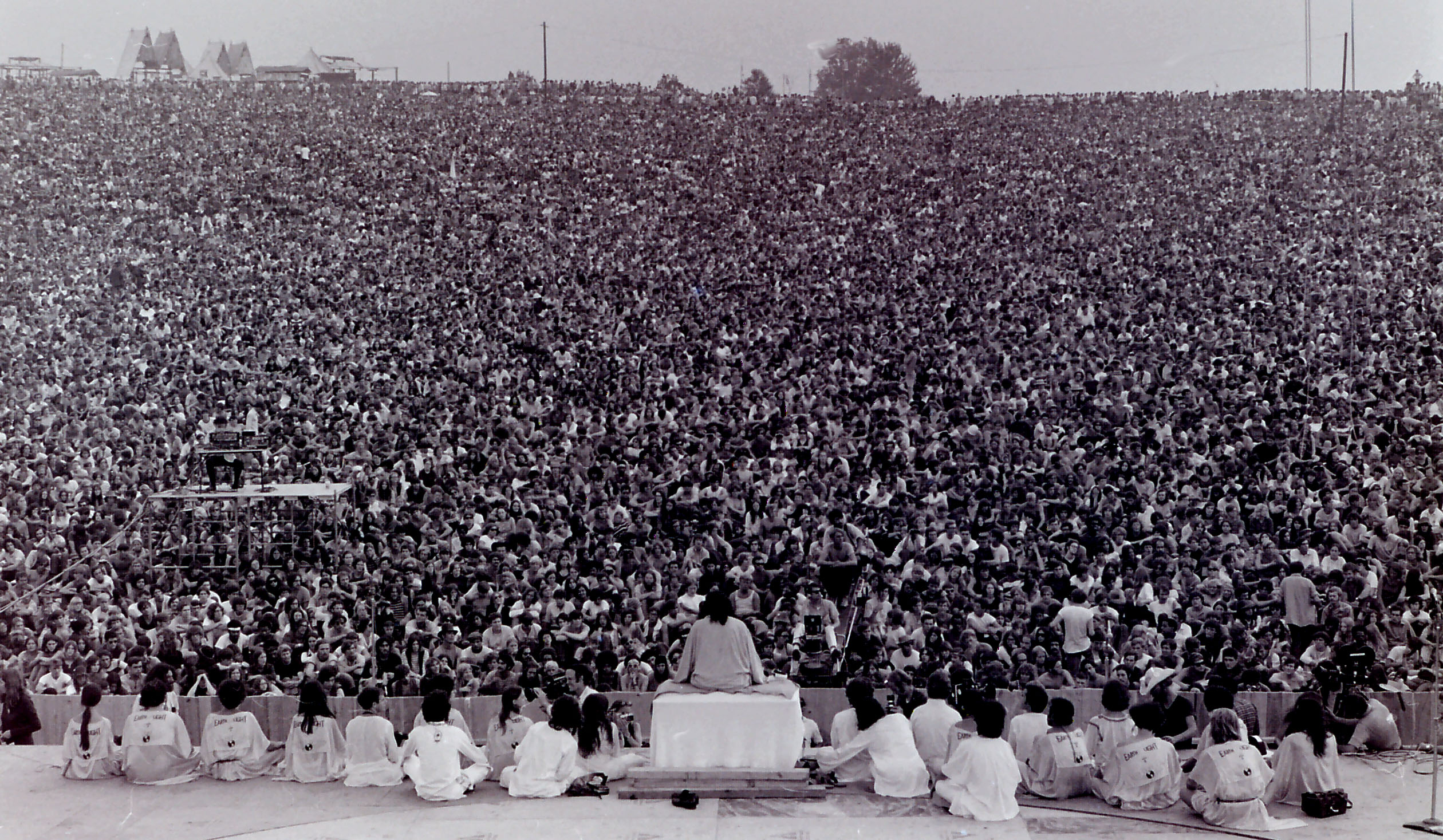

Now regarded as one the most iconic cultural expressions of American society, the Woodstock festival of 1969 served to encapsulate the spirit of the 1960s counterculture movement. Despite Woodstock’s continued popularity 50 years after it was first held, the complexities that led to its creation and lasting social impacts are often overlooked. On this episode of A New York Minute In History, co-hosts Devin Lander and Lauren Roberts speak with author Mark Berger, Karen Quinn – the Senior Art Curator at the New York State Museum, art collector Arthur Anderson, and Wade Lawrence – the museum director of the Museum at Bethel Woods, about various aspects of Woodstock such as its lesser known origin story, its role as an emblem of counterculture, and it’s often-overlooked connection to the Woodstock Arts Colony.

The episode also includes a compilation of archival WAMC interviews with some of the performers and organizers of the 1969 Woodstock festival.

Woodstock Festival

The idea of the now iconic Woodstock festival of 1969 was originally conceived by four men from New York City named Michael Lang, Artie Kornfeld, John Roberts, and Joel Rosenman. Lang and Kornfeld both held experience in the music industry with Lang having headed the Miami Pop Festival of 1968 and Kornfeld having served as the youngest vice president at Capitol Records. Roberts and Rosenman were wealthy New York entrepreneurs interested in making a new investment. When they combined forces, the idea was proposed to create a recording studio in Woodstock, NY under the name Woodstock Ventures.

Woodstock, NY had been known as a popular center for artists long before the existence of Woodstock Ventures. The rural town was regarded as reflecting the “back-to-the-land” spirit that was becoming increasingly popular in the 1960s and attracted famous musicians, such as Bob Dylan and Van Morrison, seeking a peaceful place to create.

In order for Woodstock Ventures to fund their recording studio, they decided to host a concert. Although the fundraiser would be named for the town of Woodstock, due to a series of issues faced by the organizers, the festival would actually take place more than 50 miles away.

Finding a suitable location to host the festival proved to be one of the biggest challenges facing the promoters. Due to there being no suitable locations in the small town of Woodstock, the group began looking in neighboring areas. Although they were able to find several possible locations, Woodstock Ventures received pushback from local communities. At one point they tried to secure a spot in Saugerties, NY only to be refused a permit and later tried to host the event in Wallkill, NY but were denied once again.

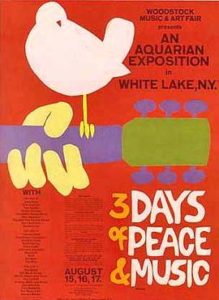

The group’s luck changed upon meeting Elliot Tiber. Tiber initially offered the land of his parent’s motel for the group to use, however, this was turned down as the site was deemed unacceptable for the large crowds expected. Tiber then suggested meeting with a real estate agent from the area as they would know of more suitable places nearby. This idea eventually connected Woodstock Ventures with Max Yasgur, the owner of a large dairy farm in Bethel, NY. Yasgur agreed to let his farm be used in exchange for a reported $50,000. Despite the event not being held in Woodstock, it continued to be advertised under the name of the town. Due to the festival’s official title being, “Woodstock Music and Art Fair presents: An Aquarian Exposition” which would be shortened and popularized by the media simply as “Woodstock.”

Woodstock Arts Colony

In certain circles, Woodstock was already iconic well before 1969. In 1902, The Byrdcliffe Arts Colony was founded near Woodstock by Jane Byrd McCall and Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead and became the first intentionally created year-round arts colony in the nation. Now the oldest arts and crafts colony in the United States, Byrdcliffe was originally formed in opposition to the popular industrialization movement of the early twentieth century and has continued to serve as a home for American counterculture.

Byrdcliffe Arts Colony is located just outside the town of Woodstock on the side of Mount Guardian, surrounded by the Catskill Mountains. Its environment has attracted a variety of artists, writers, and musicians seeking to find inspiration in their surroundings.

Many of the early events and people within the colony have inspired the actions of later generations. In 1915, the first Maverick Festival was put on by Hervey White, founder of the Maverick Community. The festival was a one-night event featuring music, dancing, and costumes. It became increasingly popular in the community and continued for several years before being shut down due to attracting too many people. It has often been regarded as a forerunner to the Woodstock Festival of 1969.

In conjunction with the growing music scene of the colony, the creation of art also flourished. One of the most prominent artists was George Bellows who spent his first summer in the arts colony in 1920. Bellows belonged to the Ashcan school and often created realistic works, as opposed to more popular academic approaches of the time. In fact, the arts colony became known for encouraging diversity within artistic styles, leading to a wide range of creations produced there. Art collector Arthur Anderson recently donated 1500 objects from almost 200 artists who lived in the Byrdcliffe Arts Colony to the New York State Museums, “Historic Woodstock Art Colony Exhibit” which will be running from November 10, 2018 to December 31, 2019.

Thanks to author Mark Berger, Karen Quinn of the New York State Museum, art collector Arthur Anderson, and Wade Lawrence of the Museum at Bethel Woods for their help with this episode.

Sara Casazza, an intern at the New York State Museum, contributed to this episode.

Music used in this episode of A New York Minute In History includes “Begrudge” by Darby, “Hash Out” by Sunday at Slims and “Kid Kodi” by Skittle.

The oral history of Woodstock drawn from WAMC interviews with Wavy Gravy, Graham Nash, Melanie, Michael Lang, Stephen Stills, Robbie Robertson of the Band, Richie Havens, Arlo Guthrie, Leslie West of Mountain and Pete Townshend of the Who included the following songs: “Going Up The Country” by Canned Heat, “With A Little Help From My Friends” by Joe Cocker, “For What It’s Worth” by Stephen Stills, “Freedom” by Richie Havens, “Coming Into Los Angeles” by Arlo Guthrie, “Blood of the Sun” by Mountain, “Lay Down” by Melanie and “Woodstock” by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

A New York Minute In History is a podcast about the history of New York and the unique tales of New Yorkers. It is hosted by Devin Lander, the New York State Historian, and Saratoga County Historian Lauren Roberts. WAMC’s Jim Levulis is the producer. A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC Northeast Public Radio and Archivist Media.

Support for this podcast comes from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation®, which helps people celebrate their community’s history by providing grants for historic markers and plaques. Since 2006, the Foundation has expanded from one to six different signage grant programs, and funded over 875 signs across New York State and beyond … all the way to Alaska! With all these options, there’s never been a better time to apply.

The Foundation’s programs in the Empire State include commemorating national women’s suffrage, historic canals, sites on the National Register of Historic Places, New York State’s history, and folklore and legends. Grants are available to 501(c)(3) organizations, nonprofit academic institutions, and municipalities. To apply for signage at no cost to you, or to learn more about the Foundation’s grant programs, visit WGPfoundation.org.

This program is also funded in part by Humanities New York with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this podcast do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.