On this episode, Devin and Lauren visit New York’s oldest continuously operating courthouse, located in the City of Johnstown in Fulton County. Built in 1772 by Sir William Johnson, the Fulton County Courthouse has seen the transition from British colonial rule to the establishment of the United States, and 250 years of legal history. Among the important judges to hold court at the courthouse include Daniel Cady, the father of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was heavily influenced by legal cases which demonstrated how few rights women had in the 19th Century.

On September 8, 2022, the courthouse will officially celebrate its 250th birthday, with the New York State Court of Appeals conducting its business there for the first time.

Marker of Focus: Suffrage Pioneer, Johnstown, Fulton County

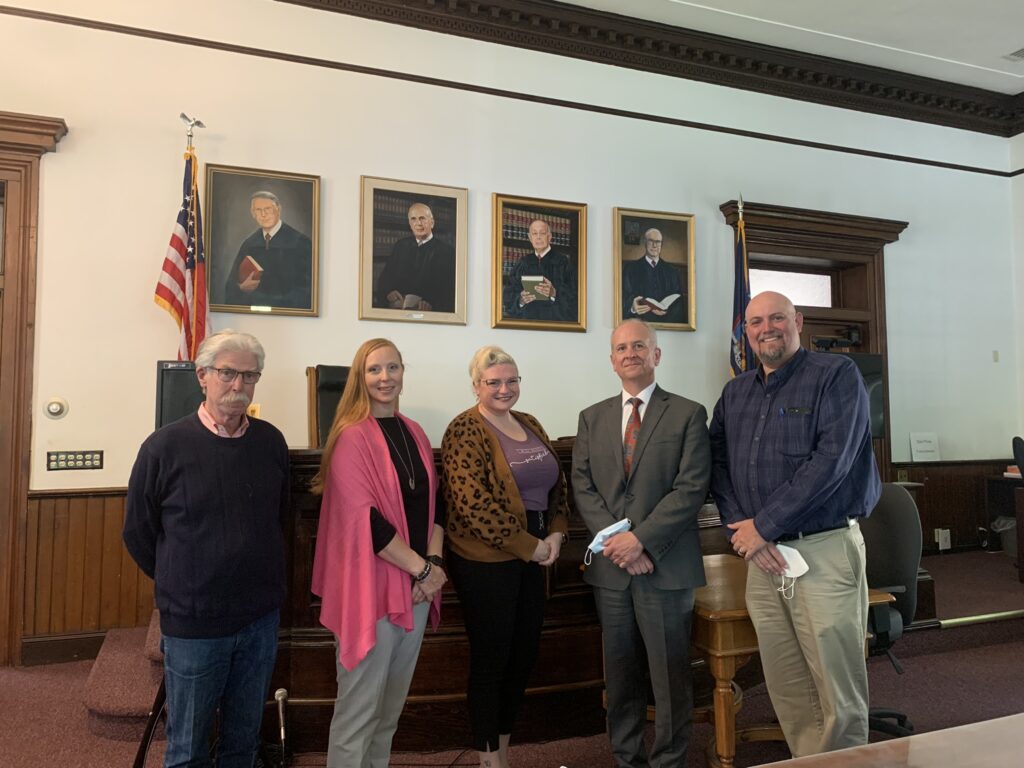

Guests: Hon. J. Gerard McAuliffe, Jr., Fulton County Family Court judge; Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt, retired New York State Court of Appeals judge; Samantha Hall-Saladino, Fulton County historian; Noel Levee, City of Johnstown historian

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Historic Courthouses of the State of New York, Julia Carlson Rosenblatt and Albert M. Rosenblatt (2006).

Fulton County Courthouse, The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life, Lori D. Ginzberg (2010).

Building a Revolutionary State: The Legal Transformation of New York, 1776-1783, Howard Pashman, Esq. (2018).

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On this episode, we’re going to focus on a William G. Pomeroy marker located in the city of Johnstown, in Fulton County. The marker sits on the lawn of the Fulton County Courthouse, located on the corner of West Main Street and North William Street, and it reads: “Suffrage Pioneer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1815-1902. Her father practiced law here in early 19th Century, inspiring her fight for women’s rights. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2017.”

I’m guessing most of our listeners have heard of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and know about the incredibly important role she played in the women’s suffrage movement. But they may not be familiar with her life prior to the famous Seneca Falls Convention which took place in 1848, and produced the Declaration of Sentiments, a document which listed freedoms and rights that women should be entitled to, including the right to vote. In Elizabeth’s early life, she grew up in Johnstown, New York, where her father Daniel Cady practiced law. It was her exposure to his law practice, and the firsthand experiences Elizabeth had in his law office and in the courthouse, that showed her how poorly women were treated in the eyes of the law in the early 19th Century.

Now, that’s a huge claim to fame for any courthouse. But for this particular courthouse, its association with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her father Daniel is only one piece of the puzzle in the big picture story it has to tell.

Devin: That’s right, and the William G. Pomeroy Foundation marker is only one of the markers that exists in front of the Fulton County Courthouse. There is another one that was erected by the State Education Department. And it reads: “Erected 1772, Only colonial courthouse in state of New York, first court General Sessions, Tryon County, September 8, 1772.” In effect, it is saying that the Fulton County Courthouse is the oldest continuously operating courthouse in the state of New York, and has been in operation since there was no state of New York, and the state was in fact a colony of Great Britain.

Lauren: And if I’m doing my math correctly, it means that the Fulton County Courthouse should be celebrating a very important anniversary this year. To learn more about the early days of the courthouse and the Johnstown area, we had the privilege to visit the Fulton County Courthouse on a beautiful spring day, where we got to see this historic building firsthand. We spoke with Fulton County Historian Samantha Hall-Saladino.

Samantha: So we are on the ancestral homelands of the Mohawk people, part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. When the European colonists settled here, this became known as Tryon County. It was formed out of Albany County. It was named after the governor at the time, William Tryon. This area really developed under the oversight of Sir William Johnson. He was of Irish extraction. He had come to the Mohawk Valley in 1738, at the request of his uncle, Peter Warren, to help him clear the land that he had purchased on the south side of the Mohawk River. But Johnson realized that the trade routes are on the north side of the river, and so he decided to buy his own property and cultivated a relationship with the local Native Americans, specifically the Mohawk, and then started dealing directly with the merchants in New York City, cutting off the merchants and business folks in Albany. So he was not very popular, to that extent. He had a very robust military career, and because of his role as Indian agent, he was given the title of baronet, and he actually purchased the land that became Johnstown from some Mohawk at Canajoharie. So it was not a land grant, he purchased directly from the Native Americans.

Devin: Why did he want to create an actual town? What was his idea behind creating Johnstown?

Samantha: I mean, from my perspective, right? We don’t know what exactly he was thinking. But he certainly continued to improve himself, build up his name, and accumulate land. I think he wanted a legacy in a sense, and it was his idea to create Tryon County so that Johnstown could be the seat. Almost immediately after, Johnson went to work in building a courthouse and a jail. He contributed £500 of his own money to the building of the courthouse. And I think for Johnson and the residents here, it represented westward expansion for them. They were “conquering the wilds,” and they were bringing British law and order to what was wilderness to them. Of course, after the American Revolution, the British Royal Governor was not very popular among the remaining people living in this area, and so they chose the name Montgomery County, after General Richard Montgomery, who was killed in Quebec. And then in 1836, the county seat was moved from Johnstown to Fonda. The Johnstown folks were not so appreciative of that, and a charge was led to create a new county out of Montgomery. One of the leading people in this charge was Judge Daniel Cady, the father of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They chose the name Fulton, after the engineer Robert Fulton. He was a relation of Daniel Cady’s wife. And so Fulton County was born in 1838.

Devin: What was the situation here as the colonies moved closer and closer to revolution?

Samantha: So Sir William Johnson actually died in July of 1774. And I think as modern historians, we like to play that “what if” game, like “What if Sir William Johnson hadn’t died right as things are heating up with the American Revolution?” Because he was a loyalist. His son, Sir John Johnson, who essentially took his place after his death, was also a loyalist. But there were people in this area who were considered rebels, I guess you’d say patriots. There were things happening here.

In May of 1775, General Philip Schuyler ordered the 3rd New Jersey Regiment to Johnstown to quell some of the loyalist activities that were happening here, and in an attempt to capture John Johnson. By the time they arrived, he was long gone and fled to Canada. But the militia paraded through Johnstown, they took possession of the courthouse, of the jail, of St. John’s Church, which is just across the street from where we are today. They set up their tents and their camps right on the lawns out in front of the courthouse. And if you are familiar with Johnson Hall, you are familiar with the banister, along the staircase, which to this day has displayed signs of damage, like somebody smashed something along the railing of the staircase. And that damage was caused most likely during this time, when the 3rd New Jersey Regiment was here and stationed at Johnson Hall. In 1776, the New York provincial convention ordered all the lead weights from the window at the Tryon County Courthouse to be removed by the local militia, so they could melt it down and use for ammunition. But despite all this, the courts continue to meet during this time.

Devin: Now one of the things that I think is really fascinating is the fact that this was an existing courthouse during British colonial rule. We have to think about the transition that would have happened in 1776 with the Declaration of Independence, and then the following American Revolution. The entire system was being challenged by the colonial patriots, as they were known, against British law, in some regards – at least against the government.

Lauren: It’s neighbor against neighbor, brother against brother, a true civil war when everyone is trying to figure out which side they’re on. So it sounds like things could have become very upside down in the court system when you transition from the British court to the Patriots court. Is that what happened?

Devin: It’s a question that I really had in my mind, too. So to learn more about the history of our courts, I sat down with Albert Rosenblatt, a former judge on the New York State Court of Appeals, and a historian of our courts.

Albert: It was, I’m going to say, at the start, all but seamless. When New York wrote its first constitution in 1777, a year after the Declaration of Independence, New York declared that it will follow the English common law. And what else would they follow? They wouldn’t follow the common law of Mars or Saturn or some other unrecognized jurisdiction. The common law would work because the common law was, in a way, the grandparent of our own Bill of Rights. When we speak of free speech, freedom of religion, our concerns about search and seizure, those derived from British common law – which is interesting, because England and the United States would probably reach the same result in a great many civil liberties inquiries. We, however, rely on words like “due process,” and words to that effect, but in a written constitution. They have those impulses from an unwritten constitution, and from a lengthy history of English common law that goes back through the Petition of Right, the writ of habeas corpus, going all the way back even to the Magna Carta.

So what then really took place is that the common law of England was our base – and in a sense, it still is. And we’ve extrapolated on that our own statutes. So we begin with a common law, and then the legislature goes to work, and it either affirms the common law by statute, or leaves it alone, or upends it and says, “Well, this is a common law rule, but we in New York are legislating or codifying something else that undoes the common law.” So that’s the historical trajectory, and we still function that way today.

Lauren: Well, when you’re 250 years old, you certainly have a long history of interesting cases that have been heard inside the walls. In order to get some of these highlights. We spoke with Noel Levee, who is the city of Johnstown historian.

Devin: What about the trial that involved Aaron Burr?

Noel: That’s an interesting one, and I had to read up a little bit more on to it. Solomon Southwick, who was a former speaker of the assembly for the state, he was the defendant, and the plaintiff was Alexander Sheldon, who was the current speaker of the assembly of the state. If you ever read the book on Hamilton, Hamilton tried to establish a federal bank for the country. That was one of his little things he wanted to start, and there was a lot of opponents for it. At this point in 1812, that came up again, to build this bank in New York City. Alexander Sheldon charged Southwick with bribery, because he claimed Southwick tried to get him to vote for the creation of the bank. Big, big trial. The defendant, for his attorneys, he had Abraham van Vechten, I think Alexander Foote, and Daniel Cady, and the high profile attorney leading it was Aaron Burr.

[Aaron Burr] had already had a lot of intrigue in his life at this point. In 1804, he had killed Alexander Hamilton [in a duel]. He was vice president under [Thomas] Jefferson. He was brought to trial for treason, because he tried to create his own country. And so that was what brought the crowds in. The courthouse was packed. The outside was packed, the whole grounds were all packed with people. The other attorneys asked some really pointed questions to Sheldon, to a point where he was sweating profusely on the stand. And they caught him with some off [statements], he had said some things that weren’t quite right. And this is what got him, I guess.

Devin: Burr won the case.

Noel: They won the case.

Lauren: So what about the trial of Elizabeth van Valkenburg?

Noel: That was very interesting. 1845. They were living in Perth, which is not far from here. She was married for the second time. Not a very nice guy. He drank a lot, and was abusive, I guess, to her kids. So she decided she was going to buy some arsenic. He came home after several days, and she gave him a cup of tea with [arsenic], and he evidently got violently sick. And then she actually had a bleeding heart and tried to nurse him back, and he didn’t drink for a while. And then several months later, he went back. So she just kept pouring the arsenic back in. And eventually, he went through a convulsion, and she got scared and left the house. She went to a neighbor’s barn and tried to hide out there. She was up in a loft, and she fell out of the loft and she broke her hip.

Well, I guess it was a fairly quick trial. Even the judge had said, “I don’t have any pity on you.” Although, she created an atmosphere in town where a lot of people were on her side, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They were both rooting for her and were against [the death penalty], because she did get the sentence of execution. They were against that. And then it came out toward the very end that she had been married once before, and it was pretty much the same situation, where it was the abusive drinking husband, and she did the same thing with arsenic and got rid of him.

Devin: One of the prominent judges associated with the courthouse is Daniel Cady, and obviously his daughter Elizabeth Cady Stanton. What can you tell us about Daniel Cady and what was their interest and role in the courthouse?

Noel: Judge Cady came to Johnstown. I think he was admitted to the bar in 1790-something, and he came to Johnstown shortly after that as a young attorney. As a practicing attorney, he also elevated himself to the New York Assembly, the Senate – actually, the year that Elizabeth was born, he was a United States senator for one year. Now, his house was always used for not only his family, but he also took in the interns, and he had a law library and all that. And of course, they would study. There’s that story – I mean, the interns were staying there through holidays. This was a Christmas morning. Young Elizabeth receives this necklace, and she shows it off, and actually, who she’s showing it off to is her future brother-in-law and his brother. And Edward Baird says, “You know, if you were my wife, that would belong to me.” And she goes, “Oh, no.”

Elizabeth got involved with the whole legal thing too because of her father. Again, there’s that other story that she tells throughout her life. In town here, there was a Mrs. Campbell. She had a grown son, and her husband had died. And the way the law was, the son inherited everything. She went to judge Cady to say, “Can’t the law at least give me a room in my own house that I can stay in?” And basically, he says, “The law all sides with your son, that he inherited everything and he gets it.” And Elizabeth tells a story that she was woeful that this woman was crying, and she says “I’m going to I’m going to go through my father’s law books. I’m going to go through every law that besmirches women, and I’m going to tear those pages out of the law books, so he can’t look at it.” The judge took Elizabeth aside and basically said, “Law books are printed all the time. If you want to change the law, you have to go to Albany or you have to go to Washington. You have to fight the change the law.”

Devin: One of the things that struck me in your research was how much the original courthouse was actually a community center.

Noel: Well, shortly after the Revolution, of course, Johnson built a coed interracial school, one of the first in the state, and that was kitty corner from here, on the corner. So anyways, after the Revolutionary War, the school was falling apart. And they started using the courthouse as a school. And in the meantime, they were building an academy, which was a tuition academy. And that’s where Elizabeth Cady Stanton went. And after the Revolution, one of the big things was the Fourth of July celebrations. After they started doing county fairs here. So they were using the inside of the courtroom, where they were setting up tables for fruits, vegetables, and whatever they planted. And according to one poster, the cattle and livestock were down the street a little bit and careened off.

Devin: It’s much different than the way we think of courthouses, and how they’re used today.

Noel: I mean, even up into recently, [before they] totally got strict with the laws about security, all you had to do was fill out a paper and you could use the courthouse, and there were functions going on here.

Lauren: There are so many fascinating stories in the history of this courthouse. But perhaps the most amazing feat is that today, in 2022, it’s still a functioning court. So what does it look like today, and how has it changed over the years?

Devin: As we mentioned earlier, we toured the courthouse and met with Judge Gerard McAuliffe, who spoke about the work of the court today.

Gerard: This court is utilized today, and every day, for hearing motions, trials, hearings of both civil and criminal matters. In fact, we recently had a presiding Supreme Court Justice named Richard Aulisi, who retired approximately three years ago, when he was the Fulton County Supreme Court Justice. He was assigned as the asbestos judge in that regard. He would, once a month, have what they called “Asbestos Day” in the Fulton County Courthouse, where 25 percent of the cases on his docket would be conferenced, with between 90 to 110 attorneys who would attend that conference day. Judge Aulisi did that for years, and our Fulton County Courthouse was utilized to conference effectively all the asbestos cases in upstate New York. The courthouse on a daily basis provides us an opportunity for those in the court system to have meetings, seminars if necessary. So, our courthouse is vigorously utilized today.

Devin: The courthouse’s exact birthday is September 8. And in honor of this, there is an elaborate celebration being planned. Possibly the most exciting aspect of which is that the New York State Court of Appeals, our state’s highest court, will be meeting at the Fulton County Courthouse instead of their usual chambers in Albany.

Lauren: One of the aspects of the celebration I think is really cool is that the event planners are working with local school districts to ensure that students are in involved in the celebration as well.

Gerard: When the Court of Appeals decided they would come to Fulton County, they asked one thing of us here: they asked us to engage our high school students in the process. We hope to have high school students seated in a preferred seating area, where they’ll be able to observe the arguments on September 8, 2022, from a vantage point that will be very, very unique. Those arguments will also be live streamed, and there’s also a very good possibility that we will have an overflow area outside, where arguments can be viewed remotely. We will have the courthouse available for tours and viewing throughout the remainder of that day.

This courthouse, to me, and the process that we have gone through, has been a shining beacon of hope for the people of our city, county, state, and nation. Today, as I said, it’s engaged in every aspect of civil and criminal litigation, and perhaps very importantly, for our discussion, in the midst of this pandemic, this courthouse has continued, giving us an opportunity here in Fulton County to focus on the positive nature of our history, to take a moment, to recollect where we’ve been, what we’ve done, and perhaps where we’re going. So the courthouse to me, speaks volumes. And it’s no less a shining beacon of hope today than it was 250 years ago, at the time it was built.

Lauren: As illustrated by those we spoke with, this courthouse evokes strong feelings from those who use it daily as part of legal proceedings and court cases, but also those in the community who have an appreciation for the 250 years of history it has not only witnessed but played an active role in. From the time when people living in Johnstown were British subjects, all the way to the present, this Court has been involved in delivering justice, as a community gathering space, as a place to celebrate, and to congregate. It remains active in the legal system today, and continues to bring feelings of reverence from those who sit inside its walls. The celebration that is planned for September 8 will be yet another piece of the puzzle in this building’s amazing history, and we encourage our listeners to be on the lookout for more information on the celebration as the date draws closer. And we wish the organizers the best of luck in this great event.

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.