In this episode, Devin and Lauren investigate the invasions of Canada by the Fenian Brotherhood, a group of Irish Nationalists intent of freeing Ireland from British control. These invasions were launched from several locations in upstate New York, including the site of a recently-erected William G. Pomeroy Foundation marker in the Franklin County town of Constable.

Marker: The Fenian Campsite, 16902 NY-30, Constable, NY, 12926

Guests: Lawrence E. Cline, author of Rebels on the Niagara: The Fenian Invasion of Niagara, 1866, and Martha Gardner, Town of Constable historian

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from The William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, and features music from Get Up Jack and Slainte. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

- Rebels on the Niagara: The Fenian Invasion of Canada, 1866, Lawrence Cline (2017)

- When the Irish Invaded Canada: The Incredible True Story of the Civil War Veterans Who Fought for Ireland’s Freedom, Christopher Klein (2019)

- Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion and the 1866 Battle That Made Canada, Peter Vronsky (2011)

- The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenians Raids, 1866-1870,Hereward Senior (1991)

Teaching Resources:

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute In History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. We’re so excited to share this new series of episodes and stories with you. And this time, we’re going about it a little differently. In the past, the William G. Pomeroy Foundation has been a funder for our podcasts, and a great partner to us. And so this season, we’re going to start off by focusing on one Pomeroy-funded historic marker for each episode. And the hope there is that we’ll be able to find lots of interesting topics that are scattered across the state of New York, and actually beyond that, because Pomeroy has lots of different programs that they use for their markers across the United States.

You know, one of the things, Devin, that I was thinking while you were talking, is about how accessible these markers are across the state. You can pretty much go into any community around where you live, or hours away from where you live. And that blue and gold symbol of the sign is so recognizable that you automatically know when you see it: something historically important happened here. When I was thinking about the markers, and why they are so important to not only the history community, but the community at large, is because they give you just enough to pique your interest. And if you find something that is interesting to you, you can go on and read more about it. It’s kind of like the hook that gets you involved in learning more about the story.

Devin: That’s exactly true with the markers and a little bit, I hope, with the podcast as well. We hope to do a little bit of a deeper dive than a historic marker can do. But of course, we’re not going to be able to touch on every aspect of every historical event that we take a look at with a podcast. So we’re going to have our website for each episode, which is going to include further readings, online resources, as Lauren mentioned, teachers’ aides, etc. – for those who want to learn more about these topics, who want to learn more about the stories that happen locally in New York state, and how they touch on so much else that’s happened nationally and internationally.

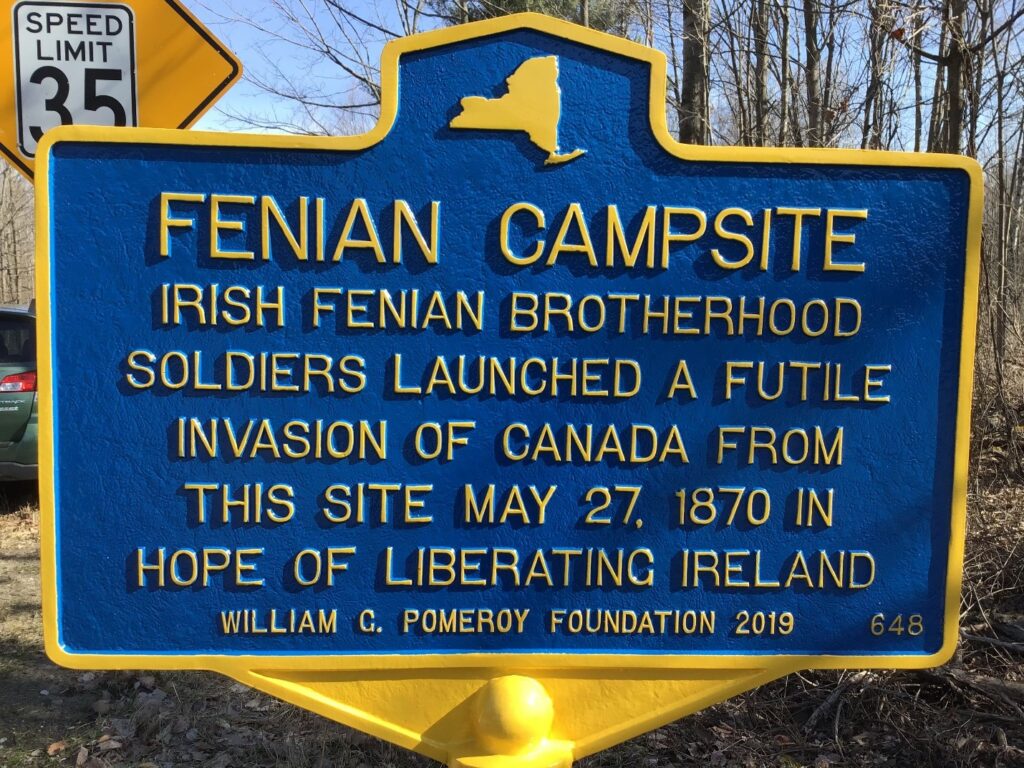

Lauren: So for our first episode featuring this format, we are focusing on a historic marker in Franklin County called “The Fenian Campsite.” And the text for this marker reads: “Irish Fenian Brotherhood soldiers launched a futile invasion of Canada from this site, May 27, 1870, in hope of liberating Ireland.”

Devin: Right, an invasion of Canada with the hopes of liberating Ireland that was based in New York. I, as state historian, knew nothing about the Fenian invasion of Canada, frankly. You know, one of the exciting things about being a historian is that you can’t possibly know all of history, especially about a place like New York, that has such varying levels and depths of history. So it’s exciting to come across something like this, where you say, “Okay, I don’t know much about this, or anything. I’m going to learn!” And what you learn is absolutely fascinating.

So first off, the Fenian Brotherhood actually invaded Canada twice. There is the 1870 invasion in Franklin County, but before that they launched a larger effort from Buffalo in 1866. To learn more about that, I called up [Buffalo State College] professor Dr. Lawrence Cline, who recently published a book on the subject called Rebels On the Niagara.

Dr. Cline: Perhaps somewhat peculiarly, in terms of writing a book like this, I’m not a historian. My training is in political science, actually. But along the lines, I kept running into the Fenians.

Devin: In Ireland in 1848, during the worst of the Irish famine, there was a rebellion by radical Republicans who wanted complete Irish rule. Called the Young Ireland Rebellion, this uprising was not successful – but it did set the scene for the creation of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Fenian Brotherhood in 1858. What’s different about the Fenian Brotherhood and the Irish Republican Brotherhood is that they’re a form of Irish nationalism called Republicanism, that attempted to free Ireland from British rule through, really, any means necessary. There were other groups that were seeking freedom through parliamentary means and through non-aggressive means, but the Republican Brotherhood and the Fenian Brotherhood were really interested in a more militant way forward.

I think one of the things that I learned in the book, and later on speaking with Professor Cline, was that the Fenian Brotherhood, which was a U.S.-based version of this group, was actually larger and more militant than the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Dr. Cline: Numbers, of course, in those days were variable. But there were probably only a few thousand, at most, members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. At its peak, there were probably something like 50,000 active members of Fenian Brotherhood itself.

Lauren: So Devin, why do you think it was bigger in the U.S. than it was in Ireland?

Devin: Well, that’s an interesting question, and it’s a question that we posed to Professor Cline. But one of the reasons is, of course, during the Irish famine of 1845-1849, there was a large influx of Irish immigrants to the United States, specifically to New York. Also elsewhere, they often entered New York, but then settled elsewhere – but a large proportion did settle in New York. And many of these people actually had to flee Ireland during the famine, because there was no work, there was no food, it was a real refugee crisis at the time. And many of these first- and second-generation Irish immigrants actually blamed the British for the famine, and for not reacting to the famine in a proper way to help them. So they felt that they were actually forced out of Ireland, the home country, to the United States because of the British.

Interestingly also, on the militant side of things – why were they more militant? Well, we have to remember, the first Fenian invasion of Canada was in 1866. But what happened from 1861-1865? The Civil War. Many of these Fenian Brotherhood members served in the Civil War – mostly on the Union Army side, but in some cases on the southern side as well. And almost all of their leaders were former officers. So these Fenian Brotherhood members were active military, I mean, they were in combat. So they were trained, they were hardened soldiers. They knew what they were doing. And they had this kind of affinity and passion for Ireland – coupled with a hatred of the British, who they blamed for the famine of 1845-1849.

Dr. Cline: I should note that, almost from the start of the movement, there were huge splits in it. It never was, really, a unified organization. There are at least two Fenian leadership groups, at some point, there were three of them. In some cases, it appeared that they really were sort of trying to use Canada as a bargaining chip between the U.S. and the British government – essentially to where, if they established even a foothold [in Canada], they [could] pressure the British to withdraw from Ireland. Obviously, that’s subject to considerable debate. I think in some ways, the rationale was we have to do something.

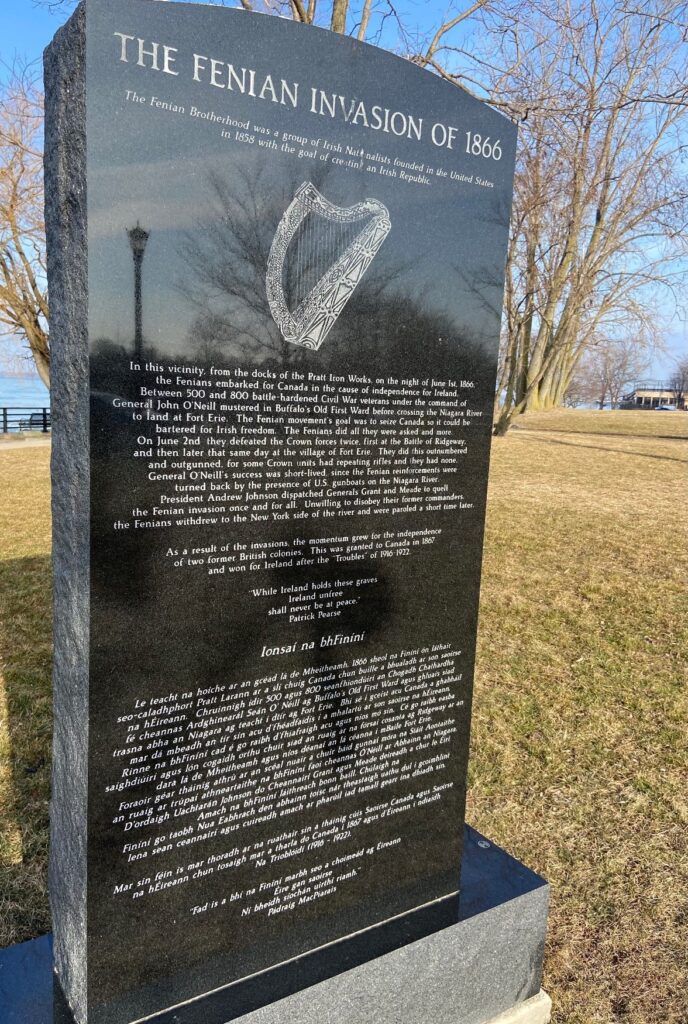

Devin: All of this brings us to 1866 and to Buffalo, New York. So Buffalo, for all of our listeners, we know where buffalo is – it’s on the Niagara River, across from Canada. And the Fenians were talking about this for years, and actually were very public about their plans to do this. In a way, it was how they were raising money [and] getting members. And so it shouldn’t have been a great surprise when hundreds of them, an estimated 800, showed up and set across the Niagara River into Canada.

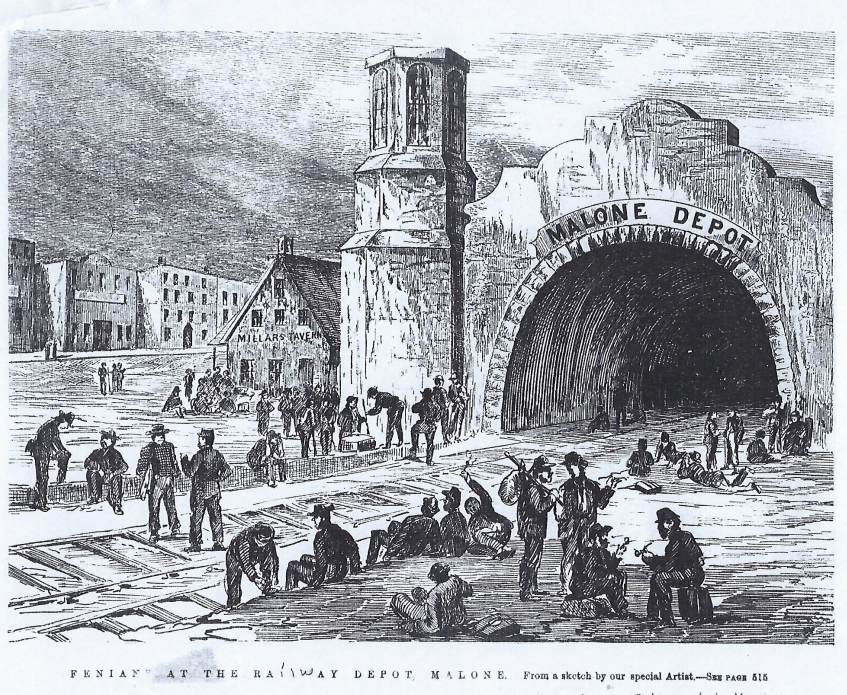

Dr. Cline: We still don’t really know what the direct objective was, it could have been the Welland Canal, which would have been logical, but they had this somewhat grandiose strategy, where they were going to have a three-pronged invasion of Canada. One to the east, up through the Malone, New York area and Vermont. One in the center, initially through Cleveland but then they changed it to Buffalo. And then the western portion probably going up through Detroit. Detroit/Chicago (because they were sort of back-and-forth on that) never took off, because the general never showed up, along with his troops.

On 1 June, the Fenians decided to cross the Niagara. They moved up the Niagara peninsula, and the Canadian forces, despite seemingly having good information that this was going to happen, were very surprised. They met at the Battle of Ridgeway, also known as Limestone Ridge on 2 June, 1866.

The Fenians were not particularly well-equipped, but the sad part was the Canadian militiamen were even worse equipped than the Fenians were. And more importantly, they had much worse leadership. The Fenians broke the Canadians, who fled in virtual terror from the field. The Canadians lost nine killed in action, with another 22 dying of wounds or disease. The Fenians, there’s a lot more question about that, but probably about nine were killed.

The night of 2 June, then, the Fenians, under General [John] O’Neill, moved into the old Fort Erie, the actual fort itself. And this is where I can sort of empathize with the commander, because it’s night, there’s been a battle, although it was successful – but you still lost troops. [You’re] tired, hungry, thirsty, and you don’t know what’s going on elsewhere. I can just picture the questioning going on: “OK, now what?” They knew there would be certainly more Canadian troops, and probably British troops, coming to face them. And around the campfire, you have to make the decision. And essentially what O’Neill decided to do was, “Let’s withdraw.”

Lauren: Interesting. So instead of going forward, they stopped, turned around, and went back to the U.S. without the Canadians pursuing them? They just decided on their own [that] they couldn’t hold the fort, there weren’t enough of them?

Devin: Yeah, they really didn’t have any intelligence about whether or not the other prongs of their attack were successful. They also were expecting more than 800, an estimated 800, Fenians taking part. So they kind of got to the point where they were like, “OK, we’re in Canada, what do we do?” And [they] made the decision that, rather than wait until the regular British military and Canadian militia surrounded the fort, they would head back across the river, which is what they did. So it was a success on one hand, in that they were successful in their first confrontation with the militia, and brushed them aside pretty easily. But again, there was no real plan. “What do we do? Where are we trying to go to take over Canada, or to at least threaten Canada in such a way that negotiations can begin with Ireland?” None of that was really planned out. And as a result, it fell apart.

One of the interesting things about the aftermath of the 1866 invasion of Canada is the kind of loose way that the Fenians were treated by the American government – who was somewhat embarrassed by the whole thing. In the aftermath, they did not come down hard in any way on the Fenians, including their leadership.

Dr. Cline: And there’s still debate about this among any number of historians, or people who’ve looked at it – as far as how much of a wink and a nod President [Andrew] Johnson had given the Fenians for invading Canada – but that becomes somewhat of a side note. They suddenly have all these people who they can’t really call prisoners of war. They’re almost the equivalent of illegal enemy combatants, using today’s phraseology. A few of the senior people they temporarily held, but they essentially let them get out on bail, and then quickly pardon them. The rest of the soldiers, they just said, “Here’s your train fare, go home.”

The other people who had some issues with this, of course, were the Canadians, because during the various wandering around in Canadian territory, the Canadians captured a little over 100 Fenians – and they had to decide what to do with them. Initially, they’re going, “Well, you’re illegal,” and they sentenced several of them to be hanged – which the U.S. government did not approve of, to put it mildly. And there were a whole lot of diplomatic communicators going back and forth, primarily between the U.S. and Britain because, of course, with Canada still being a colony – or the various Canadian provinces still being colonies – the U.S. did not want to deal with them, they dealt with the [British]. Eventually, all the prisoners that the Canadians held were pardoned, and the Canadians said the same thing: “Go home.” So that ended the “Great Invasion of 1866.”

Devin: Here’s what did happen in the years following. On July 1, 1867, you have the confederation of Canada. The British government passes the British North America, or Constitution, Act, uniting the colonies of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia into a single dominion. And in some ways, the Fenian invasion of 1866 could have played a role in that. Some historians do argue that the Fenians made the Canadians feel more vulnerable, and by uniting, they’d be better equipped to protect themselves.

At the same time, the Fenians continued to send supplies and people to fuel and lead rebellion efforts in Ireland. None of these efforts were particularly successful, however. In 1867, the Irish Republican Brotherhood was basically fighting with glorified spears, and it took about 48 hours for the British to shut them down. But no, the Fenians never really saw any punishment in the U.S. And as a result of that, it allowed the Fenians to kind of regroup over the years of 1866 to 1870, and do it again. And that’s how we end up with the 1870 invasion.

Lauren: So I spoke with Martha Gardner, who is the historian for the town of Constable. She’s been there for about 18 years, and she was actually the one who applied to the William G. Pomeroy Foundation for the grant to erect the Fenian campsite marker. And the reason she did that was because last year, 2020, was the 150th anniversary of the 1870 raid, which took place from Trout River.

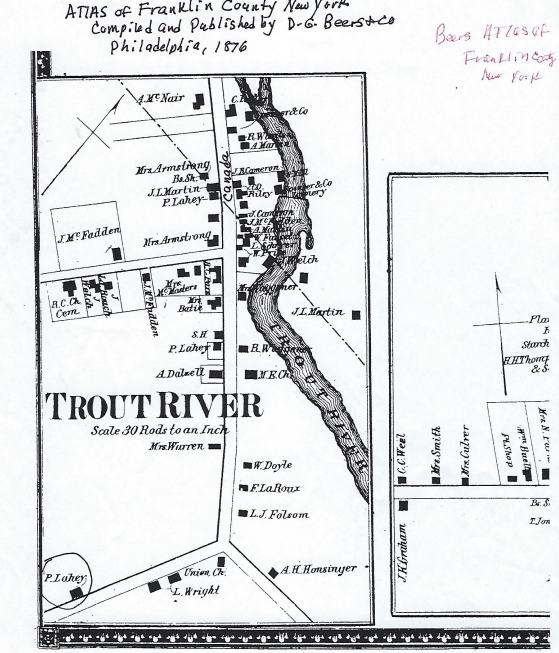

Devin, you just mentioned when you were speaking about the 1866 raid that it was supposed to be a three-pronged attack – and in fact, there was a raid from this area, the Malone area, in 1866. I asked Martha if the locals in Trout River – which is a very small hamlet, right on the Canadian border in Franklin County, it’s within the town of constable – I asked her if the locals of Trout River were supportive. Because now this is the second time they’ve been through a Fenian raid from their area.

Martha: I think it was sort of half-and-half. But you have to understand, there were many, many, many Irishmen here. First generation Irishman, people who had just come over. And so a lot of the people did feel that way. But a lot of the people did not – there was probably like maybe a half-and-half. But the people who were sympathetic to the cause were very quiet about it.

This time they were more secretive about it. They sent supplies and things on ahead, and hid them in different farms and businesses. They started arriving, and camped on the farm of Patrick Lahey, who swears that he had no idea that they were coming, and did not tell them they could camp there – but then how did they know where to go, as soon as they got here?

So anyway, they came, and there was a lot of back-and-forth, and there were soldiers…but no officers. They were coming in dribs and drabs. There would be like 100 people here, and then another two or three came, and then another two or three came, and sometimes there were big groups – but they didn’t want to come all at once and get everybody all upset. They also were supposed to be doing this the day after a raid in St. Albans, Vermont, that went awry. They got into Canada and were immediately repulsed, and the officers were arrested. So the backup they were supposed to get from that never happened.

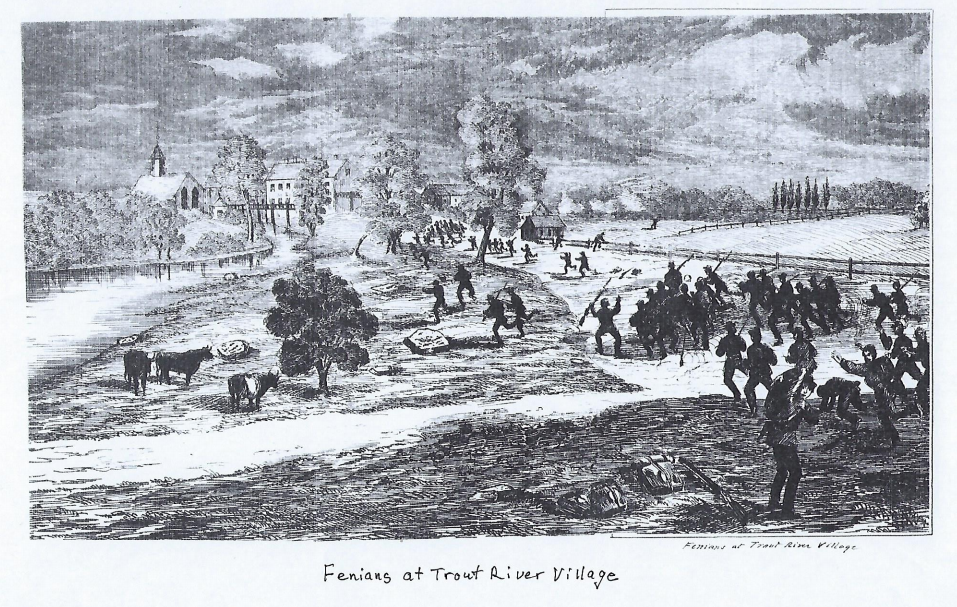

So you have these soldiers who are back and forth from Malone to Trout River – a lot of Indians, and no chiefs, telling anybody what to do. They were getting supplies, but that was coming slowly too. And some of them decided that they would go into Canada anyway. So they went across the lines, not very far, the first little store – and cut the telegraph lines and demanded food from the storekeeper. And they came back, and then another group went over and spent the night – but then a general finally arrived, went over and got them, and brought them back. I mean, it’s just…they really didn’t know what they were doing.

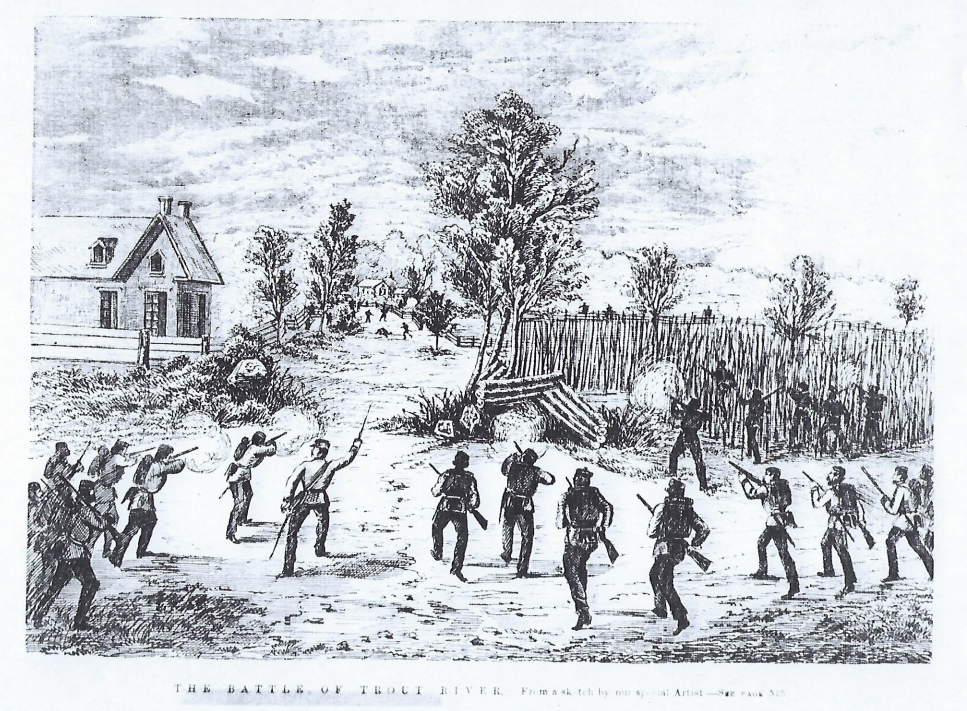

Lauren: So on the morning of May 27, [1870], there was a lot of debate about whether they should go forward with the raid. There was certainly a smaller number of Fenians than what they had expected. I think they were thinking in the thousands, and there were something like a few hundred that showed up. And there was some conversation about whether [they] should wait for more people to come, or should [they] go across while [they] have the element of surprise. They kind of ended the conversation without an answer, but a small group of maybe about 200 decided they were going, they were gung ho – “We’re going to cross the border.” And they did, they went ahead and they set up a breastworks as a defense for the Canadian militia.

So even though, this time, it had been more secretive, the British had spies all over the Fenian organization. So they knew that they were coming. Almost as soon as the breastworks were finished, the militia came. And the Fenians did fire a volley at the Canadian militia, but the Canadian militia kept advancing. And so there was a very brief skirmish of about 15 minutes, and the Fenians turned around and ran back across the border. As a result, there was one Fenian who was captured. A few of them were wounded. There are some conflicting reports about whether one Fenian was killed, but that was kind of the extent of it. There really weren’t any mass casualties, there were very few wounded. And it was kind of over before it began.

Devin, you mentioned before that the federal government under President Andrew Johnson actually provided train fare for the Fenians to return home in 1866. This time around, President Ulysses S. Grant had no interest in doing that. And there were several Fenians that didn’t have the money to get home. It turns out that the railroad agreed to give them half-price fares, and I think some of the locals took up a fund to be able to pay their train tickets to get them back home.

So this raid was even less successful than the one in 1866. I think there was kind of a fizzle out in general after the second raid. [There was this notion] that the government wasn’t really going to play along anymore, and that there needed to be an end to this.

Devin: I think you’re absolutely right, Lauren. And I actually asked Lawrence Cline that very question, and this is what he said.

Dr. Cline: Grant did not care much for the British, but he cared even less for the Fenians. So there was a lot of back-channel communications and cooperation going on. The other issue, of course, was the Fenian security was just unbelievably bad. At one point, in fact, their senior commander in Ireland was also a British agent. Many of their senior people were just providing information left and right to either the British or the Americans. And they knew they had security problems, but then that also added to the fracturing – because of a “If he’s my ally, he cannot be a spy” sort of thing.

I think in many ways – and I don’t want to trivialize the members, because many of them were true believers – but they were more aspirational than actually effective. By 1870, I think some of their best people said, ‘Look, I’ve got a family to raise.’ In several cases, both in 1866 and 1870, the Fenians going to war we’re going there singing Irish fight songs on the trains, and telling everybody they’re going off to beat the British, etc. And the federal marshals along the way just sort of said, “Why don’t you turn around and go home?” And they sort of went, “Oh, OK.”

Devin: The Fenians continued on after 1870. They continued on, really, up until 1876. And at that point, the Fenian Brotherhood really broke apart, and did not continue on in any relevant way in the US. But what was interesting to me is Professor Cline explaining that the term ‘Fenian’ lived on.

Dr. Cline: It was sort of ironic that their operations generally failed utterly, but they became sort of the myth of the Irish resistance – the term “Fenian.” For years afterwards, whenever there was a terrorist attack, or a small uprising here or there, the British press was always, “These are the Fenians.” The tradition of the Fenians sort of went on and became the catchphrase for many years for the Irish resistance – and probably, I would argue, until the rise of the Irish Republican Army itself.

Lauren: The Fenian campsite historical marker was erected earlier this spring at 1690 NY-30 in the town of Constable. I asked Martha why she felt it was important to erect this marker 150 years after the raid took place – a raid that was an epic failure, and at the time, damaged the relationship between residents of Trout River and their Canadian neighbors. And her answer reflects what Devin and I were saying earlier about this story largely being lost to history.

Martha: Very few people know about this. And that’s one reason that I wanted that marker put up. It’s like Constable’s claim to fame. But people need to know, that this is part of our history, and this happened. And I also did it for the Canadian people, because there was a lot of Canadian traffic back and forth through here. And so [they’ll] know that yeah, this is part of your story, too, as you’re going back and forth.

The couple that owned the property – I had to do a lot of looking, because shortly after all of this happened, Patrick Lahey sold a lot of his property, including where they had camped, and it’s been divided up and sold. And so I spent quite a bit of time in the tax map office, and figured that this is probably approximately where it was, right on the border between two properties. And the people who own this property now live in Montreal. This is a summer home for them. And they are both of Irish descent – I just thought that was so funny.

Devin: Thanks for joining us on this episode of A New York Minute In History. This Podcast is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC Northeast Public Radio, and Archivists Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy foundation.

Lauren: We’d like to thank author Dr. Lawrence Cline and Town of Constable Historian Martha Gardner for their time and expertise.

Devin: A big thanks to the band Get Up Jack, and the Linda, WAMC’s performing arts studio, for providing some of our music. Our producer is Jesse King.

Lauren: You can find this episode, pictures, and more information about the Fenians at wamcpodcasts.org. Join us for the next episode, when we remember one of the country’s first supermodels. Until then, I’m Lauren Roberts.

Devin: And I’m Devin Lander.