On this episode, hosts Devin and Lauren delve into the history of Albany County’s Rapp Road Community, an African American neighborhood built by southern immigrants who moved north for a better life in the late 1920s.

Marker of Focus: Rapp Road Community Historic District, Albany County

Guests: Stephanie Woodard, board member of the Rapp Road Historical Association; Dr. Jennifer Lemak, chief curator of the history collection at the New York State Museum, and author of Southern Life, Northern City: The History of Albany’s Rapp Road Community

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further reading:

Southern Life, Northern City: The History of Albany’s Rapp Road Community Jennifer A. Lemak (2008)

Black Protest and the Great Migration: A Brief History with DocumentsEric Arnesen (2002)

The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed AmericaJames N. Gregory (2005)

Teacher Resources:

PBS Teaching Guide: Exploring the Great Migration

National Archives- Harry S. Truman Library and Museum: The Great Migration Lesson Plan

Stanford University, Stanford History Education Group: Great Migration

National Geographic: The Great Migration- Educator Guide

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

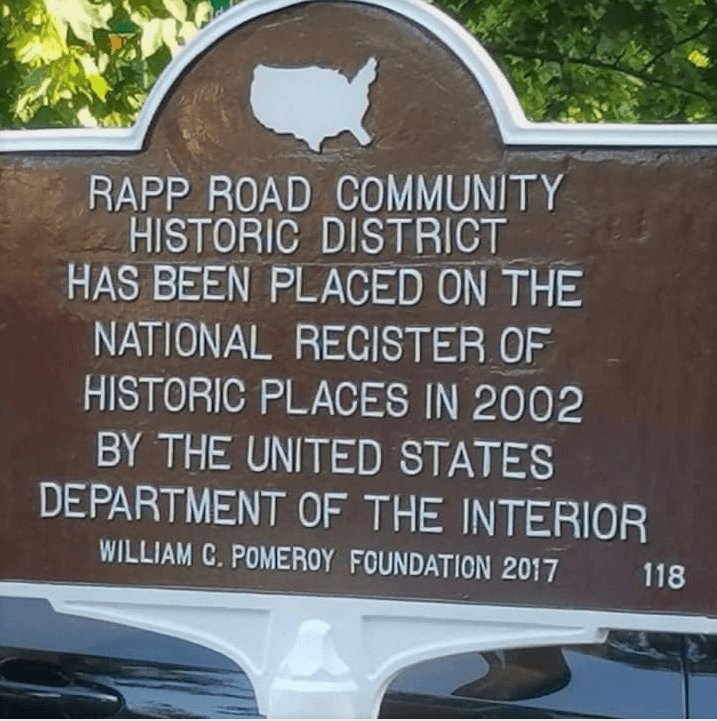

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. This episode is focusing on a marker which recognizes the history of a small African American community located within the city of Albany that came into existence as a direct result of the Great Migration. Now, this sign isn’t a traditional blue-and-yellow historical marker. It is brown, and has white text on it, and it recognizes the inclusion of this community on the National Register of Historic Places. Located at 28 Rapp Road in the city of Albany, the text reads: “Rapp Road Community Historic District has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002 by the United States Department of the Interior. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2017.”

The marker we’re focusing on today is part of a different grant program offered by the Pomeroy Foundation. When a structure or a district receives that designation, there’s no allowance of any kind for signage or a plaque, so the Pomeroy Foundation offers a program where you can apply to them for a marker, in order to increase awareness of the historic place.

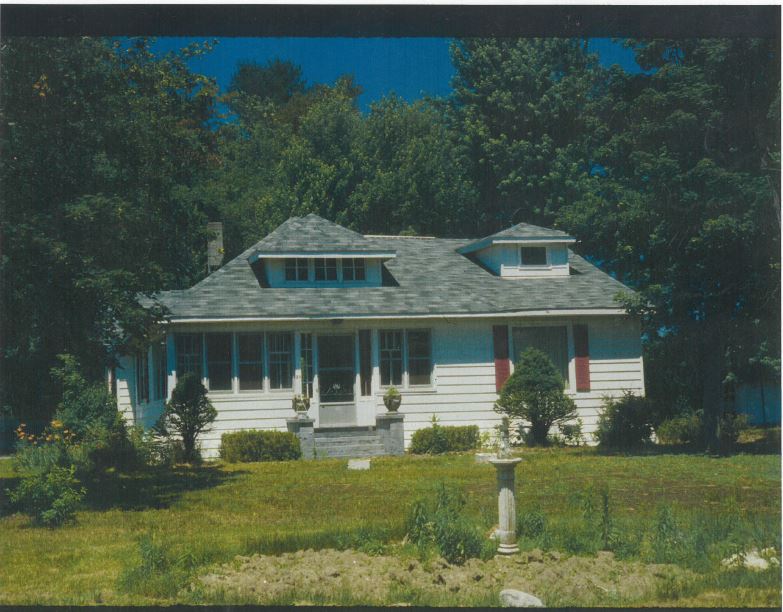

Getting back to the Rapp Road Community Historic District – as far as the location, it’s located near Crossgates Mall. So it’s near a lot of heavy commercial development today, but that wasn’t the case back in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when the community was formed. The houses here have a different look than the rest of the nearby neighborhoods, and the general residential areas around it. So how, Devin, did the Rapp Road community get its start, and where did the founders of this community come from?

Devin: The genesis of the story begins in the Deep South. The vast majority of the residents that would go on to live at Rapp Road here in Albany came from a town called Shubuta, Mississippi. Shubuta, Mississippi is located in eastern Mississippi, formerly on the lands of the Choctaw Nation, which were open to settler colonists during the period of Indian removal in the 1830s. Shubuta developed a role as a trading post and market for the surrounding cotton plantations during the antebellum period, and the vast majority of African Americans living in and around the area were enslaved. In 1865, the town of Shubuta was incorporated, and in the post-Civil War years, slavery was replaced with the almost equally oppressive sharecropper system. Racism ruled the day during this era of Jim Crow in the South, and Blacks lacked opportunities for education and good-paying jobs. Almost everything was segregated, and even walking on the wrong side of the street in Mississippi could get a Black person lynched. This horrific racial terrorism, along with the disenfranchisement of Blacks by the state of Mississippi, and the rest of the Deep South, led many to flee the area for a better life and better opportunities. This mass movement of Blacks towards an opportunity for a better life was called the Great Migration.

Jennifer: Between 1910 and roughly 1970, over 7 million African Americans moved from the southern United States to the north and to the west – predominantly cities, but a lot of African Americans also moved to rural areas.

Devin: We spoke Dr. Jennifer Lemak, chief curator of the history collection at the New York State Museum.

Jennifer: Out of the 7 million African Americans that moved out of the South, 1.5 million of these African Americans moved to New York state. The majority of them moved to New York City because of the lure of Harlem, but thousands upon thousands moved all across New York state: to the Hudson Valley, because brickyards in the Hudson Valley were some of the first integrated places along the corridor; to Albany, Syracuse, Rochester and Buffalo. There were lots of opportunities for employment, particularly during World War I and World War II, because factories had high manufacturing rates, and they needed people to come and fill these jobs. Places like Albany, they had huge increases, particularly around the wars, but also between 1950-1960. We see, you know, thousands upon thousands, the African American population almost doubling. A lot of people consider the Great Migration kind of being over after World War II, but there was a steady stream of migrants coming all the way through 1970.

Devin: The main force behind the settlement of Rapp Road was really Reverend Louis W. Parson and his wife Frances. Now, this is a very interesting story. They were both from Shubuta. They both left, originally trying to settle in Ohio, and things didn’t work out there for them. And one day, the reverend looked to his wife and said, “Let’s leave.” And they got in their car, and they drove – and they had no real idea where they were going, they just drove. And eventually they made their way into Albany, and they happened to be driving down Franklin Street when they noticed four women outside of a small church who were conducting a prayer meeting. And the Parsons stopped, and got out, and spoke to the women, and introduced themselves, and mentioned that he was a reverend. And the women said, “Oh, it’s interesting that you stopped by now, because our church is trying to find a new reverend.” And throughout the rest of his life, when asked, “Why did you settle in Albany? What brought you to Albany?” his answer was, “God led me to Albany.” And that congregation was the First Church of God in Christ, which was established in Albany and is still here.

After founding their church, the Parsons returned to Shubuta to recruit residents there to come north and join them. We spoke with Stephanie Woodard from the Rapp Road Historical Association.

Stephanie: We have to think this is [the] Jim Crow [period], there was still lynchings in Mississippi. The people who left out of Shubuta were sharecroppers, so their parents would have been slaves. Some stayed in Mississippi after emancipation and became sharecroppers. So when they made the decision to leave to go to Albany, you know, it was a significant decision, because leaving a debt in Mississippi was a crime. And you could get killed for leaving that debt. So when Elder Parson would come, people who wanted to come to Albany, they just had to be ready. First come, first serve, you get in the car, he would take you up to Albany. They would leave at night, and they will leave on a Saturday night, because the sharecroppers were very religious people in the South. These people were very religious, so no work ever happened on Sunday. So if they left in the night, they could get to the Mason Dixon Line before day, [and] all day Sunday, no one would think anything, because there’s no work being done on Sunday. Come Monday, they would be pretty much in Albany. So they would drive all night, and all day, until they came to Albany. They brought very little, maybe a suitcase, very little money, you know, maybe $1.75, or something to that effect.

And so this went on for a very long time, until Elder Parson was being threatened to be arrested. And when that happened, Jack Johnson – that’s my grandmother’s first cousin – he also helped. And he would come at night, I think he would honk the horn or do his light, and that meant first come, first serve, you get in the car. And it continued, it continued for several years, and that’s how people came up to Albany. They couldn’t take the train. Some people did take the train if they had the funds, but even taking the train was dangerous, because that was segregated as well. If a sharecropper knew the people who were operating train, you know, taking tickets and so forth, they could go down and say “Hey, if you see so-and-so getting on this train, call me, because they’re trying to get out of the South, and go north.” And even driving through the different towns is very dangerous. You can’t just stop wherever you want to stop and get food and go to the bathroom and get gas, you know, you had to have a specific area where you want to stop and get gas. So The Green Book, if anyone’s ever seen the movie, is true to fact. People of color had to be very, very, very careful. And then, not everybody could come, it was a decision of who’s going to go north, and who’s going to stay here. And if you are going to stay, where are you gonna go? Because you can’t live in the same house, where the sharecropper comes to get you and say, “You owe a debt.” So even though we talk about this all happening during the ‘40s, it’s very, very scary situation for them, and families were split up. But they all came together once they got settled in Albany.

I am actually a third generation of relatives who live out in Rapp Road. My grandparents, George and Dora Woodard came to Albany by Shubuta Mississippi and Mobile, Alabama. I would say it had to be in the ‘30s given my father’s age. They came here because their cousins had settled here, and they were looking for a better educational system. Back in Shubuta, Mississippi, when my aunt got to high school, around high-school-age(ish) – they didn’t have a high school, and they had to go to a different county. I believe that’s when my grandparents, particularly my grandmother, started looking at other states. So my grandfather had siblings in Alabama, and attended a Catholic school. But she still felt that there was a lot of segregation, and that they weren’t getting the best education. So that’s when they decided to move to Albany.

Once people started coming into Albany, they were living in the South End of Albany and [there was] a lot of crime, prostitution, gambling, and people wanted to go someplace else. And what Reverand Parson did was he also purchased land out where we now call Rapp Road. He would lend money, and allow people to purchase their land out there on Rapp Road, and they began to build their homes by hand. So they would come in the evening, after work or on Saturday, and build, and live in the South End of Albany until the property was complete. Other people out on Rapp Road would help, and some people came with a lot of skill. Like the McCann’s came with the skill of masonry. Other families came with other types of skills. So when they came out of the South, no matter where they came from, they did bring a lot of skill with them. And that’s why their property is still standing today, because they were able to use materials in order to create their homes and build their homes.

Lauren: The area of Rapp Road was much more like Shubuta than the South End of Albany, so it actually became a much better fit. They were able to practice gardening, they were able to carry on farming there. They talk about hunting. They had their own smokehouse, they would smoke their own meats. So it was important, I think, to those people coming up from Shubuta to have some continuity in their lives. Some of the things that they had done while they were living in Shubuta, they could continue to carry on while they were living in the north.

Devin: I think that’s a great point, Lauren. The South End was an urban environment, and these were rural people. And they were looking for something more akin to the lands that they came from, where they could own their own land, and farm, and grow their own produce, and hunt, and things like that. But I think one of the things we really need to remember too, is although Albany and the north during this time was much less dangerous, there was still overt and institutional racism that took place. And we get the sense from the history of the community that one of the reasons they wanted to move out of the city was to be among themselves.

Jennifer: At least from my perspective, from talking to folks, life on Rap Road was pretty happy when they were on Rapp Road. The folks that lived out there were really in a close community, and there was not much around them – the Pine Bush was around, there were a few farms out that way, but the only folks that went out there, for the most part, were the ones that lived there, or if you were visiting family that lived there. I would guess that most of the challenges came when the community left Rapp Road and went into the city of Albany, and they would face discrimination in parts of their daily lives. But Elder Parson and Elder Johnson helped folks get jobs, got their kids into the right schools, and for the most part, they all became members of their specific congregations. Being on Rapp Road was such a special place, so up until a certain point, I think it was really, you know, they’ve called it the promised land.

Stephanie: It’s a place where my grandmother went a lot, and the name “promised land” is exactly what it was. There was no traffic, you know, you just run around and play and, you know, people just got along to help one another. Everything was communal. There was a prayer house out there, so sometimes they didn’t even have to come into Albany to do their daily prayer or their weekly prayer. Jennifer’s correct, it wasn’t until you went into Albany [that they experienced racism]. You know, [Albany citizens] weren’t too receiving of all these African American people coming from the South, like it would be a burden on the Albany economy. And also it became dicey once Washington Ave Extension was built, because no one really even knew people even lived out on that area of Washington Ave. We did have an incident where the children couldn’t get to school, which would have been, I think, a school on Western Avenue. The Albany public school system would not provide bus transportation, because they said the road was too narrow to get the bus down Rapp Road and over to Western Avenue. So Wilborn Temple First Church of God in Christ purchased the bus to get the children to school. But other than that, exactly what Jennifer said. And I have recollections more of Shubuta, because my grandmother and grandfather used to take us down to Shubuta. And so when I got older, and started coming to the family reunions, like in high school, I remembered Shubuta, Mississippi, and the community was exactly the same. Everyone knew each other, had their own land or property. And as kids, there was no traffic. So we used to play and have a great time. And I just want to give a shout out to Jennifer, because she, too, has been to Shubuta. Right, Jennifer?

Jennifer: Yes, I have. One of the folks that I interviewed said that, you know, “God led Elder Parson to Albany.” And when you’re out there, and you realize how similar Rapp Road looks to Shubuta, Mississippi – there are pine trees down in Shubuta, and kind of sandy soil, and that’s very similar to what’s out in the Pine Bush. You know, it’s kind of otherworldly, that you’re like, “How on earth did this happen?” You know, there’s a connection.

Lauren: When they were welcomed into the community, these [other community] members had already been in their position, so they were more willing to help with food and shelter and getting a job. And it was almost like a communal living environment where they were helping each other out of a shared common past –

Devin: – that has its roots in Shubuta, for the most part. There were some folks who settled there who were not from Shubuta, but really the majority were from Shubuta, Mississippi, so they all knew each other, or at least knew of each other. You have to remember, Shubuta is a very small town. Today’s population is about 650, I think back in the 1920s, it was maybe around 1,000. So it was never a big metropolis. It was truly a rural place [where] the families would have known each other, that people would have known each other. So, again, they have this deep-rooted community and network that really helped establish Rapp Road as a separate community within the boundaries of the city.

Lauren: According to the national register nomination, between 1942 and 1963, 23 African American families bought tracts of land from Parson’s original land purchases. Today, approximately six families with connections to the original landowners still live there today. I guess that leads us into today. What is the community life like now?

Devin: Now, one of the things we realized as we look at the history of Rapp Road, is that this kind of idyllic situation has been under threat – and continues to be under threat. Not so much by horrors of lynching or the Ku Klux Klan, but really by some of the commercial development that [Lauren] mentioned springing up around Rapp Road as the city boundaries expanded, and as the suburbs expanded. One of the things that really put pressure on Rapp Road was the Washington Avenue Extension that was built. And you mentioned Crossgates Mall, which was a major building project, and was really the pressure that [prompted] the Rapp Road Historical Association [to come into being]. And that’s why they looked to place Rapp Road on the national register.

Jennifer: Getting the Rapp Road Community on the state and national register was particularly important for the community members out there, and specifically for Emma Dickson, who was worried that the Pyramid-Crossgates Corporation would come in and kind of take over the community. Starting in the 1990s, there was a plan to double the Crossgates Mall. They started buying up little pieces of Rapp Road property that came up for sale, even if they were between houses or between different lots. The fear of the community was that Crossgates was going to come in and ultimately connect all of those pieces of land – and out goes the Rapp Road folks and in comes roads leading into the mall, or out of the mall, or drainage, or whatever. So that is where I came in to the story. I needed to do a research project for a history class at the University of Albany, and Emma Dickson needed somebody to write the historic significance statement for the state register nomination. And it was kismet that we met and started working together. And so my initial research paper was a significance statement for the state board review.

Rapp Road was put on the state register in 2002, and then I think it went to the national register in 2003. The big deal with Rapp Road is that when it was designated it was still there. There have been other examples of Great Migration communities in New York state, not necessarily one that was originally rural, like Rapp Road, but neighborhoods in larger cities like Rochester and Buffalo, and even Harlem. But the fact that the community was still intact – is still intact, for the most part – [was significant]. It was unusual for African Americans to own property and own their own homes for most of the 20th century. The designation allows for some protections from outside development interests, and it allows for tax credits, if you do work on your home. From a private owner standpoint, a private homeowner can do absolutely anything they want with their home, even if it is part of a historic district.

I think it’s important for everybody to realize that there are still families out on Rapp Road, and the work of the Rapp Road historical society is never ending, because of the sheer proximity of where the community is, in the middle of a lot of development. And I gotta give a lot of credit to Stephanie and her colleague, Beverley Bardequez, who has been tirelessly working to continue to document the history of the community, and kind of protect it from all of those outside interests in development. And they are both so committed to keeping Rapp Road intact, and keeping the history alive.

Stephanie: The Rapp Road Historical Association, we work on behalf of the Rapp Road Historical District. We provide support. These are very private families, and they are strong-willed and want to keep their homes, so they need help. We try to provide the help that we can. And then we of course, we work with people like Jennifer Lemak, like “Hey, what do we need to do? Can you help us, and to provide us with guidance?” Along the road, we’ve met different architects, historic architects who are always willing to help us. We also speak on behalf of the historical district, like now, when we’ve had the change with Crossgates Mall and Costco and the apartments – and we’re involved in that whole process of approval. We’re really at the beck and call of the community in terms of what they want.

Every year we look forward to two family reunions. One with the McCalls, which is done on Orange Street in Albany, and the other was coming to Rapp Road. And we would have so much fun. We would always tell our friends, “You know, they shut down the street, when we have our family reunions, they shut it down.” It’s just, it’s always a place to learn more about your family, and who your family is.

Devin: Putting a community like that on the National Register of Historic Places was a complex endeavor. We have to remember that during the early 2000s, and before, many of the properties that were placed on the national register were attractive houses, historically important because they were the site of something to do with a Founding Father or some other community leader. They weren’t necessarily an essentially working class neighborhood. I think, also, it’s important, as Stephanie Woodard noted, that even if the families aren’t there anymore, many of the original houses are there. And these houses were hand built. These people were skilled.

Lauren: And although it’s a smaller number of families, it seems like the feeling of community still exists. The fact that they’re still holding family reunions today speaks to the fact that they’re hanging on to their heritage, and trying to continue the legacy of the original people from Shubuta, Mississippi who came here to try to make their own community and make a better life for themselves.

Stephanie: I tell my friends, when you’re coming out of Crossgates, you know, just take a slow ride through the Rapp Road. You know, just a nice little ride, and think about the history. Think about their families, think about where people came from. Think about how it’s so important to preserve natural history, and how important it is to preserve African American history, because there’s not a lot of national designations related to African American history. And we are so unique, that the designation was not about a pretty building. It’s really about people who came from the South at a dire need, and said, “I’m going to go to Albany, New York and build a better life, not only for myself, but also for my family, and for my legacy.” And when I ride through Rapp Road, that’s what I think about all the time – what we’ve been through, and how far we’ve come to this one community, just this one particular community.

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.