On this episode, Devin and Lauren tell the recently declassified story of a covert radio station built by the FBI on Long Island to deceive the Nazis during World War II. From 1942-1945, double agents worked in secret from a remote home in Suffolk County on the major operations “Bodyguard” and “Bluebird,” and dug up information that some believe contributed to the United States’ development of the atomic bomb. After the war, the Wading River Radio Station was taken apart by the FBI, but the house itself (then called “Owen Place,” but now known as the “Benson House”) is open to visitors at Camp DeWolfe. The property was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

Marker of Focus: Wading River Radio Station, Wading River, Suffolk County

Guests: Dr. Raymond J. Batvinis, former supervisory special agent for the FBI now with the Institute of World Politics; Rev. Matthew Tees, executive director of Camp DeWolfe

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Raymond J. Batvinis, Hoover’s Secret War Against Axis Spies: FBI Counterespionage During World War II

Raymond J. Batvinis, The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence

Neil Kagan, The Secret History of World War II: Spies, Code Breakers, and Covert Operations

Joshua Levine, Operation Fortitude: The True Story of the Key Spy Operation of WWII that Saved D-Day

Teaching Resources:

International Spy Museum, Educator Resources

The National Law Enforcement Museum, Virtual Classes

The National WWII Museum, Educator Resources

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On this episode, our marker of focus is not one of the blue-and-yellow New York state Historic markers that we usually talk about. The marker is brown and white, and it’s part of another marker program that the William G. Pomeroy Foundation offers called the “National Register Signage Grant Program.” This program offers a historic marker to individual properties or districts that have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This idea came out of the observation that once a property is listed, there is no provision for signage to acknowledge that accomplishment. So Pomeroy’s National Register Signage Grant Program looks to fill that gap so that these sites get the deserved recognition.

The marker we’re speaking about today is located at 408 North Side Road in Wading River, Suffolk County, out on the North shore of Long Island, on property that is now part of Camp DeWolfe. And the text reads: “Wading River Radio Station has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018 by the United States Department of Interior. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2018.” So what is the story behind the Wading River Radio Station?

Devin: It’s really a fascinating story. And it’s not the type of radio station that we think of today, that’s playing music or talk radio or something like that. It’s really a story of espionage, specifically counter espionage against the Nazis during World War II. Now, we’ve all heard of the Culper spy ring on Long Island – but I was surprised to learn that Long Island played such a significant role in the FBI’s efforts during World War II, specifically in two major places: one of which was in the early 1940s in Centerport, which we’ll get into in a minute, and the second that we’re talking about mostly today, the Wading River Radio Station, which still exists, the building is still there. As Lauren said, it’s part of Camp DeWolfe, which is owned by the Episcopal Diocese of Long Island, and operates as a youth and summer camp. In fact, you can go and stay at the house that the radio station was part of.

Matt: So my name is Reverend Matthew Tees. I’m the executive director of Camp DeWolfe. The Diocese has been around for just about 125 years and Camp DeWolfe has been an organization and mission of the Diocese since 1947. So right after World War II, we started our first year of summer camp. The information that we have about the house, it was originally built, we believe, in 1912. And the story is that it was a sea captain’s retirement home, because it’s basically right on the Long Island Sound, looking straight across to New Haven – so the widest part of the sound. And at some point, it transferred over to the Owen family. We traced it back online: basically, the family was in New York City in the late 1800s, and like many people they were looking for a house on Long Island to spend vacation time in. And so at some point in the early, I’m gonna say, 1920s and 30s, they purchased the property. Mr. Owens, well, he passed away. His daughter inherited the property, and she never married and she ends up passing away, so it actually went to her sister. And in the 1940s, basically, there was this property that the Owen family held, but they weren’t really using. And that’s when the FBI approached them to potentially rent out the facility.

Ray: The story really should begin with a case called the Duquesne Case that started for the FBI in February of 1940.

Lauren: To begin the story, we have to bring ourselves back to the World War II era. And just as a quick refresher: Germany invaded Poland in September of 1939, and that’s what officially started World War II. Now, America does not get involved in the war until after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941. So the story starts a little bit prior to our involvement. Just because we weren’t actively engaged in the war does not mean that we were sitting back on our laurels and just watching things happen. It was pretty apparent this was going to be another war that engulfed the entire world, so the FBI was certainly watching and getting ourselves ready for when we were going to be actively involved in the war.

Devin: It came to the attention of the FBI that there was a double agent within their midst, a man named William Gottlieb Seybold, who was an American citizen, but had immigrated to the United States from Germany. And upon returning home to visit his family, he was taken captive by the German Secret Service or secret police, and essentially forced into becoming an agent for them. They basically said, “You can’t leave Germany, and we’ll harm your family if you don’t do what we say.” So they trained him to be a spy, to broadcast over radio information about the preparation that the United States may be making for World War II – the supplies that they may be thinking about sending to the British, you know, just their plans in general. He was sent to New York to essentially begin his activities. But instead, he contacted the FBI. He was not a Nazi. He was not sympathetic to the German cause. And he said that he would spy on behalf of the FBI. So he became a double agent.

Ray: The FBI set up a radio station in Centerport, New York, which is very close to Huntington, it’s a tiny little hamlet. By May of 1940, they made contact with the Germans in Hamburg. And of course, the Germans felt that they were communicating with William Seybold.

Devin: We spoke with Dr. Raymond Batvinis, who not only is a former FBI agent himself, but he’s also a historian.

Ray: There’s a lot more to the story, but I think what we’re focusing on right now is the radio communication. And we learned a great deal [from this case] – we meaning the FBI and the United States government – we learned a great deal. It was a truly a classroom, a master class, for learning the art and craft and science of counter-espionage.

Devin: Because of the efforts of these agents and William Seybold himself, they were able to unearth over 30 German spies and bring them to trial, which essentially crippled the spy network that Germany had in the United States up until that time. Which brings us to Wading River.

Lauren: Right. So by this point, they know how effective the radio communication can be. So it made sense that they would try to set up a new radio station if they could find a similar situation with another double agent.

Devin: And that’s really what happened. The Nazis were trying to rebuild their spy network, and so they found a gentleman named Jorge Moscara, who was actually from Argentina, but had an import-export business in Germany. And they basically approached him and demanded – again, they weren’t asking – that he become a spy, because he had a network in the United States through his business in South America. So he could kind of travel back and forth and not be very obvious. And they also believed that he was sympathetic to their cause. Again, in the similar manner, they trained him to broadcast, via radio, information that would be sensitive to the war effort of the United States. And this was after 1941, this would have been after Pearl Harbor. So the Nazis were very interested in learning what the United States was doing, what they were planning, where things were going. Same thing happens, though, with Moscara. He tells the FBI, “I want to be a double agent.”

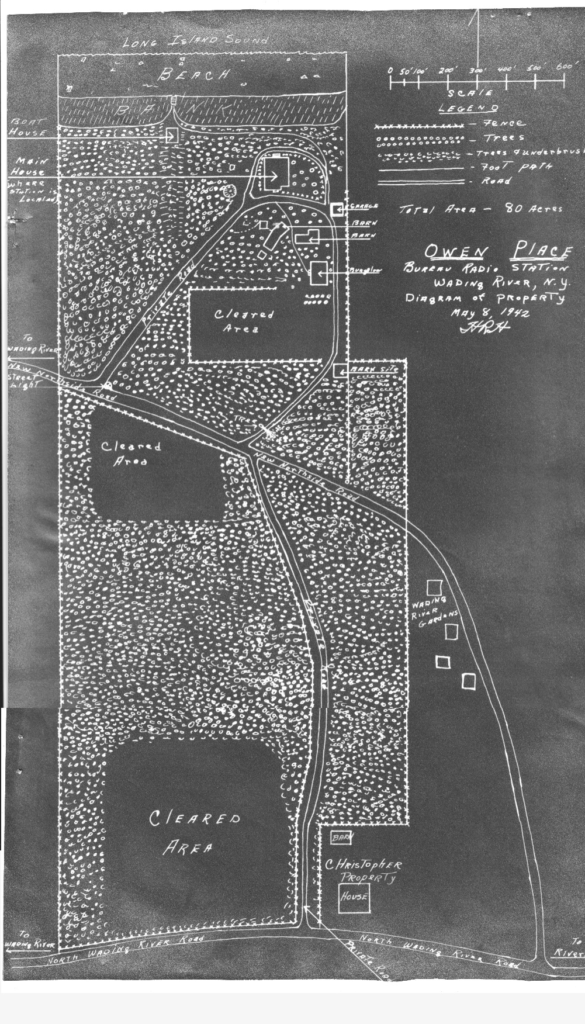

Ray: His codename was simply “ND,” like Nicolas David: “ND 98.” So, he came under the umbrella of the FBI, he explained to them what had happened, and that he had to set up a radio station. So that’s what they did. And they, again, set it up out on Long Island, only this time, they went further out.

Devin: The FBI, led by an agent named Richard Millen, who was an expert in radio technology – he was an FBI agent, but he was also an expert in radio technology – he chooses the house in Wading River, which is at the end of a long driveway. It wasn’t visible from any kind of major road or anything, it was secluded. But it was also very close to the shoreline. If you put in a radio tower, then you could reach Germany.

Lauren: One of the reasons that New York and Long Island in particular was such an important place for the FBI is because of the proximity to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. New York was really a hub not only of intelligence, but also of industry. And so it made sense, that Moscara would be able to collect information by going into New York City, being in close proximity to the Navy Yard where they could see who was going in and out, and what were the industrial products that they were producing.

Devin: For Millen, it was essentially perfect. And they set up a cover story.

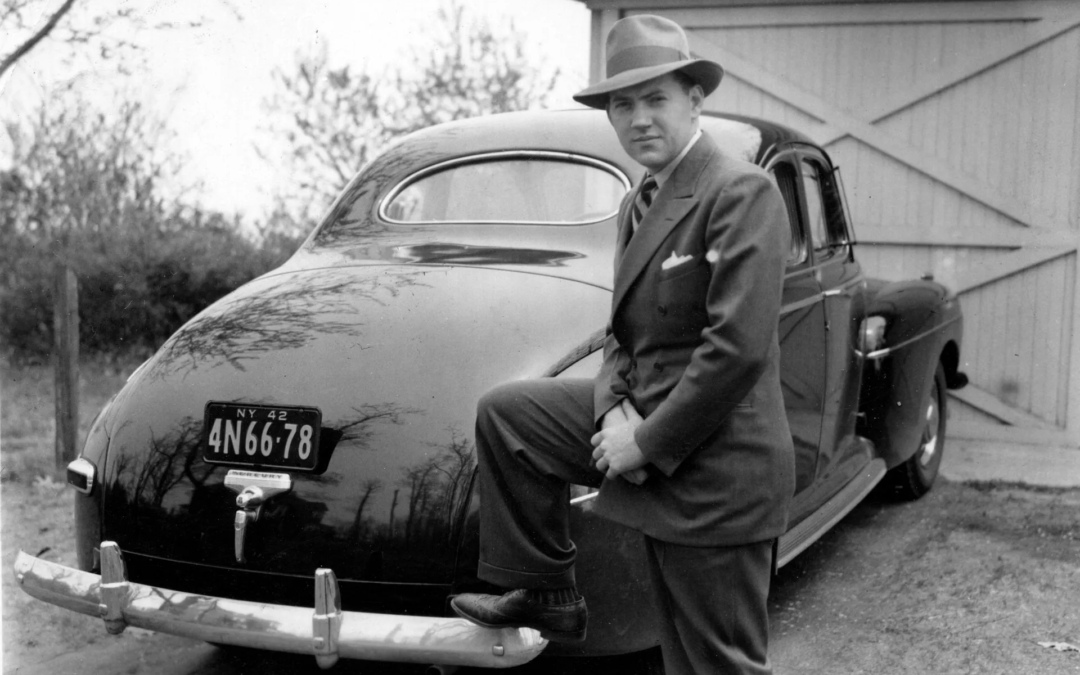

Ray: The cover story was interesting. They put an agent in there, and he had been a radio man in the Navy. So he had those technical skills. He had a wife, and he had a very, very young child. The child was a toddler. The cover story was that he had tuberculosis. The purpose of the tuberculosis story was specifically designed to keep people away. Tuberculosis at that time was a scourge, it was much like polio, and people feared it terribly. So the story that was put out was that he had tuberculosis, that he was actually a lawyer or something like that, that he had money, and that they rented the house. And he needed this for the fresh air to recover. So that was the cover story that they used, and it worked very effectively throughout the war.

Devin (to Ray): Yeah. And we know that there were other agents there as well, and they were completely clandestine. They weren’t even allowed, necessarily, to leave the property. So how would they have accomplished doing that for so long? For three years, essentially?

Ray: Yeah, that was a real problem. They had, we believe, about three or four or five radio technicians and agents working out there and living there on the property. The reason for that was Moscara was not the only double agent here in the United States that we were operating. We had about three or four other ones that we were operating, and the shortwave radios were all concentrated in that building. So for example, if you were posing on your radio as ND 98 or Moscara, you would have been tapping out your shortwave radio message. And the person at the other end would become very familiar with your technique for sending the message. It’s called fisting. So if there’s another agent, there has to be a different person fisting, because the person at the other end in Hamburg would become suspicious if there was the same person fisting for all of these. Is this making sense to you?

Devin (to Ray): Yeah, it does make sense.

Ray: I’ve spoken to men and women who were shortwave radio operators, amateur radio operators. And they can immediately tell a lot about the individual who is at the other end of the message simply by the fisting technique. It becomes almost like a fingerprint. So you can see why, if there are three or four double agents, you have to have three or four different people there, right? And they were living there, they were eating there – and this woman, she had to do all the cooking, she had all the cleaning. And at the same time, she is trying to raise and take care of a toddler. So it was a very difficult and arduous time for those people out there.

In one case, they had to use another cover story because one of the radio operators that they had out there decided that he wanted to join the military. So they had to come up with another cover story to explain why there was a new person fisting. And Seybold said, “I got another person because my current radio operator has been drafted into the military. So now I’ve had to find someone who was loyal to Germany, wants Germany to win, he’s from the German community, etc.” So they actually got another Bureau radio operator to replace that individual. So they ran into a lot of these headaches along the way, a lot of them just administrative and bureaucratic and dealing with personnel. You know, it’s typical of these longterm operations that life has a tendency to interfere.

Lauren: As part of keeping this site secret, one of the problems they had was the amount of electricity it took to broadcast these communications to Germany. It would be suspicious if this young couple was consuming so much electricity on a constant basis. So they had to figure out how they could produce their own electricity. And it turns out that they used a car engine in the basement as basically a generator to produce their own electricity. They placed the engine on a concrete block, and that’s one of the only pieces of physical evidence that remains in the house today that shows what this house was used for in the 1940s.

Devin: But let’s talk a little bit about the operation itself.

Lauren: First of all, the Germans were very interested to know where the Americans were at in the development of the atomic bomb. They felt the Americans were ahead in developing the bomb, when in reality, I don’t think that was really the case. But it was very clear that the atomic bomb – whoever learned how to harness that nature first, they were going to come out on top at the end of the war. So sending misinformation about how much progress the United States had made was one of the major components that was being sent to Germany.

Devin: You’re absolutely right. And that becomes known really early on when Moscara is first being interviewed by the FBI. He notes that the spy master in Germany, who was a guy named Hans Blum, mentioned that one of the things they were interested in, as you said, was where is the United States when it comes to what he called “smashing the atom.” At this point, nobody knew anything about that, even the FBI didn’t necessarily know what he was talking about. But in reality, the Germans were moving towards an atomic program. The FBI sent that information up the chain of command and all the way to the president, who eventually greenlit the atomic program in the United States based at least partially on this new espionage information.

Lauren: One of the other operations they had a major effect on was Operation Bodyguard, which was essentially feeding Germany false information about where the Allied invasion of Europe was going to take place. Of course, we know that it took place in Normandy, but at the time, the Wading River Radio Station was feeding information to Germany making it sound like the invasion was going to take place at Pas de Calais, which was the shortest distance, the shortest body of water in between England and France, where the Germans really thought that that was where the Allies were going to invade. And Operation Bodyguard really did a very convincing job, so the Germans did concentrate their forces in that area.

Devin: This was a massive operation. There were several radio stations taking part all over the world, feeding misinformation to the Germans. There was also an entire fake army of rubber tanks, an imaginary army that was supposed to be ready to pounce somewhere and in Europe, anywhere from Norway to Spain. So when the Germans were trying to figure out where they were going to land – because they knew an attack was imminent, they didn’t know where and they didn’t know when, but they knew that there was going to be an invasion – they assume that the Pas de Calais was was the most logical point, and everything else was a distraction, diverting their attention from the obvious.

So Wading River played a massive role in deceiving the Nazis, but it also deceived their allies, the Japanese. Because of the relationship between Germany and Japan at the time, the Germans were receiving information from Wading River Radio Station and then sending that to the Japanese, anything that had to do with the Pacific theater of war, including Operation Bluebird.

Lauren: They were trying to convince the Japanese that American forces were planning to invade Formosa off the south coast of China. And of course, we end up dropping the atomic bomb, and the Japanese surrender, so there was no invasion of Japan. But this is another way that counter-intelligence was helping to support these operations from the Wading River Radio Station.

Devin: And it’s pretty amazing to me how they did this. So they created not only these fictional double agents, but they also created their sources. There was a person that they named “Wash,” who they said was a high level War Department official, and someone named “Nevy,” who held a post at the Brooklyn Navy Yard – which we said earlier, was so important. Then there was “Rep,” who leaked vital aircraft production figures from the Republican Aircraft Company in Farmingdale. And “Officer,” who was supposed to have been a high level military officer traveling between New York and Washington. None of these people existed. They were all completely fabricated. But when the agents were transmitting information to the Nazis, they would say something like, “Wash said this,” or “Nevy said this,” and then they would tailor that information to whatever background these people were supposed to have. But it’s also interesting to realize that some of the information they were sending was actually true – that’s how you can really fool your enemy. You don’t just feed them absolute fabrication, you put in nuggets of truth. For example, Moscara was able to send information to the Nazis letting them know that a senior British officer would be replaced in the coming weeks. And he was, so that was true information. And so, the enemy, in this case, the Nazis, start to believe you more and more. And so other information that’s being fed to them, they are less likely to doubt.

Devin: So we know the operations at Wading River ended in 1945. We believe August of that year is when things finally wound down. But that was not the end of the story. Because shortly after the FBI left, there was actually a scene filmed on the back porch of the Owen house, and it was featured in the movie that came out later that year, called The House on 92nd Street – which was not about the Wading River Radio Station. It was a fictionalized account of the Seybold case. And the funny part about it is it was a film that was done in partnership with the FBI. So J. Edgar Hoover, the legendary head of the FBI, was in the film, as were several agents. So this film was kind of real, and it brings the question up of, did people really know what was going on there?

Matt: You can look at articles that were published in the 1940s. Some of this came out, not specifically what the work they were doing – that came only recently – but people in the area knew something was going on. We hear stories about neighbors hearing that there’s some covert operation going on at Owen place, and showing up in cars with shotguns because they thought they were Germans who landed in a U-boat or something like that. Because that was the fear, that there would be all these German U-boats in the Long Island Sound because Groton, Connecticut, which is the base, is right across the Sound from us. But basically, they said, “No, it’s an FBI operation. Go away.” And it’s a small town, so they all dispersed. But we do have a sense that people in the neighborhood work quietly said to go away.

Ray: I always wrack my brain as to how I came across it. It was serendipity a little bit. I had read The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes. And coincidental to that, I obtained through the Freedom of Information Act the file on ND 98, it was called the Rudolph case. They have all kinds of different code names. So I had the file, and I was going through the Moscara file, and all of a sudden I turn the page: whoa, here it says Wading River in New York. And here is the debriefing of Moscara, talking about the atomic bomb. I was stunned. I had never heard of that at all.

The first thing I did was I called the Wading River historian, and he said, “I’m familiar with the house, but I’ve never heard about this!” You know, the anniversary of the Normandy invasion was coming up. And I had a very enlightened president of the Society of former Special Agents of the FBI – they pulled out all the stops. And that’s what put it on the map. That’s how Newsday got involved, that’s how the media got involved. So I’m very proud of [it], and I’m very pleased that we were able to [put it on the map]. Now the William Pomeroy Foundation put up a plaque identifying it, it’s now on the National Register of Historic Places. So it’s great. It really really is another piece of information about Long Island history that we’re aware of.

Devin: It was essentially hidden for almost 70 years. It wasn’t until the 70th anniversary of D-Day in 2014 that a public announcement was made, and there was a local press event held by Dr. Batvinis and other FBI agents to announce the fact that Wading River Radio Station took place at the Owen house. And today, Camp DeWolfe, under the leadership of Reverend Matthew Tees, has really embraced their history and their connection to this period of time.

Lauren: I think there’s still new information that is being uncovered. It’s only been a few years that this information has started to come about, and as we know, as historians, the more you talk about a subject like this, the more people start to come out of the woodwork and say, “Well, I had a piece of this history,” or, “My family member talked about their involvement in this process.” This information, it has been declassified by the FBI, so there’s no chance that people will get in trouble having documents about this. So history is a changing story. It’s a book that we don’t know the ending to, and you never know when you’re going to find the next big story, because things get buried for a long time.

Devin: It’s absolutely true. You never really know what’s going on the house down the street.