On this month’s episode, Devin and Lauren explore the story of Plymouth Freeman, a black Patriot who served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and discuss how disenfranchised communities have harkened back to the promises outlined in the Declaration of Independence as a strategy for inclusion in those foundational principles of freedom and equality.

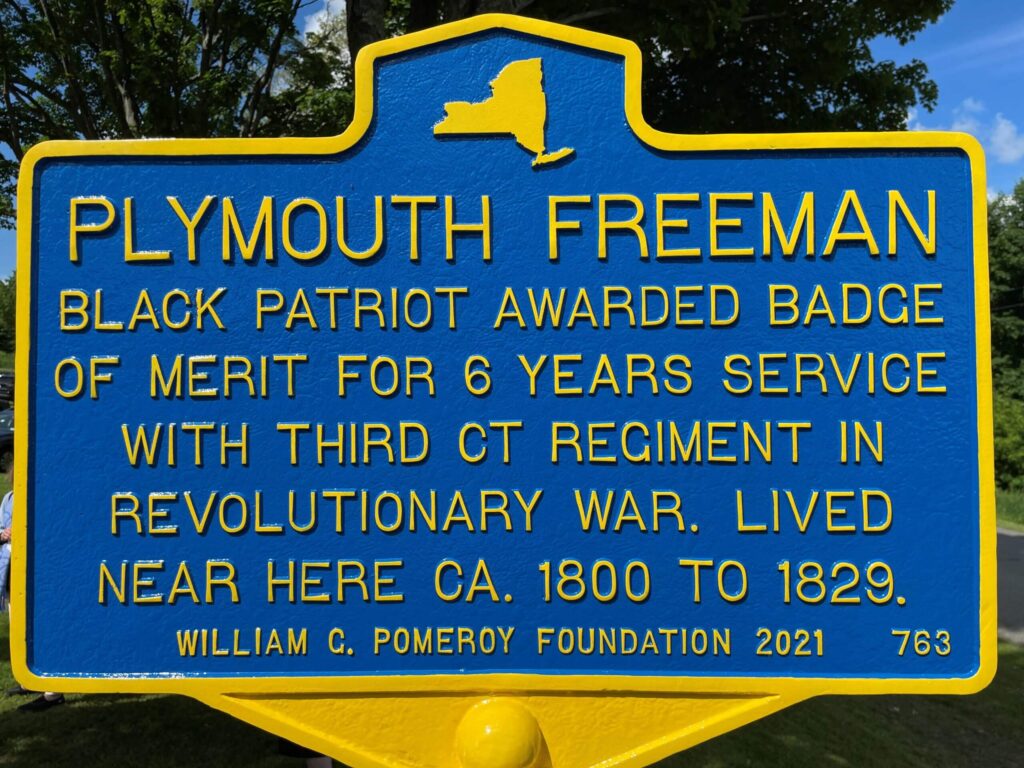

Marker of Focus: Plymouth Freeman, Madison County

Guests: Donna Wassall and Karen Christensen of the Fayetteville-Owahgena Chapter DAR, Paul and Mary Liz Stewart from the Underground Railroad Education Center, New York State Museum’s Chief Curator Dr. Jennifer Lemak and Senior Historian Ashley Hopkins-Benton.

A New York Minute in History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio and the New York State Museum, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Featured Image: Soldiers at the Siege of Yorktown (1781), by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine DeVerger

Further reading:

The New York State 250th Commemorative Field Guide—Office of State History and the Association of Public Historians of NYS.

Liberty Is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution by Woody Holton.

Slavery in New York edited by Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris.

Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad by Eric Foner.

My Bondage and My Freedom by Frederick Douglass.

Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State by Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello.

Votes for Women: Celebrating New York’s Suffrage Centennial Jennifer Lemak and Ashley Hopkins-Benton.

Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America by Charles Kaiser.

Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 by George Chauncey.

A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski.

Teaching Resources:

Consider the Source New York—New York State Archives Partnership Trust

The Underground Railroad Education Center

Votes for Women Online Exhibit—New York State Museum

Slavery in New York Educational Resources—New-York Historical Society

LGTBQ Teaching Resources—United Federation of Teachers

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York State historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On this episode, we’re focusing on a historic marker located on Putnam road in the town of Nelson, which is part of Madison County. The title of the marker is “Plymouth Freeman” and the text reads: Plymouth Freeman, black patriot awarded Badge of Merit for six years service with third Connecticut regiment in Revolutionary War. Lived near here circa 1800 to 1829. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2021.

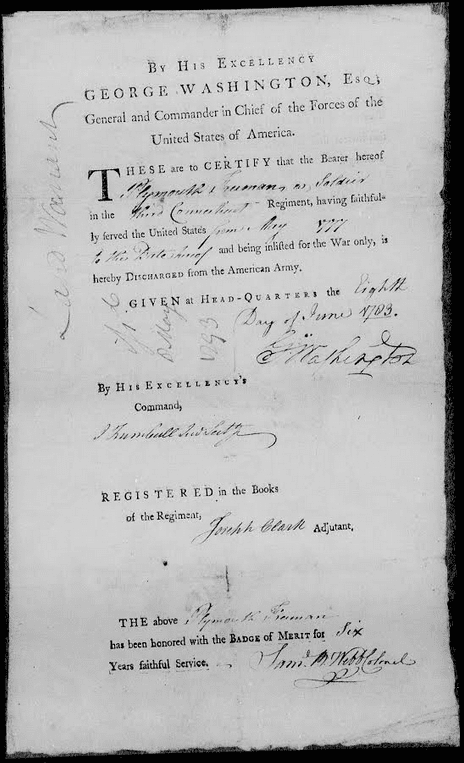

So we’re going to be talking about the story of Plymouth Freeman. Plymouth Freeman was a black man from Connecticut, who, as the sign says, served for six years in the American Revolution. He enlisted in Windsor, Connecticut in 1777, and served until he was discharged at the end of the war in 1783, at West Point. Although we don’t have a record that points to this, it appears as though he may have been an enslaved man, and that he may have been serving as a substitute for either the person who enslaved him or someone else. It’s not clear yet what the records are.

Devin: We spoke with Donna Wassall and Karen Christensen from the Fayetteville Owahgena Daughters of the American Revolution chapter to learn more about the research that they’ve done on Plymouth Freeman.

Donna Wassell: My name is Donna Wassell, and currently I’m the regent of the Fayetteville Owahgena chapter D.A.R. New York State Society. And I became interested in the organization after finding out that my great grandmother had been a member of the D.A.R. in Hartford, Connecticut, I myself have only been a member for six years.

Karen Christensen: My name is Karen Christiensen, and I’ve been for 31 years a member of the Fayetteville D.A.R. chapter. I became interested when my mother and I went to her cousin in Virginia, and found our nine times great grandfather’s headstone. And it says “sergeant in the Revolutionary War” on it. I was researching the history of the house Cazenovia for a friend – and saying, you know, who owned what, when, where and all that – as a housewarming gift. And I came across this article about Plymouth Freeman. And from there, it just kind of escalated. I thought it was very cool that there was a Cazenovia patriot of color, a free man of color, back way back during the Revolutionary War. So that’s what got me interested in it. I called Donna and of course, she’s the most curious person on earth. And, and, and we started to research it together.

Donna: Actually I have a very vivid recollection of this whole conversation. It was following one of our chapter meetings and she approached me and she said, “I read this article, and it’s about a freed slave who fought in the Revolution, and they settled in Cazenovia. And I think we should do the research to get a Pomeroy Marker for him,” is exactly how that went. So reading the article just opened up a whole world of unanswered questions, and that’s when we really started to dig in. Some of his history that was in the article was vague, and some of it was – sounded like it could have been lore or legend, and we weren’t quite sure. So I made a list of questions, and then we started from there.

The first place I went was Ancestry. We had seen copies of Plymouth’s discharge papers from the military. And I started searching “Plymouth Freeman” on Ancestry and all I could come up with were his discharge papers. I couldn’t find any information about him prior to 1782. I said, “Well, we know he served, he’s got to have muster records, they have to be out there somewhere.” I started searching “Plymouth” with no last name, “Plymouth, African American.” And finally I searched “Plymouth Negro,” and all kinds of wonderful records appeared. So he had enlisted under the name Plymouth Negro. And up until 1782, all of his military records were under the name of Plymouth negro. So that was, it was like hitting the motherload, I thought, when I started seeing all that information, Karen and I, Karen looked and we could never – she looked hard – and could not find manumission records for Plymouth. That’s one of the reasons on the Pomeroy marker, we could not put “former slave,” even though we believe he was, but we couldn’t put that because we didn’t have the documentation to prove that he had been manumitted.

It’s probably most of the common knowledge now that oftentimes enslaved persons would be substituted for their owners, sometimes with the promise of “you serve in my place, and you will, you’ll get your freedom.” And I knew that Plymouth enlistment date on his master records was dated May 26 1777. And I went through these books and found an enlistment record from May 26 1777. But it wasn’t Plymouth’s name. It was another local citizen’s name. And then, a few entries down in the same book was another entry that said that this man who had enlisted had paid £30 to substitute black man in his place. One of the questions that still needs to be answered is: Was this the guy that – did he, in fact, substitute Plymouth for himself? Or is there some other way this whole thing went about? But it’s interesting that the dates line up, and that they refer to an unnamed negro man who took his place. The legend or the lore that was going around and being published about Plymouth said that, you know, he was a former slave son of a king in Guinea, Africa, and that he had served in the Revolution as a cook to General Washington. And that intrigued me, and when I started finding his muster records dating back to 1777, when he enlisted, he was a servant to a general, but it wasn’t General Washington. He served almost the entire duration of his enlistment as a waiter to general Jedediah Huntington out of Norwich, Connecticut. That might seem like it’s a letdown because it’s not General Washington but once I started researching General Huntington, and his contributions and participation in the conflict, Plymouth’s life just it must have been fascinating and the things he would have seen and been exposed to as a waiter to General Huntington kind of still blows my mind when I think about it.

Lauren: Throughout those six years of service, he saw some pretty incredible historic moments, starting with Valley Forge, going through Monmouth, the mention of some really important trials, including Charles Lee and Major Andre. These are things that we learn about in basic American history. So to know that Plymouth freemen was part of all of these events, or was at least present at all of these events is really a remarkable past to have. And we know about these things through the research of pension papers, through muster rolls, were able to kind of follow Plymouth Freeman’s service through these major events.

Donna: These muster records are pretty thorough. I was able to get most all of them for the whole six years, and it’s pretty detailed about where they went. It would say, you know, “Plymouth Negro on command with general Huntington, Fairfield, Connecticut” or “at West Point,” you know, it would say exactly where they were. So some of the assignments that he was on with General Huntington was the Valley Forge encampment. In the spring of 1778, the both of them left for commission on the losses of Fort Montgomery and Clinton. In June 1778, they were at Monmouth during General Lee’s retreat. Also in the summer, General Huntington was assigned to the court martial of General Charles Lee. In the fall of 1780, General Huntington was assigned to be at the trial and hanging of Major John Andre, the accomplice to Benedict Arnold.

So I looked up also, besides finding out that according to the general’s orders, all men including the servants in the waiters be trained in military drill and able to bear arms. The other thing says is essentially they were like, I hate to use the words “man in waiting,” but they were like a personal valet, servant – they were at their beck and call, and everywhere that officer went, their man went with them. I think with that it’s safe to assume that Plymouth was with the general on all of those assignments that Huntington was on. And that said – going back to the legend about Plymouth being a cook to General Washington – General Huntington was a close confidant and comrade of General George Washington, they were friends before the war. So it is absolutely very possible that at some point Plymouth Freeman did either cook for or wait on General George Washington.

Lauren: You may be wondering if black men were integrated in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and in fact they were, and that’s something that wouldn’t happen again in the American army until the Korean War.

Devin: Yeah. And that’s an interesting point. And it brings up some interesting questions about someone like Plymouth Freeman, or any African American who served in the Revolutionary War. They were essentially serving on behalf of a country – that would become a country – that was a slave country. Now, some of these people were free blacks, they were already freed, and some, as we noted, with the possibility with Plymouth Freeman, that they would have been enslaved when they enlisted, and could have been a substitute for someone else. So it brings up some interesting questions about the ideals of the American Revolution and the language that was used by the people like Thomas Jefferson and the “founding fathers” of the nation, with regards to liberty, with regards to freedom. And it also raises some interesting questions about why someone would choose to serve the American side as opposed to the British side who were offering enslaved African Americans freedom if they came and served for them.

Lauren: Karen and Donna planned the dedication of the marker so that it was exactly 239 years to the day that Plymouth Freeman was discharged from service. And they were able to get a pretty great turnout for one of these events.

Donna: There was a book written in the 1800s by a reverend, W.W. Crane. [He] grew up in the town of Nelson, and he wrote a book about his childhood and he makes reference in his book to being friends with this boy, nicknamed Black Jerry, and Black Jerry was Jeremiah Freeman, who was Plymouth’s son. And in his book, he makes reference to [how] Black Jerry would always tell him how his dad, you know, had been a slave and served in the Revolution and waited on George Washington, and all these things. So between where I know that the Reverend Crane lived as a child, and what the Town of Nelson historian was able to put together, we were able to pinpoint within a short distance where Plymouth would have lived. So he was right in the Cazenovia/Nelson area until probably, you know, not long before his death. We do not know where he’s buried. That’s Karen’s burning desire, but trying to figure out where his remains lie. I don’t know. Other people have looked; they’ve been looking for 200 years to find where he is.

The day of the marker dedication: It’s on a little secondary side road right off Route 20 in the town of Nelson, on some guy’s front lawn, because he was gracious enough to let us put it there. We put a lot of press out before the marker dedication, and I would say we had probably 70 people at this thing. We had history teachers from the local school, we had some local dignitaries, the President General of the Daughters of the American Revolution showed up. It was amazing. And there were some people that had heard the story, and there were others who had never heard of it. And then there were others that were so grateful that a person of color was honored in this way for fighting in the Revolution. And we had a follow up article that went out after in the woman for the local news who did the article, I think it was a two-page spread. It wasn’t just like, “Daughters of the American Revolution host a marker [dedication],” it was his entire history. Right off the biography that we had read at the ceremony.

I think, yes, of course, Karen, I’m sure, and I – I know every chance I get to talk about it, I talk about it. Because it’s a fascinating story. It really is. And I mean, Plymouth’s this one guy, one former slave, African American man who went and fought for freedoms that potentially wasn’t gonna have, and did it honorably and was recognized for that.

Lauren: I think it’s interesting that they just happened to come across this article in 2019, that mentions him, and, and then you fall down the rabbit hole of trying to research this person. And especially, you know, when it is a minority, or a black person from the 18th century, trying to find those records is really difficult. We have to commend those women for the research they were able to do and you know, you just wait for those needle-in-a-haystack moments to try and uncover these little bits of information to piece together the story.

Devin: I think this story of Plymouth Freeman is a fascinating story as we’ve gone through it. It’s an incomplete story because of the records. And maybe these records will be found, as Donna and Karen continue their Odyssey to discover more about Plymouth, but it really brings to light some of the dichotomies that existed in the American Revolution. We think about the American Revolution as this revolutionary event. And it really was, it was a world-changing event. But in other ways, it was very much of its time, as I said, the United States, as it became known, was a slave nation. Also, half of the population was not given the right to vote, or the right to do much of anything, including owning property, and that’s women. But over time, because of the ability to change the constitution and amend it. It really led to a series of other revolutions.

On October 22 2023, I moderated a panel of experts on the concept of the unfinished revolution in New York State.

Devin (at presentation): My name is Devin Lander. I’m the New York State historian here at the State Museum. And I just want to welcome all of you. As we’ve been thinking about how to commemorate the American Revolution. It’s very clear as historians that the revolution itself was incomplete. This is something that’s echoed in the founding legislation that creates a state commission in the state of New York:

“The legislature finds that New York played an immense role in the lead up and execution of the American Revolution during the period of 1774 to 1783, and was the site of several important battles, skirmishes and other events that were internationally significant during the Revolutionary era. The American Revolution itself was imperfect, and many – including women, African Americans and Native Americans – did not benefit from its ideals of liberty and freedom. However, the struggle to fully realize the ideals of the revolution has continued over the past 250 years, as is evident in New York’s leading role in such revolutionary civil rights movements, as the women’s rights and abolitionist movements, the Underground Railroad and the LGBTQ movement. The commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution should also be an occasion for recognition of New York’s vital role in the revolution itself as well as the ongoing struggle of marginalized peoples to achieve the ideals of the revolution.”

So this panel has been assembled to talk about New York’s role in these kinds of continuing revolutions. To my right is Paul Stewart. He is the co-founder with Mary Liz of the Underground Railroad Education Center. Next to Paul, is Mary Liz Stewart. She has an active background supporting nonprofit organizations, cultural heritage organizations, and museums. Next to Mary Liz is Ashley Hopkins Benton. She is a senior historian and curator of social history for the State Museum. Final on our panel is Dr. Jennifer Lemack, who is the chief curator of the New York State Museum. So thank you all for joining us, and we will begin our discussion.

But let’s start with, kind of the beginning with America’s founding documents: How have America’s founding documents been used to press for social, political and economic change beyond the founding of the United States itself?

Paul Stewart: That’s a great place to jump in. Because particularly when we think about the Declaration of Independence, you know, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” that, although it was used as a theme at that moment, to the American Revolution, and I think their intent was to contrast that with the British nobility, and to sort of say that the king wasn’t any better than they were. But I think implied in what they said there, was that there were rights that were inherent that were extended, and you began to see that almost right away reflected in the concern of African Americans for asserting rights within the context of the United States. It was a very strong theme within the movement that we’d come to call the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement, it continued to echo throughout. And of course, today, in this day and age, it is still something that we can use as a touchstone to talk about moving forward to create a more perfect society, and to bring those rights, or recognize those rights, assert those rights, in the context that we see them today that where they need to be asserted and defended.

Mary Liz Stewart: I’ll take it a step further, with a reference to our black abolitionists, based in the research that Paul and I have been doing over the years. And we came to recognize that for our block abolitionists, while their primary concern – as with white abolitionists – was for the elimination or abolition of the institution of enslavement in the state, in the nation – we noticed that our lock abolitionists took some extra steps which was to engage in a variety of state-based and nationally-based activities. For instance, there was the existence of an organization called the American Council of Colored Laborers that had a home here in New York State. We have the New York State Suffrage Association. We have education also being a focus of attention for many of these black men. In fact, in particular, here in the city of Albany, the city school district of Albany was sued because it refused to let black children through its doors, and the legal case was initially resolved in 1851, which only to find out that the application of the legislation applied only to the children of Stephen and Harriet Meyers. So city residents took up the cause and continued the pursuit of equity in education here in the city of Albany. The relationship between these kinds of civil rights activities, really in relationship to those promises, laid out in the preamble become very explicitly engaged in by our black abolitionists.

Ashley Hopkins-Benton: As I look across the history – especially of the women’s rights movement, and the LGBTQ+ rights movement – what I see is trying to find the ways in which those groups fit into those documents and can place themselves in the history that maybe they were omitted from in the beginning.

So in 1848, and Seneca Falls, The Declaration of Sentiments is delivered, describing the demands of women and it starts “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal.” So they are co-opting that document. And then by the 1970s. The Women’s Declaration of Independence is rewritten again by Serena Hanson and Sidney Pendleton. And again, taking that initial document and reworking it to talk about the ways that women are still left out of society in the 1970s.

In the 1870s. Francis Minor declares that women aren’t left out of the Constitution and voting rights and that they should go try to start voting. And so in 1872, Susan B. Anthony and fifteen women from Rochester test that out, and are arrested because some say that they are wrong in that assertion. Also, in arguments for LGBTQ+ rights, they pull little bits and pieces and ways that they see that they fit. So then in 2015 in Obergefell v. Hodges, which is the Supreme Court case that eventually allows marriage equality, Justice Kennedy in the ruling says that “the plaintiffs ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The constitution grants them that right.” And he is looking back to the 14th Amendment finding these bits that aren’t explicitly about the LGBTQ community, but can provide them protections.

Dr Jennifer Lemack: One of my favorite examples of, kind of harkening back to our founding documents and principles, is the New York State Suffrage campaign of 1894. They calculated how much women pay in property taxes. And what comes next is the cry that “taxation without representation is tyranny.” So harkening back to the founding fathers and our original patriots, and they mounted a huge campaign, and they sent out 5000 petitions across the state, and they were able to get over a half a million signatures, and they presented the signatures very dramatically to the New York State Legislature, and they were voted down.

One of our prized artifacts here at the State Museum, is the Spirit of ‘76 Suffrage Wagon, which in 1913, in Long Island, Edna Kearns and Irene Davidson dressed as Minutemen, and carrying signs that said, “Taxation without representation is tyranny,” rode the wagon from Long Island to New York City for a parade in September 1913, one of their daughters was dressed as Lady Liberty. So the suffragists constantly used this revolutionary rhetoric to get their points across.

Lauren: Recently, I attended the 2023 reenactment of the Boston Tea Party. And as part of that commemoration, the reenactors made a point to include that not everyone was included in the meeting of the body of the people where it was decided that the tea would be dumped in the harbor, they actually use the narrator Phyllis Wheatley, who was a woman of color, a poet, [a] formerly enslaved person whose book of poetry was actually being delivered on the same ship as one of the ships that was holding tea. And the point is made that people like her were not invited to participate, yet they still had to suffer along with the consequences of those decisions made by those that had the right to have a say. So when we think about the commemorations of the 250th, looking at a broader context of who was and was not represented, but also the means that were used to get their point across to King George about wanting fair representation, and wanting to be able to govern themselves for some in the colony.

Devin: It also gives us an opportunity to think about the American Revolution as an ongoing revolution, and we’re still living in the ripples. And in our case in the United States and the New York. It’s been a series of other struggles, and other revolutions, and we’re still living that history.

Lauren: Thanks for listening to A New York Minute in History. This podcast is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio and the New York State Museum, with support from the William G. Pomeroy foundation. Our producer is Elizabeth Urbanczyk.

Devin: A big thanks to Donna Wassell, Karen Christensen, Paul and Mary Liz Stewart, Dr. Jennifer Lemack, and Ashley Hopkins-Benton for taking part in this month’s episode.

Lauren: To learn more about our guests and the show, check us out at WAMCpodcasts.org. We’re also on X and Instagram as @NYHistoryMinute.

Devin: I’m Devin Lander,

Lauren: …and I’m Lauren Roberts.

Devin: Until next time:

Both: Excelsior!