On this episode, Devin and Lauren delve into the history of the Dutch patroon system in New York state, and tell the story of the anti-rent movement of the 19th Century, during which tenant farmers banded together to (sometimes, violently) oppose the outdated system. In the Albany County town of Berne, tenant delegates from 11 counties gathered for a formal Anti-Rent Convention in 1845.

Marker of Focus: Anti-Rent Convention, Berne, Albany County

Guests: Dr. Charles McCurdy, author of Anti-Rent Era in New York Law and Politics, 1839-1865; and Sandra Kisselback, town of Berne historian

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with help from intern Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

This episode contains music created by Sean Riley. It also features the following pieces from the 2015 Old Songs production “Down with the Rent,” including “The Farmer is the Man” (written by Knowles Shaw, 1834-1878; sung by Terry Leonino and Greg Artzner and company) and “We Will Be Free” (text by S.H. Foster; tune “The Boatman’s Dance” sung by Terry Leonino and Greg Artzner and company).

Further Reading:

Charles McCurdy, Anti-Rent Era in New York Law and Politics, 1839-1865

Dorothy Kubik, A Free Soil- A Free People: The Anti-Rent War in Delaware County, New York

Albert Champlin Mayham, The Anti-Rent War on Blenheim Hill: An Episode of the 40’s

Teaching Resources:

Consider the Source New York, Anti-Rent Senate Documents

New York State Archives, Primary Source Inquiries, Anti-Rent Wars

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On today’s episode, we’re focusing on a historic marker located at 1728 Helderberg Trail in the town of Berne, which is located in Albany County. The marker stands in front of the Helderberg Evangelical Lutheran Church, and the text reads: “Anti-rent convention held here, January 15, 1845. Delegates from 11 counties petitioned state to end unjust land lease system. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2016.”

The church that the sign sits in front of is now called the Helderberg Evangelical Lutheran Church, but back in the late 1700s, it was referred to as St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, and it played a really important role in the anti-rent movement. Before we start speaking specifically about why this anti-rent convention was important, let’s give a little refresher about landownership in parts of New York’s Hudson Valley, and explain why there was an anti-rent movement in the first place.

First, we have to remember that in the early 1600s, it was the Dutch government that controlled the area that we now call the Hudson Valley. Beginning in 1629, the Dutch issued the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions, which allowed for investors in the Dutch West India Company to be granted large swaths of land – we’re talking hundreds of thousands of acres. And they were referred to as patroons.

Charles: Once upon a time, the land was all owned by a handful of big shots. And the big shots would convey a piece of the land to tenants.

Devin: I spoke with Dr. Charles W. McCurdy, author of The Anti-Rent Era in New York Law and Politics, 1839-1865.

Charles: Tenants, they would hold “of the landlord.” In other words, they didn’t own what we would today called a fee simple title, the way we own our suburban homes, for example, and farms. They would hold of the landlords, so the true owner would be the landlord, not the tenant. This went on in perpetuity. So, if you were the son of a tenant, you would inherit the same land on the same terms as your father had. And this would go on for generations, potentially.

Lauren: They could sell the land. They could also pass it down to their heirs, so that the land would always remain within the family. However, they never owned it. They always had to pay a yearly rent, and that rent was usually paid in crops or in fowl, livestock. And the patroons had an overwhelming amount of power. It wasn’t just that they were huge landowners, but they also had the ability to create their own court system, which meant that they didn’t have to follow the same justice system as the rest of the government. They really had a feudal land system where they were the complete power over any of their tenants.

Devin: So the patroon system starts as a Dutch creation. But in 1664, we know that England takes over the colony, and they continue this system as a manor system. They’re still sometimes called patroonships, even after the British take over. The largest and most successful patroonship was established by diamond and pearl merchant Kiliaen Van Rensselaer in 1630, and he called it Rensselaerswyck.

Charles: The manner of Rensselaerswyck occupied, except the northern townships in Rensselaer County, the whole county – all the way to the Massachusetts line from the Hudson River. And the same estate extended through all of Albany County except a little chunk called Coeymans. That’s 48 miles from the western boundary of Albany County, to the Massachusetts line. That’s 48 miles, and it was 48 miles up and down the Hudson River. Well over a million acres.

Devin: Rensselaerswyck was passed down from generation to generation in the Van Rensselaer family – always the men of course, the dominant heirs – until the early 19th Century, when Steven Van Rensselaer III inherited the patroonship. And he had a different way of dealing with the tenant system.

Charles: Van Rensselaer was a man known for great benevolence. He founded what’s now RPI, built all the Dutch Reformed churches in the whole valley. He was on the Board of Regents for the state university. He was the chair of the Erie Canal board. I mean, his benevolence and stature as a good guy was legendary.

He said, “You can’t get land on better terms anywhere in the United States as you can in Albany and Rensselaer counties, my land. Because if you enter the land, I’ll give you a lease that will last forever, you will acquire an inheritable piece of land. You won’t pay any rent at all for the first seven years. And in return for that, I’m going to want my annual rents payable in wheat after seven years in perpetuity. Plus, if you sell the land, you owe me one quarter of the purchase price.” Well, in Rensselaer and Albany Counties, the population grew fivefold from the 1780s to 1820. So a lot of families took up this land.

Now this could have gone on for a long time. But in 1819, there was a financial panic, and there was an ensuing depression. Meanwhile, there’s new settlements in the west, in Ohio country, and the Erie Canal was completed. And farmers are starting to have lower yields, because of the hessian fly and other problems that farmers everywhere had. But their yields were going down, and meanwhile, their rents were going up. Because the price of grain soared beginning in 1824. And by 1836, the price of grain was 10 times what it was in 1786. So basically, the terms had changed, hadn’t they? What looked like a good deal in 1786 now, suddenly, looks like a very bad deal – at the very time when your own yields of grain are going down. You can’t go borrow money to save your farm to pay the rents. No mortgage company is going to loan you money if the first person on a foreclosure sale is going to be the landlord, who’s going to get at least one quarter, right? All right, so a rock and a hard place. And then in 1839, Steven Van Rensselaer III dies.

Rents hadn’t been collected since 1819. The tenants all thought, “Well, he’s just gonna waive the rents, maybe even convey the land to us in his will.” No, he had debts himself. And the first job of his two sons was to collect and pay off those debts.

Lauren: Steven Van Rensselaer III hadn’t collected rent in 20 years – and he was a wealthy man, but he was also a spending man. So the debts were high, and really, Steven Van Rensselaer IV needed to collect all of the rents, including back rents for the last 20 years, in order to pay off his father’s debts. So now we’re in a situation where there are thousands and thousands of tenants who haven’t paid rent in 20 years, wheat prices are not the same as they were, and the lands are not as productive as they had been in the past. And as you can imagine, the tenants were not thrilled about this change in policy.

Charles: They held a meeting. And on the Fourth of July, they declared their independence from the so-called “Patroon of the manor of Rensselaerswyck.”

Devin: So what does a patroon do at this point? Well, they involve law enforcement.

Charles: The indentures through which the families entered the land in the first place provided that if rent was unpaid for 30 days, all the landlord had to do was to show up with the sheriff and grab anything he saw, and sell it to pay the rent. That’s a good way to make sure that the rents are paid, if the landlord can just show up and take tools or growing crops or chattels, and sell them to anybody. And then the second way is just to eject, just to evict – put all the farm implements and stuff in the road, toss them off the land, and then you can lease it forever to somebody else.

Devin: They start sending the sheriffs and law enforcement of the era into these communities to break up these organizations and organized meetings that are taking place among the tenants, and that does not go over well with the tenant farmers.

Lauren: And we have to remember that the side of the law is on the side of the patroonship, because these tenants have signed leases which state that they will pay a yearly rent forever in perpetuity.

Devin: So the attempts to coerce don’t go over too well, as I noted. Many of the law enforcement officials and sheriffs are actually run out of these small towns and communities after being tarred and feathered.

Charles: They threatened county officials, all of whom are elected, that if they show up trying to distrain (that’s the process of just grabbing any chattel and selling it) or eject a family, they’re gonna go home in a wagon. We’re going to tar and feather the customs informers. We’re going to tar and feather sheriffs who tried to collect money from us on behalf of the pretended patroon of Rensselaerswyck.

Now, we’ve got politics deeply involved. If the county officials won’t do their job – and they didn’t want to after several attempts. The third attempt, they raised a local militia company in the city of Albany and marched out toward a little town called Reedsville. It’s about 20 miles to the west up in the Helderberg hills, and they met a screaming mob of thousands. So, if the sheriffs can’t enforce the law, they asked the governor.

There are about as many Democrats as Whigs in Albany County in 1839. The governor and his friend Thurlow Weed are very good at counting votes. So, it begins. Governor William Seward, later famous as secretary of state under Lincoln. He promises land reform, because the leases enforced on the manor of Rensselaerwyck are “anti-republican and oppressive.” That’s strong language in 1830: “anti-republican and oppressive.” And he calls for their abolition.

Devin: So, the anti-rent movement becomes kind of a political hot potato, as both the major political parties at the time – the Democrats and the Whigs in New York – tried to co-opt the movement and use it for their own political gains. And because it’s so large and encompasses so many voters, it really does have a political effect. Both the Democrats and the Whigs kind of take turns siding with the anti-rent tenant farmers and saying that they’re going to affect change through the legislative process or through other legal processes, but they’re never really able to do that.

Lauren: So Devin, we’re talking in particular about the manor of Rensselaerswyck, but there were others, say, Livingston Manor. What happened? Why is it that these manors live on in the Hudson Valley, and we don’t hear so much about the other lower counties?

Devin: I think that’s really interesting, because we’re talking about a feudal system that even in Great Britain hadn’t been used since like the 12th Century – but it was still in use even after the American Revolution, right? We’re talking about the early 19th Century, when Steven Van Rensselaer III dies in 1839. That’s decades after the American Revolution, where we’re supposed to have freedom and equality and all of these things. So why does the patroon system continue on after the American Revolution? It’s really because those who sided on the side of the American cause, or the Patriot cause during the Revolution, were allowed to keep their patroonship intact. Those who are loyalists and stayed loyal to the king? They lost everything. So that’s really how it continues on.

Lauren: In the early 1840s, one of the tactics that the tenants used was to disguise themselves as Indians – they called themselves the Calico Indians, which is a made-up name – but they would disguise themselves in robes and sheepshead masks to hide their identity. And the lore is that tenants who needed help when the sheriff or deputies were coming to their farms, they would blow on a tin horn, that sound would alert the Calico Indians to then come to their defense, and they would drive off the authorities.

Charles: The whole function is to make sure that nobody gets thrown off the land. That’s in Anti-Renters Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1839. Everybody pledges each unto the other that they will prevent the ejectment of themselves or their neighbors. People live that and it becomes the most important thing in their lives for a long time.

Now, the rents still aren’t collected. The politicians haven’t been able to figure how to abolish this extraordinary form of land tenure. And the landlords are getting impatient. So, they advance in 1844, on a couple of fronts in Albany and Rensselaer Counties, and it becomes clear to the leaders of the anti-rent movement that the best thing for them to do is to expand the number of families who are involved. So, they organize an anti-rent movement in Greene County, and they create a band of Indians to tar and feather the sheriff in Greene. And then the guys who were trained in Greene marched over into Delaware County, where there are thousands of people – not to the Van Rensselaers, these are mostly Livingston leases. And then finally the most famous anti-renter of them all, “Big Thunder” – Smith Bouton, who was a country doctor in Rensselaer County – he leads a band of Braves into Columbia County. Now, the anti-rent movement isn’t just two counties. It’s a big regional movement. It has substantial political power. And then there’s violence.

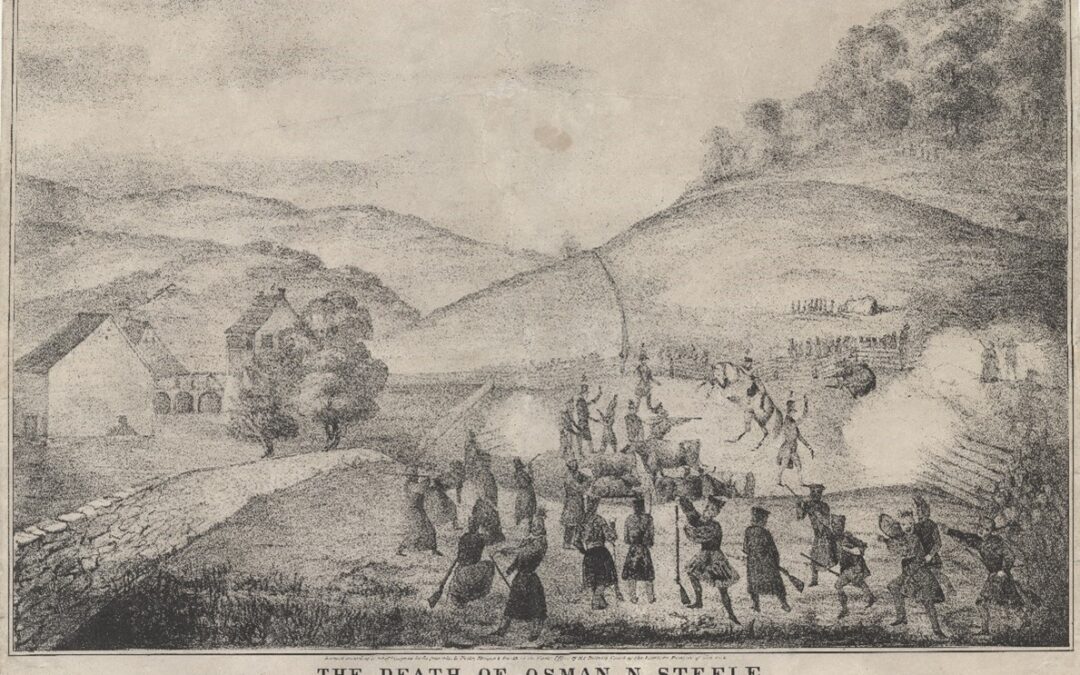

Lauren: Before it gets better, it starts to get worse. There are more episodes of violence, and people are killed. A young boy is killed by a stray shot at one of these clashes. And then a deputy sheriff is also killed trying to collect rent.

Devin: In very early January of 1845, the governor at the time, Governor Bouck, actually called up a militia to disband the Calico Indians, and about 300 militiamen arrived in the town of Hudson from New York City and Albany to crush the Indian rebellion. And several dozen of the Calico Indians were actually arrested and charged with inciting a riot.

Lauren: And so this prompts the legal system and the political system to try to find a way to ease these tensions, because the movement is growing and growing. In fact, in 1845, which is when the anti-rent convention happens that is referred to in the historic marker, there are representatives from 11 different counties that are joining this movement. They pack in 150 delegates to the church in the town of Berne to talk about how they can use their numbers in a political way to effect change.

To learn more about the local legacy of the anti-renters and the convention of 1845, we spoke with Town of Berne Historian Sandra Kisselback.

Sandra: From what I understand, there was people who came to the town from 11 different counties. Of course, the place was overflowing.

Lauren: Do you know what the reaction of the community was? Were the majority of people in Berne members of the anti-rent party, or was there opposition there? Do you know what the feelings of the surrounding community were?

Sandra: Yes, I think they were definitely supportive of it.

We have a museum. It’s on the second floor of an old hotel that people rented out when they were passing through town. There’s about eight rooms of history, and they have one huge sign that I know of. That’s the poster that was calling people to rise to the revolution. “Take up the ball of the revolution,” I think it says – that’s the first thing you see when you walk up the stairs. And then one thing they did, which was phenomenal, in 1975 they had the man who wrote Tin Horns and Calico, which is quite an in-depth telling of the anti-rent wars, they asked him if they could reprint that book. And he gave them permission. So they did that for the bicentennial. And that really brought more attention to the anti-rent wars.

Lauren: So the history of the anti-rent wars are pretty well known in your community?

Sandra: With the older people, I think. And then there’s one teacher who makes the kids aware. The school allowed the children to walk to the museum, which wasn’t that far away. We still have a lot of interest in the town, and I think we’ll get it back going again.

Charles: In the New York State Legislature in 1860, the last remnant of the anti-rent movement still has a legislative agenda. And that agenda is worked into a statute, the Anti-Rent Act of 1860, which the New York Supreme Court declares unconstitutional in 1863. But that ruling came down just as all the troops in New York were either putting down the draft riot in Manhattan or out on the front in Virginia. So there’s not an armed body of men that can go and clean out the last of the anti-renters in Albany County until the grand review of troops in the aftermath of Appomattox in 1865. Almost immediately after Appomattox, they marched into Albany County. They go to a guy named Ball’s house – he had taken a case all the way to New York Court of Appeals, and Ball had had already been ejected in 1860. They put all his furniture and stuff out in the road, and when the retinue went back to Albany, they just moved everything back in. [But now the troops are back to move them out for good]

The Albany County artillery actually marches out with a cannon and lots of weapons. There’s a lot of Civil War talk, because this is like “Putting down the rebels, buddy.” “Let’s proceed with the work of confiscation,” says the Albany Evening Journal. “We’ve confiscated their slaves and let’s confiscate these rebels’ lands which they have unfairly held without paying rent, in defiance of New York law,” sometimes since 1820. There was no longer a way forward to abolish or even mitigate the effects of the lease and fee, and so the only solution was state violence – just as the only solution to the secession crisis was state violence. There are massive ejectments. A lot of families however, bargained with the then owner – no longer Van Rensselaer, but an investor. They pay the back rents, pay interest on the back rents, and they keep their land, but they’re still holding in perpetuity, according to New York law.

Devin: So what happened with this whole movement? Did they actually accomplish anything? Well, we know the patroon system doesn’t exist anymore. But it wasn’t really a legislative or even congressional or constitutional amendment that ended things. And I would like to quote from Charles W. McCurdy, his book, in what he suggests happened at the end. He writes, “At the end of the era, the lease and fee no longer presented a problem to be solved. It served instead as a symbol of the self-defeating posturing by landlords and tenants alike. Both spurned compromise, both posed as noble victims deprived of their rights, and both blamed their unhappy fate on the corrosive interaction between law and politics. In 1865, nobody else cared.”

He’s really suggesting that after the Civil War, the issue just kind of disappears because people don’t care about it, and there are other bigger problems to consider in the nation. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a legacy. We’re talking about it today, books are being written, articles are being written, historic markers are being put up. So, we know that it does have a resonance in this part of North America, this part of the United States. And we do know that it’s historically significant, because it was a major movement – it’s still considered to be the largest tenant movement in the nation’s history. I think for that alone, it really is something we should be talking about and learning about. It’s a very complex situation. There’s very complex legal definitions that are being used. But it’s important for us to acknowledge that this was a system that was archaic, even during that time, it was archaic. And it was something that, you know, those who were tenant farmers really felt strongly about, that they were being taken advantage of. And so did the landlords who thought, “Wait a second, you haven’t paid rent in 20 years! And you signed this contract, and you’re supposed to pay us this rent, and all we’re doing is asking you to fulfill your contract.” So again, they’re being portraying themselves as victims, the tenant farmers are portraying themselves as victims, and an uprise against these, you know, landed gentry and the wealthy elite. And meanwhile, neither side is willing to compromise. And then you have the political side of things, where both political parties are trying to use the issue for their own political means. So they’re not necessarily interested in compromise, either. And as a result, unfortunately, you have violence, you have people actually losing their lives – not in great numbers, but any number is unfortunate. And I think for those reasons, it’s an interesting aspect of a very uniquely New York story.

Lauren: And it’s a story that doesn’t end with this, right? We still have tensions between landlords and tenants, not in the manor system, but certainly in situations where people are renting housing. We see this continue. We have a complicated relationship, not only with land, but with housing. And that continues right into the 21st Century. We still have protests going on, and we still have a situation where landlords and tenants are not willing to compromise with each other – and so the fight goes on.

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with help from intern Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.