In honor of Women’s History Month, Devin and Lauren highlight a Pomeroy marker in Tioga County and tell the story of Corporal Margaret Hastings, a member of the Women’s Army Corps who survived 47 days in a New Guinea jungle during World War II.

Marker of Focus: World War II, Owego, Tioga County

Guests: Mitchell Zuckoff, author of Lost in Shangri-La; Emma Sedore, Tioga County historian

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Lost in Shangri-La by Mitchell Zuckoff

Women For Victory Vol 2: The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) (American Servicewomen in World War II: History & Uniform Series, 2) by Katy Endruschat Goebel

The Ghost Mountain Boys: Their Epic March and the Terrifying Battle for New Guinea–The Forgotten War of the South Pacific by James Campbell

Teaching Resources:

Women in the Army: The Creation of the Women’s Auxiliary Corps

PBS Learning Media: Corporal Margaret Hastings

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

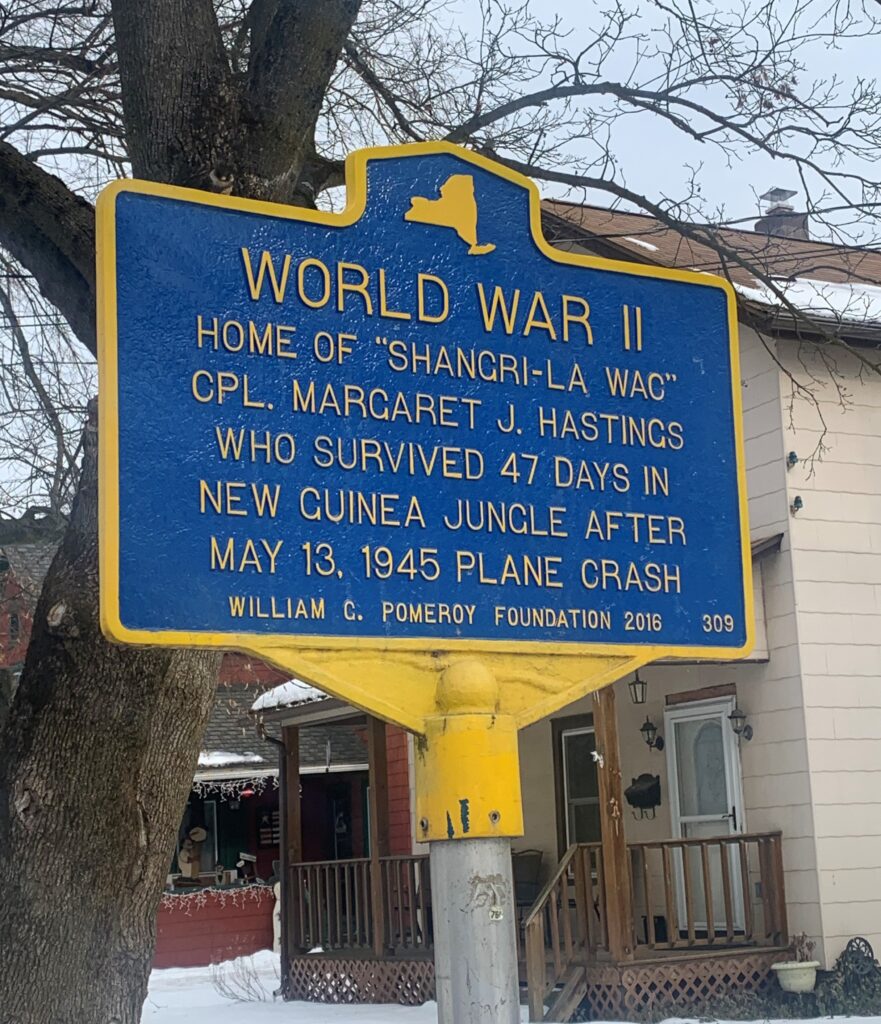

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. In honor of Women’s History Month, we have a fascinating account for you that includes tragedy, survival, ingenuity and an amazing plan of rescue. We begin the story in the village of Owego, which is located in Tioga County, in the Southern Tier region of New York. The William G. Pomeroy historic marker is located in front of 106 McMaster Street, and the text reads: “World War II. Home of Shangri-La WAC, Corporal Margaret J. Hastings, who survived 47 days in New Guinea jungle after May 13, 1945 plane crash. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2016.”

So there’s quite a lot to unpack from those few lines of text. But let’s start at the beginning. The sign is marking the former home of Corporal Margaret Hastings, so who was she? We spoke with Tioga County Historian Emma Sedore, who told us a little bit more about what Margaret’s life was like growing up in Owego.

Emma: One day at the museum, this man comes in with a big scrapbook. He said he’s a builder, and he was taking a barn down in Ithaca when he found the scrapbook – and it happened to be Margaret Hastings’ personal scrapbook. It had photographs and letters, and it had the telegram that went to her father when she went missing – oh my God, it was amazing. So I said to the director, “I’ll take it! I’ll index it!” And one day when I went into the museum, the director said to me, “This gentleman is gonna write a book about her.” I looked up, and there’s this handsome guy at the copy machine. I said, “Oh!” and he introduced himself.

Mitchell: I’m Mitchell Zuckoff. I’m a former newspaper reporter for The Boston Globe, and I write narrative nonfiction. I came across a Chicago Tribune headline: “Glider Rescue in Shangri-La Delayed by Clouds.” It sounded to me like an April Fool’s kind of headline – it’s just too crazy. It was a Chicago Tribune story by Walter Simmons, and he just started describing that there was this plane crash in the highlands of New Guinea, in this lost valley. And there were three American survivors, and one of them was a member of the Women’s Army Corps…One thing after another just made me stop everything and say, “How do I not know this?” For someone who focuses on World War II, how has no one ever written a book about this?

Emma: And I gave him all the information [I had]. I had a folder that probably weighed two pounds of all kinds of collections I had about Margaret Hastings.

She grew up in Owego. She graduated from Owego Free Academy, and then she was a private secretary for 10 long years. She never wanted to get married, she was very independent. She had two younger sisters – her mother died when she was a teenager, and so Margaret often was like a mother to her two sisters. I think she probably thought to herself, “Well, this is the same old, same old. How long am I gonna do it?” And probably when she turned 30, maybe like the rest of us, she said “I’ve got to do something different.” And that’s when she joined the WACs in January 1944.

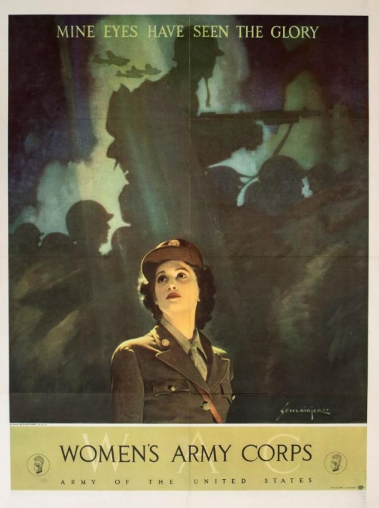

Devin: So what were the WACs? Well, they initially started as the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in 1942, and they were really a branch of the U.S. Army that was dedicated to doing secretarial work and other kinds of logistics work at army bases throughout Europe and the Pacific. In 1943, they became an active duty unit of the army and changed their name to the Women’s Army Corps. So the WACs, as they were famously known — somebody like Margaret, who was trained as a secretary, of course, her skill set would lead to be a secretary at the military base. And that’s exactly what happened. She was stationed in a place called Hollandia, in New Guinea. This is 1945, this is actually after the European theater is essentially over, but the Pacific theater was still very active. New Guinea had been essentially cleared of Japanese forces, but there were still an estimated 10,000 of them living in the jungle, cut off from the rest of the Japanese army. So New Guinea was a very dangerous place.

Mitchell: Hollandia is now called Jayapura, and it’s on the north coast of New Guinea. It was then and even to this day: it’s a largely uncharted, deep rainforest, with enormous numbers of individual native tribes, many of whom, up till the 1940s, had never been contacted by anyone in what we would call the modern world. And life in Hollandia was really, really hard. I think it was spectacularly beautiful, but the conditions were really brutal. The Women’s Army Corps members said the biggest variety was that there were five different kinds of jungle rot you could suffer from. They worked tremendously hard. They worked six-and-a-half or more days a week from the war effort. [There were] spiders the size of dinner plates, they said, and that was the easy part.

Devin: One of the ways the officers came up with to produce some sort of relaxation and entertainment was to travel to the recently rediscovered valley of Shangri-La.

Lauren: The word “Shangri-La,” it’s probably something that we’ve heard, but maybe we don’t know where it comes from. It actually comes from the book Lost Horizon, which was a novel written in 1933 by author James Hilton. Shangri-La actually refers to a fictional place talked about in this novel, and it’s supposed to be kind of an idyllic place on earth. It’s hidden away, it’s untouched by time. So you can see the connection between the area where they were flying over, which was a deep valley, and why they would refer to it as Shangri-La.

Devin: Right, it was a valley about 150 miles south west of Hollandia. And recently, military personnel had flown over this section of mountains — which is why they didn’t realize this valley existed, they normally avoided the mountains, but somehow they ended up flying through them — and there’s this valley below. And the immediate unique part that these pilots saw: they saw many villages.

Mitchell: Stories grew up around them in Hollandia, when someone would fly over Shangri-La, the valley. And stories tend to have this quality, they keep getting bigger the more times they get retold. These were huge, just giants. They grew pigs the size of ponies, and they practice human sacrifice and were cannibals — and only that last part was true. They were cannibals, but other than that they were actually a fairly diminutive people. Their pigs were normal sized. But the idea was that these were incredibly fierce warriors…and actually, that was true also. It says something about human nature that I guess I’ll leave to the anthropologists: despite living in a place where food was abundant, land was abundant, they had no disagreements about their belief system — the valley was in a constant state of warfare. They occupied themselves, in a way, by fighting.

Emma: And so naturally everybody’s curiosity was peaked, and they wanted to go and see it too.

Lauren: So on a Sunday afternoon, May 13, 1945 — which actually happened to be Mother’s Day — 24 servicemen and WACs got on a plane for a sightseeing mission into the Hidden Valley.

Mitchell: It was a pleasure trip. There was really nothing they were trying to accomplish, and I think that stuck with Margaret for the rest of her days.

Emma: It was a big C-47 transport. Margaret was sitting in the back of the plane, right next to soldier named Lieutenant John McCollom. It took 55 minutes to get to the top of that mountain, like about 10,000 feet up.

Devin: To make it to the valley, you basically had to fly between mountains and fly at a high enough altitude to actually be in the clouds, so you couldn’t really see your way in. What we know is that Margaret’s immediate boss, Colonel Peter Prossen, had flown to the valley before and knew the way in — but for whatever reason, he decided to hand over controls to his copilot, who had never flown into the valley.

Mitchell: He is talking with people and enjoying himself, and he left probably the hardest part of the flight to this much, much less experienced pilot, Major Nicholson. And even to this day, there are high winds, updrafts and downdrafts. It’s a fairly narrow pass. It was it was recommended, in fact, when the first flights were going into the valleys for the sightseeing trips — they were adamant: “Don’t have inexperienced pilots do this.” And that’s exactly what happened.

Devin: John McCollom, who was watching out the windshield — he was in the back of the plane, but he could see what the pilot was seeing — [he saw what] was essentially a mountain coming towards them. Nicholson pulls back, tries to gain altitude enough to avoid it and go over the top of the mountain, but he was unable to, and they flew directly into the side of a mountain, in the middle of the jungle.

Emma: Everything was almost like instant, it just exploded into a ball of flames. John, by some miracle, he wasn’t hurt at all. The back of the plane broke off, and he was able to crawl out, as did Margaret. And then there was another person that walked out, his name was Sergeant Kenneth Decker. Margaret was burned on her legs, very severely, and Decker had a wound on his head and was burned on his back. McCollom could hear voices in the plane, and so he went back to the plane, and he managed to bring two of the WACs out. But they were so badly burned, and where they were on that mountain, they said it rained all the time, especially at night. And so they covered themselves with tarps, and in the morning, when they got up, the girls had died. In fact, Margaret almost panicked, because she said, “Oh my God, oh my God, she’s dead!” And what she had to do was, Margaret’s shoes got blown off [during the crash], so she took the shoes off of her dead girlfriend, and she said she felt really terrible about it. I don’t know what John did [with the bodies]. I think he just covered the bodies with a tarp.

Lauren: It was tragic for all of them, but John McCollom’s twin brother actually was on the plane with him and died in the plane crash. So it’s hard for us to imagine what he would have been going through, not only the loss of his twin brother, but now trying to figure out how they were going to survive in the middle of a densely packed jungle.

Devin: He’s able to climb a tree and see that there is a clearing in the valley, and so he decides they need to make it there — because there’s no hope of rescue or even being seen when you’re in canopy jungle. And it’s not an easy trip. Two of them are severely injured, Margaret so bad that she has to crawl at some points. They find a dry riverbed, and that’s what they use to kind of get down this hill. At times though, there’s water in that, as it rains, and so they end up being in water and mud. It takes them several days to get down to the clearing, and once they’re there, that’s just the beginning of the story.

Lauren: John’s plan works: the rescue planes do come by, the survivors know that the plane has seen them because he tips his wing. And so at this point, they believe that there will be help coming back.

Devin: So what was this clearing that they found? Well, it was actually cultivated land by the natives who lived in the valley, the people of the Yali and Dani tribe. And they had a village very close by — in fact, it was a sweet potato patch that they were in. That first night that they were there, they are actually make contact with these people that they had never seen before.

Mitchell: The valley people were living, as I maybe mentioned earlier, really a Stone Age existence. They didn’t have the wheel. The men wore hollowed out gourds to cover their genitals, and they used bows and arrows to fight each other, and the bows were unflecked. They were living, literally, in another millennia from the people who had just landed in their world.

I talked to old men and women who were children when this happened. Sadly, I imagine they’re gone now, but 60 years later, these people, of course, still remembered. They recognized that these people — whatever they were, some of them didn’t even recognize them truly as people — but they didn’t look like their enemies. So the initial reaction was curiosity. Some of them thought they were gods or ghosts, because ghosts play an enormous part in the culture of the people of the valley. And so these light-skinned people wearing clothing were just such a mystery to them that they saw no immediate need to kill them. It’s remarkable. The initial thought was, if you knew all about the warlike culture of the people, you would think they’re going to slaughter these people — and they easily could have, especially when it was before the paratroopers arrived, and it was just Margaret, McCollom, and Decker.

Devin: So we have to realize it’s almost impossible to get out of this valley without walking 150 miles through the jungle. And obviously, with two severely injured people, and even a healthy person, that is a daunting task. So how would a rescue mission take place? You can fly over the valley with aircraft, but there are no helicopters or anything that could land easily. It’s a jungle — landing a full military aircraft, and the need for a runway and all of that, is just impossible. So the idea of rescue really comes down to one thing: parachuting people in.

Mitchell: Earl Walter and these Filipino American paratroopers were dropped in to protect the three and try to help them until they could figure out a plan to get out. I had the privilege of spending time with Earl at the end of his life, and Earl was amazing. He was this sort of strapping, 6-and-a-half-foot-tall guy who thought what he wanted was to get into battle, but his greatest mark in World War II was helping to keep alive these three plane crash survivors — along with the medics and the paratroopers he brought with him, this incredible group of Filipino American volunteers. They wanted to do anything possible, because both of their homelands had been invaded, and they wanted to be part of the war effort.

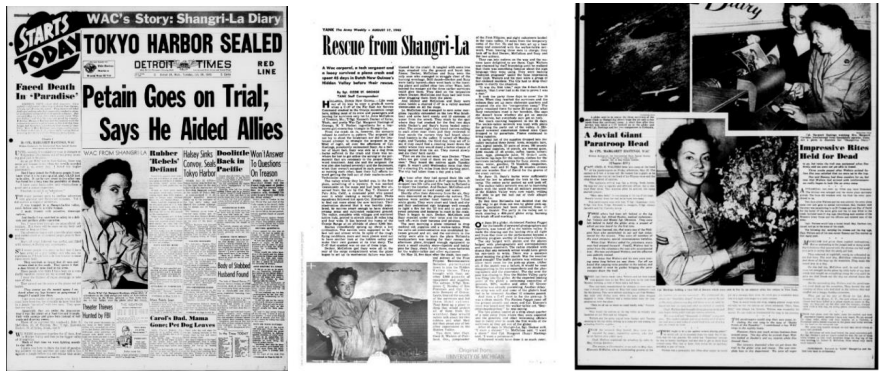

Lauren: By this point, news had gotten back to the U.S. about this horrific plane crash, and about the story of these three survivors that were stuck in this jungle.

Devin: The way this happened was there were two war correspondents, and they would take turns flying on supply missions to the valley to check in with [the survivors], and make sure everything was OK, and they would do that by radio. So the war correspondents road along, and they would take transcripts and ask questions of Margaret and the other people down there. And then they would go back and write up their stories and send them back to the U.S., and they were picked up by the Associated Press and in newspapers all around the country.

Lauren: There was a filmmaker named Alexander Cann, who was working for the Dutch government, who actually got up the courage to be dropped in on the ground with the survivors.

Emma: And he’s twirling ‘round and ‘round, and they go, “Oh my God, he’s gonna be killed.” Well, boom, he lands on the ground. They went over and they expected to see a dead man, but he wasn’t dead. He was dead drunk. He had taken so much whiskey to have the nerve to jump out of the plane. He took a ton of pictures and stuff like that of the natives. And that movie, you could probably find that on your computer.

Alexander Cann’s documentary on the crash: “Rescue from Shangri-La” is available for viewing on YouTube.

Lauren: I’m not sure how you make the decision, “OK, I’m going to bring my film equipment and I’m going to drop in, not knowing how you’re going to ever get out — because at this point, they still don’t know how they’re getting anyone out.

Devin: So how did they become rescued? It’s a plan that was developed in the military base at Hollandia by the officers there. And they were desperate, they thought of maybe sending troops over land, again, 150 miles through the jungle. They thought that is way too dangerous, we’re gonna end up losing several more people if we do it that way. So they were really racking their brains. And one of them came up with the idea of a glider. This had been done successfully in other places and used significantly in Europe, gliders. They were towed in by aircraft and then released, and they could fly silently and go great distances, depending on the weather and things like that. And they could carry troops, they could carry supplies. These were large gliders, these are not small gliders. The good thing about a glider is it doesn’t need an entire airstrip to be able to land and take off, like an aircraft would. But it still needs some sort of place to land — it can’t land in a jungle tree or a tropical forest or something like that. But they saw enough potential within the valley that they thought they could land a glider, and then the aircraft would let it go and circle back, and fly around the valley to allow for the glider to get ready.

Emma: They had to walk from the Hidden Valley, where they were in the beginning, over to the glider site, which was 40 miles away. Margaret said it took them three days or four days to get there or something. And the first day or two, Margaret said they had to stop every half hour to rest. As time went by she grew stronger, so she could walk for an hour and a half without stopping. God bless her.

Lauren: They lined what would essentially be an airstrip with bright-colored parachutes so that the pilot had something to look for. And then they had two upright timbers, kind of like a goalpost in football, and they stretched a nylon rope across those two uprights that was then attached to the glider. So once the rope was in place, and the glider was packed, the tow plane would come back, fly down really low – and there was a hook underneath that plane, and the hook would take hold of the nylon rope and pull up, and the glider would be pulled with that rope.

Emma: And you will imagine a C-47 transport plane that close to your head? They were really scared, not just because of the plane itself, but the noise, the roar of the engine. By accident, one of the parachutes that were lined the runway got hooked to the bottom of the glider. So Margaret said, “Jeez, as we were in the glider, we could hear the slap, slap, slapping on the bottom of a glider.” It started to tear the material on the outside of the glider, and she said at one point [they] could see the ground. “Wouldn’t it be something if after being in the jungle 47 days, we get killed being rescued? Being pulled up in the air?” But luckily, it held. I think it took more than an hour to get to the airport at Hollandia.

Devin: Now this is amazing in a lot of ways. First of all, it had never been done. Many things could have gone wrong. They could have crashed trying to get up through the mountains. They could have not had enough horsepower at that altitude to be able to take off once they did get a hold of the glider – if they got ahold of the glider. That was the other thing: could they actually connect the nylon rope to the grappling hook? So all these things could have gone wrong, but they didn’t.

Lauren: And once they were back, of course, this story was already all over the press. Margaret had actually kept a journal while she was in the valley for 47 days. And she gave this to the newspapers, and her journal was serialized, and it became a really popular story in America.

Emma: Every time she turned around, they were taking her picture.

Mitchell: Margaret was hailed as the “Queen of Shangri-La” when she came back to the United States. They put her on a bond tour – she was still a member of the Women’s Army Corps, and so she was paraded and she spoke raising money for the war effort. But she had very conflicted feelings about it, because as she was being celebrated, and as she was being put on display with camera people following her, she was really still dealing with the grief of the loss of all the people who had perished. Afterward, she returned to a very quiet life. She did marry, she had two children, and was an administrator at Griffiths Air Force Base. Once in a while reporters would reach out to her to ask her to tell the story, but she rarely revisited those days, except with her two fellow survivors – who also went on to successful, really good lives. John McCollom ended up becoming a surrogate father for his brother’s daughter, who never met her father. She just been born when her father died, so John McCollom stepped up and was a surrogate dad to her and a surrogate grandfather to her children. And Decker went on to a career in Boeing and a successful marriage. And then finally, their last public appearance together was at a reunion of World War II glider pilots, where they were hailed and from by all accounts, were very, very happy to be reunited there.

Emma: That was the last time she saw them. She died four years later from cancer. She was 64 years old, in 1974.

Lauren: In her later years, Margaret was asked how she survived, and one of the things she said was, “When you have no choice, you have no fear.” You just do what has to be done, and it is amazing that they were able to set aside this traumatic event that they had just been through and figure out a way to survive. And with the help of the Army, they were actually able to have a successful rescue mission and go on with the rest of their lives. The story does deserve recognition, and I found it really fascinating. And it’s so nice and refreshing to see a marker dedicated to a WAC like Margaret Hastings. It was such an amazing story.

Emma: During World War II, or any war, it’s always about men, of course. So when you have a female soldier, that makes your ears perk up. It was a world famous tragedy, so it wasn’t like just people in Owego knew Margaret – it was people all over the world. She had the foresight to record all of those things every day, she endured the physical pain of her burns. Her demeanor and her professionalism was noted by her commanding officers. They all wrote about how strong she was.

Mitchell: These three people showed tremendous fortitude, physical and emotional. They simply refused to surrender, and I think that’s a remarkable part of their story.

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.