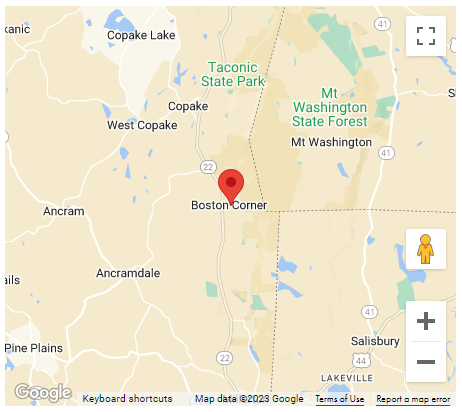

On this episode, Devin and Lauren tell the forgotten story of Boston Corners, which once belonged to Massachusetts, but was ceded to New York state by an act of Congress in 1855. The area, now part of the Town of Ancram, was remote in the mid-19th century and hard to access from Massachusetts, while New York officials had no jurisdiction there. As a result, it became a haven for illegal activity, including an illegal boxing match in 1853 that drew an estimated 3,000-5,000 spectators to an area with a population of 61.

Marker of Focus: Border Marker, Millerton, Columbia County

Guest: Rich Rosenzweig, screenwriter and professional drummer

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with help from intern Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby. This episode also includes sound effects from freesound.org (with no alterations), which you can find here and here. The main photo for this episode is a 1910 clip from the San Francisco Call, which you can find here.

Further Reading:

New England Historical Society, Boston Corners, The Naughty Town that Massachusetts Lost to New York

Arthur Myers, Sports Illustrated, The Brawls at Boston Corners

Patrick Higgins, About Town, The Battle of Boston Corners

Carole Owens, Berkshire Edge, The once-disputed Boston Corners was once too isolated to police

Clay Perry and John L. E. Pell, Hell’s Acres: A Historical Novel of the Wild East in the 50’s (1938)

Frank Baillargeon, Ambitions: The Life and Love of John Susannah Morrissey

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On today’s episode, we’re going to be discussing the backstory of a marker located in the town of Ancram, in Columbia County. This marker is located on Boston Corners Road and the text reads: “Border marker. Stone survey marker on this site determined southwest corner of Massachusetts, aka ‘Boston Corner,’ land ceded to New York State in 1855. William G. Pomeroy Foundation 2020.”

So what is the significance of a small, nondescript stone survey marker in a remote rural area? Well as the marker alludes to, this monument marks the current boundary between New York and Massachusetts. But it wasn’t always the boundary between these states, it boils down to more of a geographical problem than anything else. In the 18th century, when surveyors were laying out the boundaries for towns and counties – and states, in this case – they often used geological features such as waterways or mountains to determine those lines. This is most likely the case in the area of these two states. The Taconic mountains run roughly north to south, and they seem like a natural boundary between this part of New York and Massachusetts; except for in this small area, where they take a turn to the south east, creating a triangle of land that is very difficult to access from the Massachusetts side, due to Mount Washington being a pretty formidable obstacle. However, it was much easier to access from the west, which meant that in the early 1800s, European settlers were coming into the area, mostly for agricultural use, and the small hamlet became known as Boston Corners.

Now, Devin, I didn’t come across anything in my research that mentioned specifically why it was called “Boston Corner” or “Boston Corners,” did you see anything?

Devin: No, I actually think the terms are used interchangeably. I had no idea about any of this story of Boston Corner; I didn’t know it’s kind of sordid history, but it was really through one of our listeners, who happens to be a colleague of mine at the State Museum, that I became aware of this story, and she mentioned that her brother-in-law, Rich Rosenzweig, is working on a screenplay about this place called Boston Corners.

Rich: I’m a professional, busy drummer in New York City. Most of the screenplays I’d written were quirky, indie-type films. But because I had been spending time visiting my brother, who lived in Copake at the time, introducing him to friends who live in the town of Boston Corners, and then telling me, “You need to know about this town,” showing me the historical marker for the boxing match. That led to learning about the interesting history about that town back in the 1850s. The boxing match itself, and subsequently, the cult novel that was based on this story written in 1938, called Hell’s Acres, of which there was a mimeograph copy in the local library, and otherwise very hard to find. It was the perfect makings of a great feature film.

Devin: To get a sense of what Boston Corners was like in the 19th century, one of the best sources is the history of Columbia County, which was written by Franklin Ellis and published in 1878. And here’s what he says, “Boston Corners is a small hamlet, it contains one hotel, one store, one blacksmith shop, a fine depot, and about a dozen dwellings.”

Rich: That’s about 1000 acres. And it was officially part of Massachusetts because of the way they drew the line. But it was impossible to get to the rest of Massachusetts from this patch of land because the mountains were very high and to get to the rest of the state by a horse would have taken a full day or more. Because it was ignored by the rest of the state, taxes weren’t collected there; they were fine with that. They didn’t bother to vote. And it was pretty sleepy.

But part of that separation meant that they had no law enforcement. And the way law enforcement was back then, jurisdiction was extremely important and very technical, so that once you stepped across the border – from New York State or Connecticut – into Boston Corners, you couldn’t be touched by the law. And when word got out to fugitives and questionable types that it was a place you can hide from the law, the people in the town started to notice that all these undesirables would come and stay for a while and then leave.

Lauren: What really began to transform the community close to the middle part of the 1800s was when railroads started to come into the picture. And these were railroads on the New York side, which made the town much more accessible to larger numbers of people.

Rich: Word got out more and more. Just north of Boston Corners in the town of Copake was a hastily-built place called The Black Grocery, which was created to blow off steam. You could buy groceries, but it was also a saloon. A lot of activity went there, you could probably buy a girl to dance with and do whatever else you might want. Duelists would come. I read one account, a couple of carriages came through, they stepped over the border, there was a pistol duel, someone would get shot, maybe killed, they’d throw the body on the cart and leave. And these local farmers were thinking, you know, “What the hell is this?”

By the late 1840s, these folks were pretty upset, and they begged Massachusetts to let them go. Didn’t take long; by mid-1852, Massachusetts made it official for them. A few months later New York State accepted Boston Corners, but it needed to be made official by the federal government. And there was a lot of red tape. It was an insignificant little dot on the map, and the administration of President Franklin Pierce was not really going to pay much attention. So, from late 1852, until early 1855, Boston Corners belonged to no state.

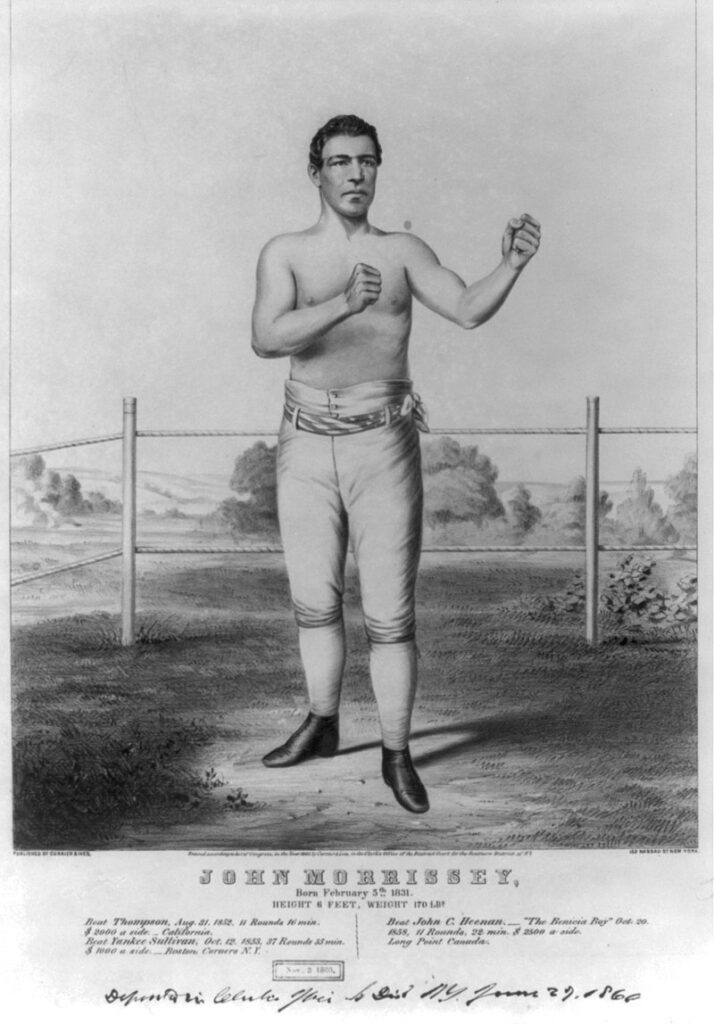

Devin: All right, there was a major boxing match that took place in Boston Corners in 1853, to be exact, between two Irish American immigrants: John Morrissey, who grew up in Troy, and Yankee Sullivan, who grew up in New York City. Both of whom were not only prize fighters, but were also at least gang members or gang affiliated; we have to think about the era that we’re talking about with the influx of immigration, specifically Irish immigrants, flooding into New York City and New York State, many of whom are struggling economically, and were facing off against prejudice when they would arrive here as being Irish and being Catholic for the most part. So they would find themselves in desperate straits many times, and many of them turned to petty crime or even violent crime.

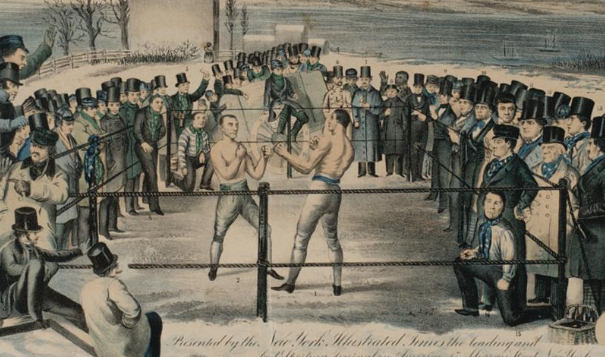

And we have to think about boxing in the 19th century too. It’s not the type of fighting that we think about today, when we think about boxing and gloves and rings and all of that. It was really a brutal sport, it was bare-knuckle. There really weren’t very many rules right up until the year before the Morrissey/Yankee Sullivan fight, when the rules were changed under what was called the New London rules, as opposed to the Old London Rules. So there was: no head butting, no gouging, no kicking, no hitting below the waist. So it was slightly less barbaric, perhaps than the Old London Rules, but it was certainly still a violent sport. The fighters would fight until one of them could not go on, or until people in their corner called the fight on their behalf. One of the aspects of the New London Rules was this idea that the rounds would end as soon as someone’s knee touched the ground. So if one of the fighters was hit and fell to his knees, or fell to the ground, the round would be over – not necessarily the match – if he could get back up and continue on he would, but the round would be over and this would play a key role in the Sullivan/Morrissey flight.

Rich: Yes, boxing was illegal. These matches, they were still extremely popular. It was covered by the news regularly. Newspapers would start their accounts by saying “this disgusting sport,” and then proceed to describe what happens in the fight round-by-round. And the fights would be held in out-of-the-way places so that the cops couldn’t break it up. They were fought on piers, on islands. The big championship fight before the fight in Boston Corners was between Yankee Sullivan and the champ named Tom Hyer, and it was held on an island in front of about 200 people, after it had to move from another location.

He actually lost to the champ, but Tom Hyer retired temporarily and Yankee Sullivan was able to claim himself to be the default champion. Now we find him five years later, being sought after, and challenged by John Morrissey, the challenger. And it’s important to note the difference in these two fighters. Yankee Sullivan at the time was 41 years old, hadn’t fought in five years, was between 5’ 9”, 5′ 10” – I think he’s actually 5’ 9” – and weighed about 155 pounds at the most. John Morrissey, he was a big brawler, as opposed to Yankee Sullivan, who might not have been as skilled a boxer but was really difficult to knock down, and he challenged people constantly. He challenged the real-life version of who Daniel Day-Lewis played in Gangs of New York, a man named William Poole who was a boxer and bigoted nativist. But what he sought most of all, in the early 1850s into 1853, was to fight Yankee Sullivan for the championship.

OK, so to set the scene, what wound up being several thousand – mostly men, lots of gang members – were arriving in Boston Corners, mostly by train. The train station that went through Boston Corners went right by where the side of the fight was, which was in this beautiful sloping field.

Devin: So, we actually have a first-hand account of what happened during the fight in 1853, and it was an interview with a man named Harm Miller, and was published in 1905 in the Millerton Telegraph newspaper. Well, Harm Miller was a young boy during the 1853 fight, and he really sets the stage for us by showing us in this interview that the locals really had no idea that this was happening. He only found out because the day before, people started showing up and he called them “toughs”, because the majority of the audience were affiliated gang members from the Five Points area of New York City. These were the people who backed the fighters. These were the people who bet on the fight. They showed up by the thousands; estimates ranged between three and five thousand. And we’re talking about a hamlet with eleven houses and, you know, a depot and a hotel and not much else. He goes on to describe some of the illicit activity they were into.

Lauren: The kids were? Or the thieves? Like the criminals?

Devin: No, the thieves! “Mrs. Fretts had a lot of loaves of bread sitting in the pantry window to cool – some fellers saw it and they swiped the whole batch. She asked them to leave her one loaf for Morrissey who was putting up there, but they swore at her and told her no! I saw a feller put his hand in High Roger’s and pick out High’s pocketbook. High felt him but it was done so quick the feller got away… I saw another tough snatch ‘Hod’ Silvernails’ watch and they stole a hundred dollars from Pete Bashford. They stole every chicken they could see… They broke open the schoolhouse and cooked their plunder there.”

It was like a riot, even before the fight!

Rich: The trees were filled with young boys who climbed up to watch the fight. It was actually quite formal. A referee was chosen whose name was Charlie Alair. Each fighter had his seconds, who were usually two corner men, and each fighter had their own umpire, or umpires, who would be outside of their corner to make sure that the referee was calling the fight fairly. And I did, after some research, because of the incredible feud between young John Morrissey and Bill the Butcher (William Poole), which was a huge deal in New York City at the time, I knew that he had to be attending the fight and sure enough, he was an umpire for Yankee Sullivan.

Each fighter would come into the ring and throw their cap, or throw their hat into the ring. Then the ref would begin the fight by calling them to the scratch line in the center of the ring. The witnesses describe it as: “suddenly, it all became silent.” The fight begins with 100 to 80 that Yankee Sullivan was going to have the crap beaten out of him because of his age and his size. And very quickly, what all the people see is that this guy is a skilled boxer, and he’s taking advantage of the New London Rules, and what he does is he pummels young John Morrissey with a few blows to the face and then immediately – deliberately – falls to one knee and ends the round. The difference was that there was no bell.

John Morrissey is left stunned, not knowing what to do, and this happens for round after round. And after ten rounds or so, Yankee Sullivan is clearly out-boxing young John Morrissey. But – though he’s really beaten really badly, and many of the journalists are describing his face as just cut open, bleeding; they don’t know how he can go on… he manages to come out and continue fighting. And this goes on for 55 minutes. Round 37 is called. And by the way, because so many of the spectators were not that aware of these new rules, and they’re wondering why Yankee Sullivan who – by the way, the odds had switched 100 to 50 that Yankee Sullivan would win – but they’re wondering this strategy where he comes out, hits John Morrissey, and then falls to a knee in the rounds over.

So by the 37th round, Charlie Alair calls the fighters out, and after a few hits John Morrissey grabs Yankee Sullivan by the neck, and as far as the journalists could see, he lifts him up, throws him against the ropes. And he’s choking Yankee Sullivan! The seconds are screaming “Foul!”, and there’s a scuffle where both fighters are fighting with other people. And as far as the journalists could tell, Yankee Sullivan winds up out of the ring, rolling around fighting with one of John Morrissey’s seconds. And people are screaming at Charlie Alair to call them to scratch. And John Morrissey manages to make it out to scratch – probably dragged out. Because of the rules. Charlie Alair has to call John Morrissey the winner. And this was after an hour and 37 rounds of them watching, kind of miraculously, this old man beat the crap out of young John Morrissey and the odds changed, all the money – where the bets have changed – and now they hear that John Morrissey is declared the winner.

At that point, Yankee Sullivan runs back into the ring and starts screaming after him as they drag John Morissey out, “Come back and fight! Come back and fight!” And the crowds are so freaked out that once the fighters are hauled away – and by the way, they both spent the night in jail – the crowds ransack Boston Corners, and even as they head into the new little village of Millerton, New York, they ransack that village.

And that’s it. The newspapers come out the next day with John Morrissey is the new champion boxer. And then there’s an epilogue for both guys.

Lauren: They were celebrities. The boxers of, you know, the mid-19 century, late 19th century. They were the sporting celebrities of the day. So these names: Yankee Sullivan and John Morrissey, whose nickname was Old Smoke, reportedly because he was fighting and he got knocked over into a coal stove and his back was smoking and he stood up and continued the fight. So John Morrissey and Yankee Sullivan were household names and they became famous.

Before we started researching this episode, just like you Devin, I had never heard of Boston Corners, I didn’t know the story about the price fight. But I have to say I’m not terribly surprised to hear the name John Morrissey pop up among the names of prize fighters at this time. Morrissey is inextricably linked to the history of Saratoga Springs because he’s one of the founders of horse racing – organized horse racing – in Saratoga Springs, and of course, the builder of what we now call Canfield Casino, but he built it at the Clubhouse. Not to be confused with the Racino, you know where gambling still takes place today, but with the Canfield Casino that’s located in Congress Park, which is now the home of the Saratoga Springs History Museum on Broadway.

So let’s just back up a little bit and talk about who John Morrissey was because he really is a fascinating character. He was born in Ireland and his parents immigrated to America when he was a very young boy. The family settled in Troy in the early 1830s, which was a place that numerous Irish immigrants were settling at the time, because it was a growing industrial city, and there were lots of places to find work, both skilled and unskilled labor. He began street fighting and gambling at a young age and he would have been exposed to that; there was a lot of Irish immigrants who were paid a very low wage, and there would have been a lot of territorial disputes. There were gangs in Troy at the time, he was probably exposed to that. So he didn’t have an easy childhood. But all of the things that seem to define him later in life happened very young when he was still living in Troy.

After the fight that he won at Boston Corners, he did continue to fight. There was one more, another wildly famous fight that took place in 1858, against John Heenan that he won so he was able to maintain his title of champion. After that, he really began to focus more on his career in politics in New York City. And this is the time when Tammany Hall was very powerful; Boss Tweed. It appears as though he was aligned with Boss Tweed at first and then later on, he was anti-Tammany Hall in the 1860s was when he first started coming to Saratoga Springs. And of course, this is the time when it was a very popular resort community in the summer months, there was a lot of wealth there. And I’m sure Morrissey saw an opportunity to make money. Very shortly afterwards, he invested close to – at the time – $200,000 to build what he called The Clubhouse. It was a very swank upscale place where the wealthiest visitors to Saratoga could come and gamble, and that’s where he made his name in Saratoga Springs.

Now the other claim to fame that Morrissey has, of course, in Saratoga Springs is the start of organized horse racing. And in 1863, he and some other men started what is believed to be the first organized horse race, which we say is the beginning of the Saratoga Race Track. He was actually elected to serve in the House of Representatives in 1866. And again in 1868, which is really remarkable. He was in his 30s at the time, and you know, he came from an immigrant background in Troy, New York. And by the time he’s in his 30s, he’s a household name. He’s well-known enough to serve in the House of Representatives. He was later elected as a state senator from New York in 1875, and then he was reelected in 1877, but unfortunately, he did not get to finish that term. He died of pneumonia on May 1 in 1878. He actually died on the second floor of the Adelphi Hotel, which is on Broadway, it’s still there today. And he was only 47 years old.

Reportedly 20,000 people came to his funeral in Troy, he was so well-known. Flags flew at half-staff because – a state senator at the time, and it was one of the largest funerals ever held in the city of Troy.

Devin: Yes, John Morrissey’s legacy is quite a bit different than his opponent, Yankee Sullivan.

Rich: Yankee Sullivan didn’t fight again. He stayed involved in gangs but wound up in San Francisco, where he was arrested and thrown in jail. And because he had some big problems with rival gangs, as he awaited trial, he was found with his wrists slit, and it was officially declared a suicide, but most people thought that his wrists were slit for him and he died, I think about a year or so after the fight, never having fought again. And um, a bit of a footnote.

Lauren: It kind of struck me that there are a couple of different terms that are in our vocabulary today that came from boxing, the first of which is “toe the line.” So there was a line scratched in the middle of whatever served as the ring. And when it was time to start the next round, both boxers had to come up and toe the line, which meant that they were able to fight for the next round. The other phrase that we use is “throw your hat in the ring.” If someone was ready to challenge a fighter, the notification would be to take off your cap and throw it in the ring, and that alerted the referee to the fact that you were ready to fight your opponent. And those are things that, you know, people still say today, but it speaks to the popularity of boxing. If everybody knew what these terms were, what they meant, then, you know, that’s how it kind of seeps into everyday vocabulary.

Devin: So Lauren, you and I are historians, we specialize in New York State; neither one of us had heard of this story, even though there were such iconic characters, including John Morrissey and Yankee Sullivan and the Five Points gangs from New York City and on and on. Why is it that something like this would kind of fall through the cracks and be something that we didn’t know anything about, and maybe not too many people outside of the region would have known about either?

Lauren: I think this happens a lot in history, that these kinds of events that are monumental to a community, they’re huge for a little while and then they start to fade. But then you see things like the account that you read that comes to light 50 years afterwards and then you see some other people that start to recollect these and write it down, which is the case with Boston Corners. In 1938, a novel came out called Hell’s Acres, which is a somewhat fictionalized account of this community of Boston Corners, of the problems that they had, it includes the fight. And it’s this wonderful novel, but it’s nearly impossible to get now. And the reason that it’s nearly impossible to get is because the people of Boston Corners didn’t want to be known just for this one illegal fight that took place here. And so when the novel came out – even though it’s a great story, it could have been very popular – they tried to quash it by buying up all the books so that it didn’t become larger than Boston Corners itself.

Devin: It’s about historical memory. But it’s about what a community wants to be remembered for, too. And at the time, at least, that Hell’s Acres came out, I think the community had moved on from being known as Hell’s Acres, or, as Ellis said, “a city of refuge for criminals and outlaws of all classes.” Instead, we have things like the 2002 Martin Scorsese film, Gangs of New York, which mentioned a lot of these characters. Again: a fictionalized account, but it mentioned a lot of the characters in the Five Points and a lot of the gangs that were actually involved in this fight in Boston Corners. And that’s kind of the history that we think of, and that’s the story that we know. It’s a city story, it’s an urban story… it’s not a story about this rural Hamlet, in Columbia County.

Lauren: Having said that, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t room for someone to come along and take this story, look at it from a fresh perspective, and turn it into a modern story that we’re interested in today.

Rich: So if I were to put this story forward, what I did for a modern audience was I made it much grittier. And also, it had a – well I don’t want to give away the ending, actually! But I changed the ending a bit so that it felt more realistic. And, yeah, I’ve been shopping it around, I’ve done readings of it. Really, I have to say for me, anybody who loves history, to be in that quiet little area, and try to imagine where you’re standing. In some ways, it hasn’t changed much and in other ways it has. But it continues to be such a fun and interesting thing to imagine little Boston Corners and what happened just for a few days in 1853, and what they went through for a year and a half belonging to no state and what they went through for several years just being this weird, out-of-the-way anomaly.

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with help from intern Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.