On this episode, Devin and Lauren discuss a William G. Pomeroy marker recognizing a 1900 auto race in Suffolk County, New York, and the importance of racing in automobile history. Was that race to Babylon really the first of its kind in the U.S.? And how did Watkins Glen International get its start?

Marker of Focus: Auto Race, Babylon, Suffolk County

Guests: Mary Cascone, Town of Babylon historian; Steve Loughman, historian and curator at the New York State Museum

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

American Auto Racing: The Milestones and Personalities of a Century of Speed, J. A. Martin and Thomas F. Saal (2004)

Smithsonian article on Andrew Riker

Smithsonian article on the 1908 New York to Paris Auto Race

Teacher Resources:

PBS Learning Media video: Motor Racing Research Library

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

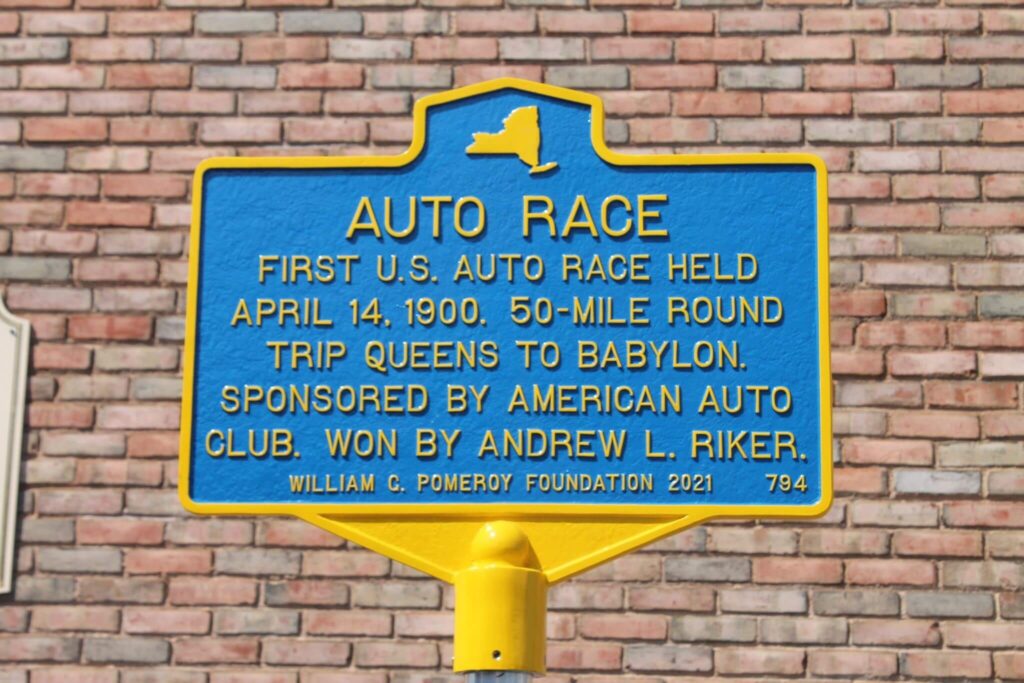

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. Today we’re focusing on early auto racing in New York, which brings us to a marker located on West Main Street in the village of Babylon, which is in Suffolk County out on Long Island. The title of the marker is “Auto Race” and the text reads: “First auto race held April 14, 1900. 50-mile round-trip, Queens to Babylon. Sponsored by American Auto Club. Won by Andrew L. Riker. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2021.”

So Devin, I grew up in Fulton County, and during the summers, Friday night racing was a big deal. Within an hour of where I lived, there were two different tracks. We had Fonda Speedway and Malta Speedway, both of which are still active. And I can remember going to the races with my dad and my brother, and there were big crowds, and it was really exciting. Did you have dirt tracks?

Devin: Yeah, yeah. So where I grew up, I didn’t grow up too awful far from Watkins Glen International, which is, of course, the NASCAR site in New York State. And racing was huge. Drag Racing, dirt track racing, demolition derbies – which aren’t really racing, but it’s a motorsport, I would say. I do think that it’s something that attracts millions of people as spectators, but it’s also something that goes beyond NASCAR. We all know about NASCAR, it’s on TV. Formula One is on TV. These are major sporting events, but there is also this kind of grassroots network of tracks where I think more people have a direct attachment to the sport.

Lauren: So let’s take a look back at the origins of early auto racing in New York. The marker that we just referenced talks about a race that took place on April 14, 1900. It was a 50-mile out-and-back race. They left from Queens, went all the way out to the village of Babylon, where there was a turn around that was marked by some barrels in the street, and then they came back, and the finish line was also at Queens. There were originally 15 participants signed up for the race. In order to be a driver, you had to be a member of the American Auto Club, that’s who sponsored the race. Actually, only nine of the 15 cars were at the start of the race, and seven of them completed the race. There were notably three different kinds of cars: gasoline-powered, steam-powered, and one electric-powered car. To tell us more about the race, we contacted Mary Cascone, who is the town historian in Babylon. And she helped to give us some more details.

Mary: We were the countryside for New York City. We have many small villages with railroad stations, but wide open spaces of fresh country and seaside air in between them. The route was generally referred to as Merrick Road. This is a road that starts as American Boulevard in Queens, and then it becomes Merrick Road in Nassau County. And when you cross into Suffolk County – it’s still Merrick Road – and Amityville, but then it becomes Montauk Highway. And then you get into Babylon, and it’s called Main Street. One road, many names.

It doesn’t seem that there were as many people who watched the race in Babylon as we’re surprised that the race was coming through. This was very heavily publicized in the Brooklyn papers, which would have come out every day. But the local papers here out in Suffolk County would have only been once a week, and if that local farmer missed the piece that this thing was going to be coming by…it seems more that people were surprised about it. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, whoever that reporter was, we have to thank them, because they described it: “Fortunately the day passed off nicely, without any accidents more serious than bursts of unprintable opinions from the Long Island farmers.” The newspaper described that a farmer was resting in his wagon after his morning work, and when the race started to pass him, his horses tried to “climb into the wagon with him, and all because of some enthusiastic chauffeur.” “Some swore under their breath. Some swore over their breaths. Nearly all swore, and a few, having exhausted the English vocabulary, became inventors.” Apparently the wind on the return trip hindered many drivers, particularly those with steam engines. The race was won by Andrew L. Riker, who drove an electric car for two hours and three seconds with no stops. He finished 15 minutes ahead of his competitors.

Lauren: One of the aspects discussed frequently in the papers is the anticipation over what type of automobile was going to win the race.

Devin: We have to remember that in the late 19th Century, early 20th Century, steam power was kind of the tried and true method for getting around, with trains and steam boats. But it had a lot of issues. Number one, you have to keep adding water. Also, the amount of time it would take steam-powered engines to warm up, to be going fast enough internally to be able to propel the car forward, could take up to 45 minutes on a cold day. Among the first electric cars created in this country was in Des Moines, Iowa by a chemist named William Morrison in 1890. Around that same time, the internal combustion engine, which had been around since at least the early 19th Century, was being perfected as a technology as well, and by the late 19th Century, gas-powered automobiles were starting to be introduced. Now, they had issues too. This is the era of the hand crank. They also were quite loud, much louder than the other two. The exhaust was very unpleasant, and there was a lack of gas stations, so acquiring gasoline was difficult in some places. At the end of the day, you start thinking about the electric car, and you start realizing that the electric car is quieter, as powerful, if not more powerful, and it’s also rechargeable. By the early 20th Century, New York City had a fleet of up to 60 electric taxis. So what happened?

Well, a variety of things happened. Number one, we have to remember in the late 19th Century, early 20th Century – very few places actually had electricity. The farther away you get from those urban areas, there would be less chance of electricity existing, therefore you wouldn’t be able to charge your car. Also, by 1908, when the Model T Ford was introduced, it was a gasoline car, it was easier to produce, cheaper to produce, and it was mass produced by Henry Ford. And in 1912, another important invention came forward that allowed gas-powered cars to become more viable, and that was the introduction of the electric starter. So by 1912, your Model Ts and other automobiles that were gas-powered, you didn’t have to hand-crank them. Electric starters are easier for everybody, and by the 1920s gas stations were popping up around the nation. So again, the fuel source was more accessible. So for all these reasons, the gasoline-powered cars become the dominant car, and electrical cars fade away…at least for now.

Lauren: It’s interesting that this race has all three of those types of cars, but only one electric. Because of the length of the race, which was 50 miles, they didn’t know if they would be able to be powered throughout the whole race. And some of the articles in the newspaper speculate that if it was a shorter race, we would be betting on the steam-powered cars, because they could go faster for shorter intervals. But because they had to stop for water at these longer races, it takes precious minutes to stop – and also for the effect of the wind on them, right? Weather affects these steam powered cars more than the others. One of the things they mentioned about the electric car in this race is that it’s kind of aerodynamic compared to the other cars. It sat lower to the ground, it had a compact feel to it. Andrew Riker and his electric car was 15 minutes ahead of the car in second place.

Devin: Now this marker notes, and many of the articles and newspapers that came out at the time suggest, that this was the first auto race in the United States. Now that’s somewhat of a controversial claim. I sat down with historian and curator Steve Loughman to talk about whether or not this actually was the first race in the country – or even if it was the first race in the state.

Steve: So the first automobile race was in France in 1894, and a year later in 1895 is what’s considered the first automobile race in the United States – and that was in Chicago. They actually had to cut the distance down from that race, because the day of the race there was eight inches of snow. The first automobile race in New York, or what’s considered the first automobile race in New York, was in 1896. It started in New York City, and then it went to the Ardsley Country Club in Irvington, New York.

Mary: This idea about being first, I suspect that it had to do with the formal organization of the Automobile Club of America. Several of the articles referred to the French Automobile Club, and I get the impression that the American club wants to start showing some entry into the fields. There were automobile manufacturers racing their cars prior to 1900, at least the automobile manufacturers, to be certain. But those were industry rather than amateurs and enthusiasts. So I do start to wonder if, you know, ACA, your Automobile Club of America, if they just had a really great PR firm and got all this information out there. As municipal historians, you know, we have people that will come to us and say, “Hey, highlight this thing about our community.” And sometimes we find out that the story got lost along the way, and that we weren’t the first but we were among the first.

Lauren: It seems that we always put a lot of importance on whatever the topic is being “the first.” Being the first legitimizes whatever you’re talking about. In this case, we have numerous newspaper articles that are contemporaneous to the race claiming that this race is the first auto race. It’s pretty clear that it wasn’t. Now whether there’s qualifiers to “the first race” – so maybe this was the first 50-mile race, maybe this was the first sanctioned race, because it was sponsored by the Automobile Club of America – those are all things that might distinguish it from the previous races that Steve talked about. So I think there are lots of different ways to look at this, rather than being incorrect. It may just be a different type of “first auto race.”

Even though automobile racing was really popular, there were still some holdouts that thought this was not going to be the wave of the future. In a newspaper article just after the race, there’s a local who’s talking to the reporter, and here’s what he says: “As I watched the automobile speed along over the south road the other day, I thought, ‘As wonderful as they are, I would not exchange a fleet-footed, reliable, intelligent horse for one.’ An automobile will not shy away at a sheet of paper and bolt, it’s true. But on the other hand, it will not whinny a welcome to its owner as he enters its stable…There may be pleasure in driving an automobile at as high a speed as electricity, gasoline or steam can propel it, but it does not seem to me that the pleasure thus derived can possibly equal the joy that comes to every genuine horse lover, as he drives his favorite horse at his best speed.”

I don’t know about you, Devin, but when I turned 16, I had a car, and I named it and thought of it as a pet. I don’t know, I know there’s other people who have names for their cars and they deck them out. It kind of just reminded me of how we have personalized our cars now in a way that, you know, maybe people thought of their horses as their companions. Now we have this kind of special relationship with our cars.

Devin: One of the things that may have caused this particular person to be a little reluctant to jump fully into the world of automobiles was their incredible cost at the time. Owning an automobile, and certainly racing an automobile, was really a rich person’s game. Certainly by the time Henry Ford perfects the assembly line method, and prices of the Model T continue to go down, and they become more usable and more accessible to people, then more people become involved with them and start seeing the benefits. But it takes a lot of time for racing to become something that is available and accessible to your average person.

Lauren: Also notably missing from the early auto racing scene are women. But along with the development of technology, you also see the inclusion of women learning how to drive and maybe treating the convenience of an automobile in a different way than these early racers are treating it.

Mary: Women were driving, we do know this. A month before the race, the Women’s Home Companion announced that there were at least two dozen women drivers in New York City. And the article specifically highlighted two groups of women: women physicians who were using automobiles to transport patients, and female kindergarten teachers transporting students to and from school. So I have to applaud our foremothers for jumping on the practical bandwagon with ambulances and school buses, even if they didn’t join the auto races. I did find in 1900, in relation to women and motoring, that since motoring was a sport it also had its fashion – and women’s automobile coats were advertised that year. So we know that they’re riding in the car, if they’re going to have their automobile coat on. And I have pictures from, locally, when a family got a car, that the daughters were actively learning how to drive and taking them around the streets.

I think that it has a lot to do with the way that things are reported. For example, I have a lot of instances where people will say, “Mr. Smith owned this piece of property.” And when we actually go to the documentation, it turns out that Mrs. Smith owned it, but she was never given credit for it. So I think that there is definitely some gender bias that happened in the reporting from that time period, where even if there were women owners, women supporters, they just were kind of left out.

Lauren: So when did international races start?

Devin: Well, among the earliest was the Peking-to-Paris competition in 1907, but arguably the most impressive was the 1908, 22,000-mile New York-to-Paris race. Many of these early races were sponsored by publications and newspapers, magazines, and they were created really as a publicity stunt. It was a built in a way to engage readership on a daily basis, because every day, they would have an update from the road, saying “This is where that racers are now, and this is what’s happening.” So people were very interested. We have to remember that racing as a spectator sport, directly, didn’t really exist [yet]. Because there weren’t racetracks – all of these races were taking place on whatever rudimentary roads existed at the time – there would be a lot of people at the beginning of a race, and there would be a lot of people at the end of the race, and in between people would get their information about the race through the newspapers. So the New York-to-Paris race was co-sponsored by the French newspaper Lamartine and the New York Times. All of the cars were gas-powered at this point. And the planners of this New York-to-Paris race determined that the best time to leave New York City would be the dead of winter. And why was this the case? Well, their original idea was to have the racers go up the Hudson Valley and across New York state, and then across the entire continent of the United States until reaching the West Coast. Then, the idea was for the cars to be floated to the coast of Alaska. They would then drive across Alaska, which had absolutely no roads at the time, and reach the Bering Strait, which they hoped would be frozen since it was winter. They would drive across the Bering Strait into Siberia, which also had no roads, drive across Siberia, and into Europe, into Berlin and eventually to Paris.

Steve: That did not happen, because when the first car got to Alaska they realized that there was no way we were going to drive across the Bering Strait. Only one car made it to Alaska. That car got shipped to San Francisco, and the competitors went from San Francisco to Japan, to Russia, and the race finished in the summer in Paris. There were only three cars that finished. The lone American team, which was the Thomas Flyer – Thomas Motorcars was based out of Buffalo, New York – that car actually didn’t get to Paris first. There was a German team that arrived to Paris first, but they had been given a 30-day penalty because their car had been shipped by rail in some point across the United States, and their car had also bypassed the Japanese leg of the event. So they arrived in Paris first, but then four days later the Thomas Flyer entered Paris, and they were deemed the winners. The third car that finished was an Italian team, and they arrived in September. So they arrived months after the first two cars arrived.

It was a miserable experience. You know, they were going across places that had no roads. Driving across Siberia and Russia in early spring, during mud season, they weren’t even counting the days by how many miles they completed – it was by how many feet they were able to move the car. There was a lot of community effort. The car would enter your town, and the people would help you kind of get your car across to the next place. So it was really a brutal affair, and these cars would have no rooves – they were very simple machines. Tires were not treaded at this point. It was a real test of men in machinery at that point.

Devin: As racing became more of a spectator sport, there was a quick realization that racing was not only dangerous for those who participated in the race, but also dangerous for the spectators. For example, the New York State Fair and Syracuse began holding races in 1903. It built its own dirt track, it enabled spectators to be very close to the track. In many cases, during the early races, the crowd wasn’t even in the grandstand – they were just standing as close as they could get. And there started to become a series of accidents that were very traumatic, the worst being in 1911, which at the time was actually the worst racing disaster in the nation’s history. And that’s when a race car went off the track, into the crowd, and killed 11 people. That caused Governor Dix at the time to actually ban racing at the State Fair for 10 years. And even after that, there were instances in the 1920s and 30s and 40s and 50s, of accidents happening that not only would unfortunately kill the driver, but sometimes injure people in the crowd, as the vehicles would careen off [the track], or pieces would fly off, and things like that. So it was a very dangerous sport. It still is a very dangerous sport. Safety has increased many times, both for the driver and for the audience. Now there’s barricades, there’s fencing, grandstands are farther back, it’s less common and less possible for spectator injuries to take place. But it’s still a very dangerous sport for the driver.

Lauren: And I’m guessing the reason these tracks started to be built was because of the danger of having them on actual public roads. Second, being that you could have more spectators if it was a shorter track that was in an enclosed area.

Devin: I think you make a good point. And we see this in Watkins Glen, which is the speedway that I grew up nearest. And that race, which is world famous to this day, started as a road race going through the village and in the county roads. Over time, it was determined that was problematic, and there was a speedway built as a road course – so to mimic what a road course would be, not just an oval track. It’s a track that has straightaways and curves, and it’s very difficult track. But they built the Speedway in 1956, and it hosted its first race in 1957 as a way to make it safer, make it easier for spectators, and make it easier and better for drivers as well.

Steve: So 1948, Cameron Argetsinger, who was a lawyer, he had this idea to bring international racing to the United States into Watkins Glen. The local community was looking for a way to extend the vacation season. Watkins Glen’s a very picturesque Finger Lakes town, it’s beautiful in the summer, but the reason that the first races were in the fall was that it extended the vacation season. This was really a rebirth of road racing after World War II. After 1948, we started to see road racing go all over the country: races in Bridgehampton on Long Island, Lime Rock in Connecticut, Elkhart Lake in Wisconsin, we start to see the West Coast Laguna Seca and Monterey. A lot of other places. Those are racetracks that are still around today, but there were a lot of other races all over the place, all over the United States – and Watkins Glen was really at the forefront, and they were one of the more organized events. They were the ones that drew international competition back to the United States, and they hosted the United States Grand Prix Formula One from the early 1960s up until 1980.

The racetrack was a success considerably, but financially during the 70s, there were issues with the race track. Crowds were unruly. Also, in 1973, the racetrack held a concert, and that concert was bigger than Woodstock. I think the townspeople kind of soured, and by 1980, the race track was closed. And then in 1983, Corning Glassworks was looking to get into NASCAR, and they were told by NASCAR that, “You guys should look into Watkins Glen, that’s right in your area. Maybe that would be an avenue for you guys to get involved in racing.” So Corning Glass and the International Speedway Corporation, which is the company through NASCAR that operates the race tracks, they began a partnership to revitalize the racetrack. And since then, it’s been a rebirth of racing at Watkins Glen. It’s one of the biggest events on the NASCAR calendar. NASCAR is, in America, that’s the top echelon of motorsports. It’s definitely one that brings in the most money. And Watkins Glen is one of the biggest, if not the biggest event on the calendar in terms of spectators. They’ve done a fantastic job at making the track a world class facility. They host events. Throughout the year, they do endurance races there. They do a vintage Grand Prix in the fall, which celebrates the history of Watkins Glen and racing in New York. And if you’re interested in old classic cars, vintage race cars are all there. It’s really a celebration of motor racing and the history of the racetrack there.

Lauren: So Devin, a lot of what we hear today is about the popularity of electric cars, for several reasons. The technology is better. We’re seeing more municipalities, gas stations, and commercial development actually putting in chargers. Environmental reasons. And it’s kind of funny that we go all the way back to this early race on Long Island in 1900, where the only electric car won the race.

Devin: I think it’s also speaks to a couple things. So much of the technology that we know related to automobiles has been developed by racing, whether it’s the engines, whether it’s the aerodynamics, driver safety. Many of these things are spurred on by the racing industry, which is interesting. It’s interesting to know that in 2022, there will be an all-electric car Grand Prix called the E-Grand Prix, which will take place July 16-17th in New York City. Maybe that’s the future of racing. It’s probably the future of cars to begin with. So it makes sense that racing is once again leading the way.

Lauren: And maybe in 100 years, there will be a William G. Pomeroy marker for the first E-Grand Prix.

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.