Devin and Lauren dive into the history of Timbuctoo, an African American settlement founded by philanthropist Gerrit Smith in response to an 1846 law requiring all Black men to own $250 worth of property in order to vote in New York state. To counter this racist policy, Smith decided to give away 120,000 acres of land to 3,000 free, Black New Yorkers, hoping to enable them to move out of cities and work the land to its required value. Lyman Epps and other Black pioneers relocated to the wilderness near Lake Placid, New York — as did abolitionist John Brown, who based his family in North Elba to assist the Black pioneers in their farming.

Marker: Timbuctoo, Lake Placid, Essex County, NY

Guests: Amy Godine, historian and curator of the Dreaming of Timbuctoo exhibit; Paul Miller, director and producer of the upcoming film Searching for Timbuctoo; Dr. Hadley Kruczek-Aaron, director of the Timbuctoo Archeology Project; and Russell Banks, bestselling author of Cloudsplitter.

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with original music from Sean Riley. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

- Blacks in the Adirondacks: A History, Sally E. Svenson (2017)

- “Race and Remembering in the Adirondacks: Accounting for Timbuctoo in the Past and Present,” Hadley Kruczek-Aaron, in The Archeology of Race in the Northeast (2015)

- Practical Dreamer: Gerrit Smith and the Crusade for Social Reform, Norman K. Dann (2009)

- John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, David S. Reynolds (2006)

- Cloudsplitter: A Novel, Russell Banks (1999)

Teaching Resources:

Columbia University: Mapping the African American Past

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute In History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County.

Devin: Today we’ve got a scoop from the Pomeroy Foundation. We’re starting with a marker that will soon be up in Essex County.

Lauren: The marker will be located on Old Military Road in North Elba, just south of the village of Lake Placid. The text reads: “Timbuctoo. Lyman Epps and other Black New Yorkers settled nearby to join 1846 voting rights scheme of justice established by abolitionist Gerrit Smith. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2021.”

So some of us may have heard the word “Timbuctoo” before. But if you’re like myself, it might not have always occurred to you that Timbuctoo was a place in North Elba, in Essex County. So we’re diving a little bit deeper into the history of this sign to find out exactly what was Timbuctoo, where was it, and what was the impact in New York state at the time.

Devin: Yeah, there’s a lot going on with this episode. I think one of the first things we need to talk about, when we talk about Timbuctoo, is to contextualize it within the history of slavery — not only in the country, but in the state of New York. Most people don’t realize, or many people don’t realize, that New York was a slave state. In fact, it was the largest slave-holding state north of the Mason Dixon line. According to the New York Historical Society, during the colonial period, 41% of New York City’s households owned enslaved people, compared to 6% in Philadelphia and 2% in Boston. Only Charleston, South Carolina, rivaled New York in the extent to which slavery penetrated everyday life. And it wasn’t until the Gradual Emancipation Act of 1799 that things began to change.

Lauren: How did the Gradual Emancipation Act work?

Devin: Well, we have to remember it was basically a compromise. New York profited immensely from slavery, so gradual emancipation existed as a series of laws that slowly emancipated enslaved people in New York state without disrupting trade and angering the slave states in the south. It really wasn’t until the law that passed in 1827 that enslaved people actually had a set date in which they were freed.

Lauren: So when that population became free, I think there was fear on the part of the whites that [Black people] would have enough population to vote for anti-slavery legislation [nationwide].

Devin: That’s absolutely true. If we think about the time period — 1840s, 1850s — the slavery issue is percolating nationwide. It’s leading to potential violence, with Bloody Kansas and things like that. So absolutely. This was a real fear among whites, and led to attempts by states, including New York, to disenfranchise free Blacks. I spoke with historian and author Amy Godine to talk about that very point.

Amy: In the exhibition, we make a point of putting the Black experience at the center of the story.

Devin: Amy is also the curator of the Dreaming of Timbuctoo exhibit, which is on permanent display at the John Brown Farm in Essex County.

Amy: It really starts in my view around 1821 or so, when the New York State Assembly enacted a law which deprived Black, free New Yorkers the right to vote — unless they could prove they owned $250 worth of real property. It was racialized voter suppression. This law would effectively disenfranchise Black New Yorkers really until 1870. It wasn’t stripped from the books, and then only by federal law, not by state law. So this law was despised by progressives, by Black New Yorkers, by white abolitionists, and they had tried again and again to get it retracted. And in 1846, at the next constitutional convention for New York, an opportunity arose to address this again — and Gerrit Smith, the radical, abolitionist reformer (who was also incredibly wealthy and land-rich), maybe anticipated that this vote would not go the way he and other reformers hoped.

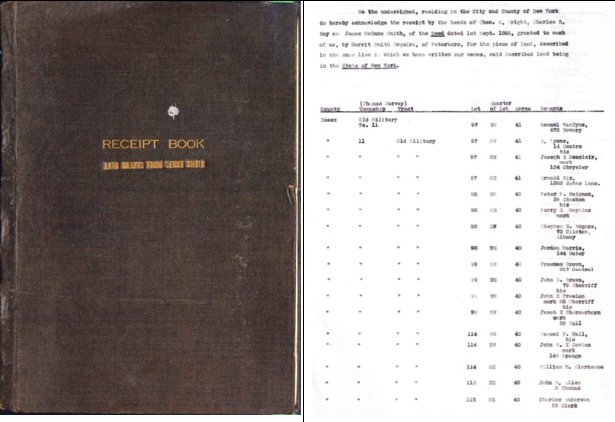

Devin: Gerrit Smith was an interesting character. He’s an abolitionist, he’s a suffragist, he’s a temperance believer, he’s a believer in the “Back to the Land” movement. From his base in central New York and Peterboro, he held land holdings — some estimated it of over a million acres. So he came up with this plan to give 40 acre parcels to 3,000 African American men, [and] raise its value to $250 or more, so that they would be allowed to vote.

Amy: Not that the deeds equaled $250. But if they moved to the land, and improved their lots, they would gain this value soon enough. So it was his hope that, in giving away land he didn’t want, he was tired of owning, he would be striking a blow on so many fronts.

There were white land agents, as well as Black — about 12 men in particular, all of them very active in the anti-slavery scene, most of them active in the Liberty Party, the dedicatedly anti-slavery party. But as it happened, and unsurprisingly, the Black agents he picked were much more active and aggressive about lining up grantees for these gift lots, as he called them. And these were great people, these were really interesting people. This is Henry Highland Garnet of Troy, who was the most militant; James McCune Smith, the great physician in New York City; Theodore Wright, who was an eminent theologian in the city and a leader of thousands, he had a massive church; Jermain Loguen of Syracuse, who was one of the leading pioneers of the Underground Railroad. They had the roots in the communities who could help them line up family after family to sign on for these deeds, which required nothing in the way of action. You weren’t required to move to the Adirondacks if you took one — but it did give you the prospect.

The great preponderance of the grantees who got land from Smith were in New York City. And that’s as he wanted it, he wanted to get Black families out of New York City, which he thought was literally toxic for Black life, where there was simply no hope of getting ahead, getting the vote, and making a living. As it happened, the most grantees who actually came to the region came from Troy, not from New York City. And that was because of Henry Highland Garnet’s incredibly effective organization and mobilization of his own parishioners and other black Trojans. It was also because Troy was closer, and it was simply easier and more affordable to get to the Adirondacks and back out if it didn’t work out.

Lauren: It appeared from Amy’s research that people from the same area tended to settle near each other. So people from New York City that came up, they clumped together. People from the Hudson Valley that came up, they settled together. And then people from Troy that came up, they settled together — and that settlement became known as Timbuctoo. Now it’s unclear where the name Timbuctoo started: some documents from the Black New Yorkers that settled there, it’s called “Timbuctoo,” and also, some of the correspondence from John Brown refer to that settlement as Timbuctoo. So let’s talk about how John Brown came to North Elba.

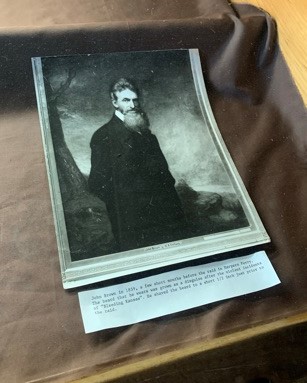

Devin: Yeah, John Brown was an abolitionist, a radical abolitionist, and he was part of the network that surrounded Gerrit Smith. They knew each other, they had corresponded. And [Brown] would become famous for his involvement in Bloody Kansas, and for leading the October 1859 raid on the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry. His goal there was to arm enslaved people and help them rise up against their oppressors — and it totally failed, he was executed for it afterwards. But he’s widely heralded today. He plays a big role in an upcoming documentary by filmmaker Paul Miller called Searching for Timbuctoo. Paul was kind enough to speak with us about Brown’s interest in Timbuctoo.

Paul: There was a moment in history there where John Brown and Frederick Douglass meet, and John Brown, you know, unfolds a map of the Alleghenies and says he has this plan to strike at slavery in the south, and destabilize the institution of slavery. At that point, he’s already consecrated his life to bringing down slavery. And so he has this plan of being able to use the mountain strongholds through the Alleghenies, up through the Adirondacks, and being able to shuttle slaves north to Canada. I believe that when he found out about Gerrit Smith’s, you know, extraordinary land grant giveaway to these Black Americans, he was attracted to that, and saw that as a way to finally enact this plan that he had been thinking of.

He went to Gerrit Smith and said, “If you sell me a parcel of land, I will teach my Black brothers and sisters how to work the land.” Essentially, that’s what he said. He found it so extraordinary that he wanted to be a part of it. And John Brown moved his family there.

You know, the structure of [Searching for Timbuctoo] is kind of two parts. It’s this traditional, historical unfolding — but I also wanted it to illustrate that, you know, history is present. I found the story of this archaeologist up at SUNY Potsdam, and she had been searching for Timbuctoo for a few years before I met her. And she had done a few field expeditions out to find this Black settlement.

Hadley: My name is Hadley Kruczek-Aaron, H-A-D-L-E-Y…

Devin: That archaeologist is Dr. Hadley Kruczek-Aaron, who met with us at John Brown Farm on a blustery, but sunny, day in the mountains.

Hadley: The Browns were here from 1855 to 1863. Obviously, John Brown is executed in 1859. So really, this particular farm was not John’s landscape — it was more his wife, Mary, and the children that were here, who really lived here on a daily basis. But my dissertation was on the Gerrit Smith estate. That work introduced me to the history of Timbuctoo, and I thought to myself, “This is a history that really would be well-served by the archaeology.” We don’t have a lot of written records, especially from the perspective of the grantees who are part of this experiment.

Devin: So when did the project begin in earnest?

Hadley: So the first field season was 2009. That first field season we were on the lot that was originally deeded to Lyman Epps, who is often termed the success story of Timbuctoo. [His family] lived in the region for multiple generations, and that is why I chose his parcel to start this project on, because I thought that that would increase the chances of seeing an archaeological signature.

Lauren: And so what did you see?

Hadley: So what did we see…that story is one of many challenges faced. And so in 2009, we dug on this parcel and found some material culture — mostly from a later time period, probably a hunting camp owned by a local family. There likely was some logging camp trash that we were finding, [we also] found some artifacts that dated to the 19th Century, but not that real concentration of mid-19th Century / second half of the 19th Century material culture that I would have expected, had we hit the Epps homestead. Nor did we find architectural materials that would have been consistent with the house itself. Now, that was very challenging as well, because these were likely log structures, and likely the logs were salvaged. They weren’t digging cellar holes, so in terms of the visibility, I was definitely facing a challenge from the get-go on that. And unfortunately, in 2009, [we] didn’t really find that concentration of material culture that I would have wanted to see.

At the end of that field season, we were having a public outreach day, and picking some people up from the farm here in vans and taking them out to the site, because it’s a remote location and you can’t really take your average car. A student came back and said, “There’s somebody at the farm who’s saying that his family members lived at the Epps lot.” And that was Bobby Chabot, who is the descendant of the Lawrence family. The Lawrences were the caretakers at the farm at the end of the 19th Century until about 1915.

[Bobby] said, “I have a picture of my ancestors’ homestead that was on the Epps lot.” And I got into my car and drove like a maniac from that site, and probably ruined my undercarriage of my vehicle, and got here to talk to Bobby — who has since passed, regrettably. But he shared this history, and shared the picture, ultimately, of this very meager log homestead.

And then, I had been doing some archival research with some turn-of-the-century state maps, and noticed that, on the map from 1900 — that was a DEC map — they had a cluster of houses represented on the map that was just above the property line of what was technically the Epps land. But there was clearly, also, a problem with the survey. And so I said to myself, “Oh my God. It’s not only really hard to find this farm, because I have 40 acres that I have to figure out where this possibly can be. But now, I don’t even know what the 40 acres are that this could potentially be on.” And maybe they were squatting on land that was in close proximity, or maybe they thought that this area was their land, and it actually wasn’t, and it had been re-surveyed. And so we ended up going to where that was represented on the map, which was state land. We dug on that parcel in 2011 and 2013. Again, very hopeful, [but we] ended up only finding that Lawrence family occupation. So that turn-of-the-century / 1900 — they were only there for a few years. They were hit by a forest fire that burned their homestead down.

Devin: Can you just walk through what kind of landscape this would have been during that era, and what these people would have encountered? I think one of the more fascinating things, that I didn’t think of until you were mentioning it, is that the first step would be to pinpoint where their land was. How did they even do that?

Hadley: So there were surveys that were done, surveyors had to be hired locally to mark the land. And you can imagine the undertaking of that. You might think to yourself, “Well, maybe these are small, contiguous lots that are in a downtown core.” Right? Where they’d all be next to each other and really easy to figure out where things were. [But] these are remote lots, heavily wooded lots, on the sides of mountains. And some of them were really hard to access. For the Eppses, for example, it’s about a mile and a half off of the road that would have been here. They would have had to cut their way through, and likely create the road that would have led to their parcel and the set of parcels that were in this one area of North Elba at the time. And so the undertaking of that would have been huge.

And then they would have gone into their parcel, that they would have had to find, and would have had to clear the land to make it a place where you can build your home out of the timbers that you’re taking down, and creating a pasture and farms. The amount of resources that you would have needed to actually get up here and make a go of it would have been substantial. And these were not rich people that would have had those resources.

Devin: And weren’t most, if all of the people recruited from urban areas as well?

Hadley: That’s a great question. My research has tended to focus on Lyman Epps and his experience, and we know that he came from Troy. He was probably in some of the service industries there. He had come to Troy via New York City — I’m not really sure what he was doing there, but again, an urban environment. But he’s born in Connecticut — he’s the son of an African American woman and a Pequot father, actually. My hypothesis would be that he had a more rural existence as a child in his formative years, and that may have had to do with why he might have had more success.

People who look at this history also need to complicate that notion of what success is. Part of success, or part of how people responded to the challenges of this landscape, was to sell their land. Or to, you know, choose not to come up here, and sell it eventually. That was also their strategy for making this work and getting resources out of it if they couldn’t [come up], or if it seemed like the land was not going to be suitable for farming. And so similarly, I think the Eppses used their original farmstead to get footing and to establish their family. And then I think they likely used that land for timber resources, according to the tax records. So they were still using it as a resource, but then moving to this other parcel — that’s part of their strategy and creativity for making this work.

Lauren: I think that dovetails into why you applied to the Pomeroy Foundation for the historic marker. So could you tell us about that?

Hadley: Yes. So it’s always been a goal of making it more a part of public memory. People still don’t know about this history and are surprised to hear about it. And so one of the great tools that we can use is to get a historic marker to make the commemorative landscape more inclusive.

Lauren: Only a small number actually settled on the property and far fewer stayed long enough to see the land improved to reach the $250 worth that they needed for the right to vote. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the project as a whole was a failure.

Devin: If we think about these characters as well, the definition of success as you note, Lauren, is complex in and amongst themselves. The Epps family was able to make a go of it. For John Brown, was Timbuctoo a success? Well, we know the story of John Brown. We know the story of Bloody Kansas and his move from a radical, but nonviolent, abolition, to a violent, radical abolition, which took place as he was living in North Elba. John Brown’s original plan, the one that he definitely told to Gerrit Smith, was to use the mountain ranges as this conduit where he could conduct raids and free slaves, and then take them north through these mountain ranges. And that was his original plan — I don’t think he necessarily said anything about attacking the U.S. armory at Harpers Ferry. It’s unclear where that idea came from.

Lauren: John Brown asked some of the people in the Timbuctoo settlement to join him, to join his army, to come be a part of Bloody Kansas or the Harpers Ferry raid. And they say no.

Devin: They wouldn’t.

Lauren: They all say no.

Devin: Including Lyman Epps.

Lauren: Yeah.

Devin: Later for Harpers Ferry, some African Americans do join him — not necessarily from Timbuctoo. But it’s telling that before the raid, he approached Frederick Douglass for his support. And Frederick Douglass turned him down because he knew it would fail, and he didn’t believe that that was the best use of resources.

But on the other hand, [Brown’s] activities at Harpers Ferry, specifically, many historians look at as being a catalyst, or one of the first volleys, of what would become the Civil War — which, in the end, did lead to the emancipation of the enslaved in our country. So John Brown was executed in 1859, he never lived to see that, but he may well have known that his actions were part of a larger story that was playing itself out during that time.

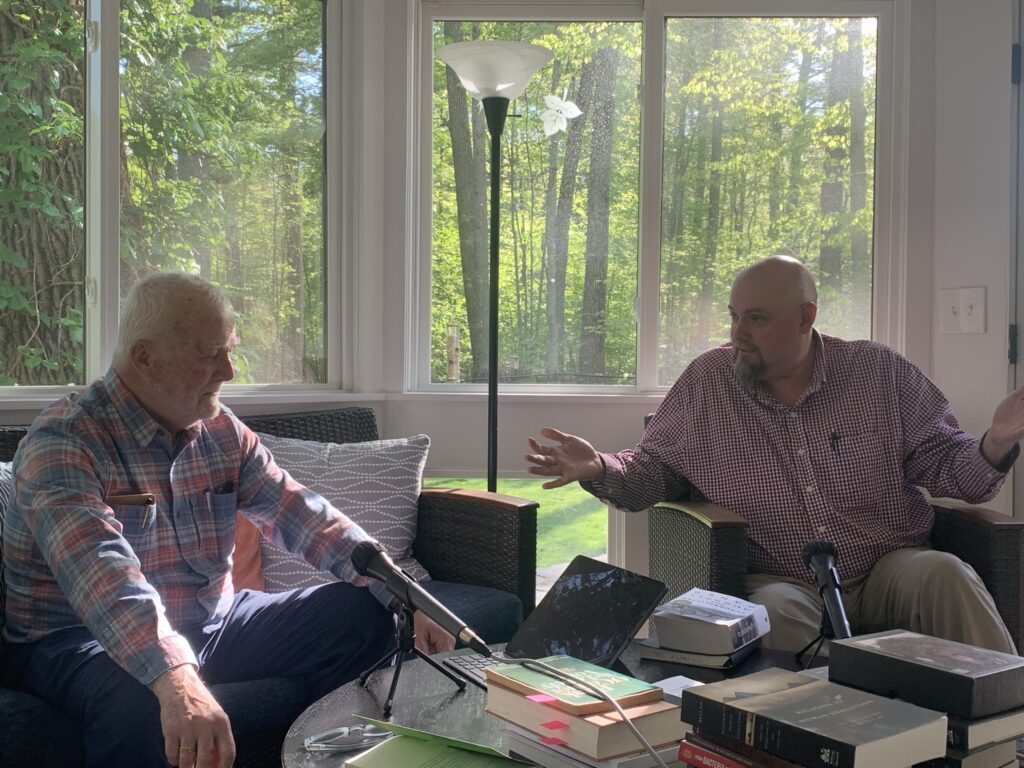

I had the opportunity to sit down with one of my favorite authors, Russell Banks, who wrote the novel Cloudsplitter, which is about John Brown and his family.

Devin: So let’s talk about the genesis of this book, Cloudsplitter, which is just an amazing story based in in some historical fact, but there’s also some artistic license taken. What drew you to this story and specifically with Timbuctoo, and also, of course, John Brown?

Russell: Well, you know, it’s really, purely by accident. Brown was a figure in my imagination, already a fairly vivid figure, going back to my university days in the ’60s, in Chapel Hill — the University of North Carolina, where I was politically active, as was most anyone who was in college at that period was. Brown was someone who was invoked by most anybody on the left: anti-war activists, civil rights activists. You were as likely to see a poster of John Brown on a dormitory room wall as a poster of Bob Dylan or Jimi Hendrix, so he was a heroic figure and romanticized.

And then in ’87, my wife and I moved to Keene, New York, upstate. And I realized fairly quickly that, you know, his body lies moldering down the road, just some little ways in North Elba. I was sort of astonished to find that out, because I hadn’t known it. And then I began poking around, doing a little research. And about that time, I could see his sort of re-entering not just my personal imagination, but the national imagination.

The narrative of American history where Brown is placed is really interesting and at a crossroads. It sits where white American history is in a permanent (it would seem at times) argument with African American history. But nobody disagrees on the facts. The facts of John Brown’s life and death were known in 1859, when he died, when he was executed. It’s the meaning of those facts, which was so interesting and important, and the fact that, to African Americans, by and large, like James Baldwin, or WEB Dubois, and so forth, Brown was a heroic figure. But to most white Americans, he was a madman.

But the legacy of it is, if it can be told enough times, and and with enough clarity — and not just sentimentalize, and say “isn’t it amusing and interesting and kind of touching that there was this small colony of the saved,” as it were, sitting there in North Elba, in the middle of the Adirondacks. If this story can avoid that sentimentalization, and can point toward this early attempt to provide racial justice and reconciliation through cooperative work — by both white and Black men and women, then, I think that’s its best emblematic use, really.

Amy: What we know about Timbuctoo — and it’s the only name we tend to associate with this, really — is because of John Brown’s interest in it. His death, his burial, and then the subsequent pilgrimages over the next 100 years, all serve to sort of glorify this site and make it a place of white sacrifice. The efforts of the Black pioneers are completely sidelined by this, but there were longer-settled and longer-lasting settlements in St. Armand and Vermontville. Some descendants of those early communities were in the Adirondacks as late as 2010.

Paul: I think about myself, and my family — we’re looking at property in the Adirondacks. We’d like to move up there, and settle up there. And so what impact does that have for an African American man today? To know that, yes, there were these Black settlers there before the Civil War, and there were people who fought and sacrificed to further diversify the area, but also fight for equal rights and human rights.

In some ways, it can be demoralizing to think that we’re still fighting the same things that we were fighting more than 150 years ago. But also 150 years ago, there were white Americans and Black Americans working together to solve these problems, and battle them together. That is hopeful at a time when it can be easy to feel hopeless.

Devin: Thanks for joining us for A New York Minute In History, a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County.

Devin: We have a lot of people to thank for this episode. Paul Miller: his documentary on Timbuctoo is currently in production. Historian Amy Godine: her book, Black Woods, is set to be published by Cornell University Press. Hadley Kruczek-Aaron from SUNY Potsdam, and novelist Russell Banks. Our producer is Jesse King.

Lauren: For more information on Timbuctoo and any of these projects, go to wamcpodcasts.org. We’ll see you next time on A New York Minute In History.