May is Asian American and Pacific Islanders Heritage Month and in celebration this episode highlights the community history of Manhattan’s Chinatown, one of the oldest and largest Chinese and Chinese American communities in the United States. The episode tells the story of how during a time of change in the late 1970s the Chinatown community moved to preserve and archive its own history, which had long been ignored and marginalized by the dominant cultural institutions of the area.

Featured image: Chinatown, Manhattan. Image: NYC Tourism.com

Marker of Focus: Chinatown and Little Italy Historic District, Manhattan.

Guests: Dr. John Kuo Wei (Jack) Tchen, Director, Clement A. Price Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience at Rutgers University Newark and Ashley Hopkins- Benton, Senior Historian and Curator at the New York State Museum.

A New York Minute in History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio and the New York State Museum, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading and Resources:

New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882 by John Kuo Wei Tchen (2001).

Back to the Basics: Who Is Researching and Interpreting for Whom? by John Kuo Wei Tchen, The Journal of American History (1994).

New York Chinatown History Project by John Kuo Wei Tchen (1987).

Teaching Resources:

Museum of Chinese in America: Learn

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library: Chinese American Exclusion/Inclusion

Library of Congress: Asian American and Pacific Islanders Heritage Month Resources for Teachers

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York State historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. In honor of the upcoming Asian American [and] Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we’re going to be talking about a marker located at 151 Mulberry Street in New York City, which is in the borough of Manhattan, and the text reads, Chinatown and Little Italy Historic District has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010, by the United States Department of the Interior, William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2022.

Now, this marker is not one of the traditional blue and gold markers that we usually talk about. And in this case, if you have a structure that’s been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, you can apply to the Pomeroy Foundation. Because when a structure is nominated for the National Register, there is no form of signage that you are given as part of being listed. So this offers a chance to have signage, which alerts the public to the fact that this is an important historic structure. In this case, the plaque itself is on the side of the building; because it’s in New York City, it would be really difficult because of the congested sidewalks to have a marker on a traditional pole, like we see in a lot of other places. So in New York City, it’s much more common to see plaques on the side of the building. And actually, the building that it’s on is the Italian American Museum. As mentioned, it is the Chinatown and Little Italy Historic District. And we’ll talk a little bit later about why those two communities are in the same location.

The marker itself was applied for by the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council that was founded in 1955. The neighborhood is bordered by the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges and the East River. And at that time period in the 50s. Tensions were high, there was gang violence, and this area was becoming one of the city’s first racially integrated neighborhoods. And so the neighborhood council was created to try to resolve some of the conflicts and to serve as a channel for communication among settlement houses, churches and community leaders. And this information is according to their website.

So let’s go back and talk about Chinatown – which is going to be our focus this month – and talk a little bit about the origins of Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Devin: Manhattan’s Chinatown is one of the oldest in the country. It’s one of nine in the city right now. It was the oldest and the largest for many years. It’s located in lower Manhattan and you mentioned Little Italy, which abuts Chinatown on the northern side.

Stereo-Travel Co. Doyer Street, Chinatown, N.Y.C. New York Chinatown, 1909. Courtesy Library of Congress.

When we think about Chinese immigration history in the United States, the first wave of immigrants really happens around the Gold Rush on the West Coast. And it was not until kind of after that point in the 1850s, it’s estimated that the first Chinese immigrants began coming to New York City. And the reason that they came was the reason that New York City became such an immigrant hub: it was because of the port, right? And so because of this port culture, not only did Chinatown exist and more and more Chinese immigrants began to settle in the lower part of Manhattan; also, the Lower East Side, as I mentioned, became an ethnic neighborhood for Jewish immigrants and other immigrants from Eastern Europe. And then of course, Little Italy. All of these people were associated, at least early on, with the Port of New York City. Many of them either worked on the port or had businesses that served people who did work in the ports. When we think of Chinatown, many of the early settlers there, opened businesses such as laundries, restaurants, stores that often served the port community.

In the 1850s and 1860s, as more Chinese began settling, there became a kind of racist backlash against the settlers, many of whom were working class. So there began to be conflict between working-class white Americans and these Chinese immigrants and other immigrants. But specifically, there was bigotry directed at Chinese immigrants, because they were seen as representing many of the concepts that were false concepts, but that Americans believed when they thought about “The Orient,” or Asia that, that these cultures were a decadent culture, that they were not Christian. They had different religions, different customs, they dressed differently. So there was a kind of an easy way to think about othering Chinese immigrants. And this led in many ways to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which specifically put quotas essentially slamming the door on Chinese labor coming to this nation at all.

To get more context on the origins of Chinatown, and on the Chinese Exclusion Act, and its effect on immigration, as well as the community that already existed in New York City. We spoke with Dr. Jack Tchen.

Dr. Jack Tchen: Hello, my name is Jack Tchen. My full published name is John Kuo Wei Tchen. My work has really been about building capacity in communities that have especially been disenfranchised from really historical records. And as historians, we know that what’s written down and what is kept in libraries and archives are what are oftentimes the stuff that history books are written from. I worked on a – well it’s now a book – called New York Before Chinatown. And it’s really about the role of Orientalism in the shaping of American culture, from 1776 to 1882, which is when the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. Most Americans don’t know the Chinese were excluded from this country. Technically, that was repealed in 1943, when the US and China became allies in the fight against Japan. It wasn’t effectively repealed until 1965 and 68. Because in ‘43, the laws defaulted to the 1924 Immigration Act, which is really an act as defined by the eugenics movement. The eugenics movement is a part of the history that I’ve also worked on; [its] something that we don’t understand, and it’s ongoing legacy and the impact on not just the kind of attitude that was dominant in scientific racism against African Americans, against indigenous people and really segregating them from the culture. But of course, it got applied towards Chinese in 1882. And then that emboldened hardcore eugenicists, thinking that they would then enact an immigration law that would exclude the great majority of so-called “inferior” European immigrants as well. So the ‘24 quota for Chinese, 105 people were allowed a year. And so from, technically the repeal of the exclusion law, that got it, the immigration policy was defaulted to the eugenics laws. So those were not changed until ‘65 and ‘68. I go into detail because these historical forces have tremendous influences on not just whether Chinese or Asian Americans were acknowledged, but also the history collections themselves and the history profession themselves and what’s collected, what’s ignored. And if Chinese are excluded from this country, they’re not thought to be worthy of citizenship or could be citizens, and therefore, women were excluded and families were really very marginalized. So it really explains why there’s such a gap. It’s an intellectual kind of black hole, where these were people who just didn’t quite count and therefore they were not part of the collections.

Devin: Early historians of Chinatown such as Jack Tchen quickly realized that the community itself was marginalized within the historic record. And they realized that institutions had not been collecting material related to the history of Chinatown. The archives did not have a historical record of the people that lived there, in many ways because of the language barrier, but also because of the priorities of the collecting institutions. So when Jack Tchen and others began studying and looking at Chinatown as having its own history, they realized that this archival record did not exist. So they created the Chinatown History Project, which was one of the first community history projects in which public historians went into the community itself, and literally knocked on doors and went door to door asking for people to share their personal histories because they began the project by focusing on the laundries in Chinatown, which had not been looked at historically or studied, but were so numerous and important not only to that community, but to New York City as a whole. So, you know, it really was a groundbreaking project that has led to other similar type projects in other communities around the nation.

Dr. Jack Tchen: In terms of my own background of being a Chinese immigrant, really a Chinese refugee; As I began looking for those records, they were not to be found. At the New York Historical Society, really little bits and pieces. At the New York Public Library, bits and pieces. Oftentimes what would show would be advertising trade cards or racist caricatures in Frank Leslie’s or Harper’s Magazine. So it really drove a curiosity and a need to begin building archives and collections personally, but then also, as we started the New York Chinatown History Project, to begin building up those archives. So I started out really, as someone doing community-based history. So, my start really was as a public historian as someone also collecting materials and I got a PhD at NYU, in American history, but also: in thinking through questions of public history and a dialogue approach towards history, which is really acknowledging those who have been left out of history and how to include their records and their voices and their experiences.

I should say that I’m not from New York, nor near Chinatown. Originally, I’m from the Midwest. And I arrived in New York in 1975 and began volunteering at a community arts and cultural organization called Basement Workshop. And one of the first people I met was Fay Chiang, someone who hasn’t received her full due in terms of the heroic roles that she played just in building the Basement Workshop and writing grants and doing the kind of unsung work that oftentimes women do. But in particular, she was also this fantastically talented poet, and visual artist. So it turns out that besides those qualities about her, she was also the daughter of a laundry family. I began really thinking deeply about: what does it mean to have been part of the thousands of laundry families that really built up New York’s Chinatown? So I had the eyes of an outsider, but also working with people from the community itself. So, I began kind of digging deeper and deeper and looking at books, reading, studying, and realized that that history had not been really documented from the community’s point of view. So that became the basis of our, of our work. I was able to work with some other folks who are just kind of freshly minted from college, to form the New York Chinatown History Project and to write a proposal that actually got a significant size grant for people who are willing to work for very little creating a new organization, going into dumpsters.

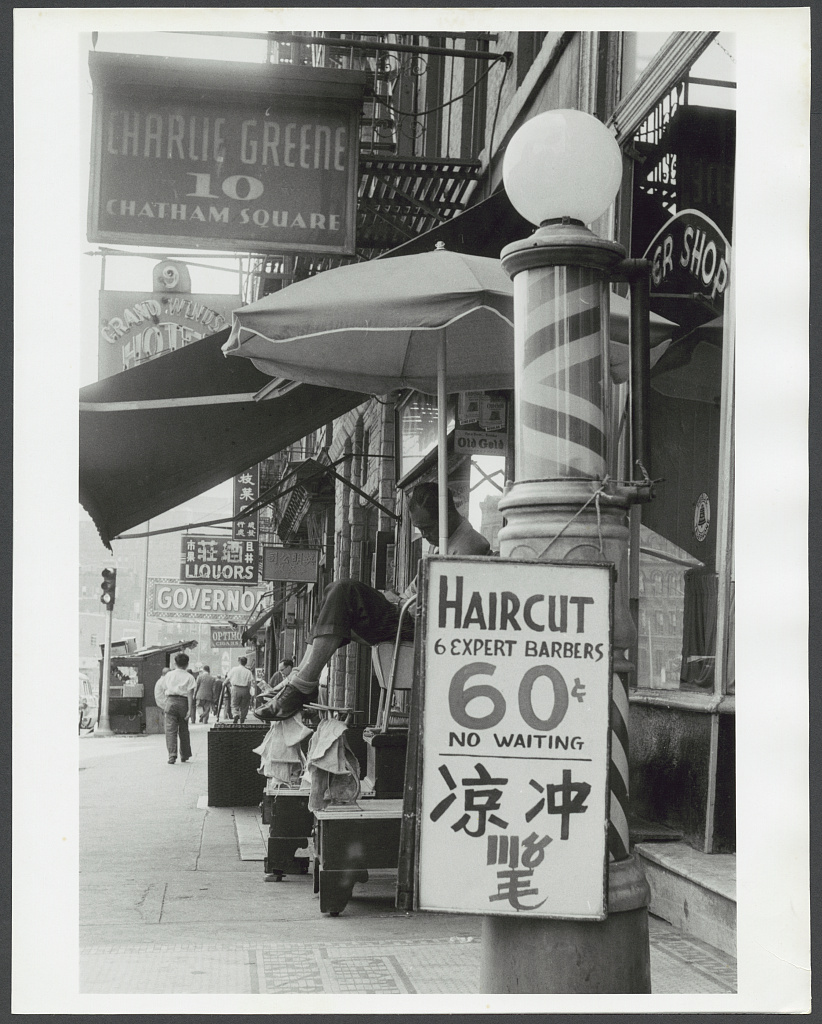

Rizzuto, Angelo, photographer. Businesses along Chatham Square, Chinatown. United States New York Chinatown New York State, 1956. Courtesy Library of Congress.

And at the time, our office was on East Broadway, which was kind of a transitional neighborhood area. And it’s just at Chatham Square, one of those historic squares that has largely been forgotten by people today. The Bowery goes up from there, the early history of New York is very much the Bowery where working class folks were living, but also a very intermingled community of African Americans, early Chinese. So what was happening at Chatham Square was that the leases for many of these stores were coming up and the leases had 99 year leases. So this was a material culture history that was not registering for the New York Historical Society or the Museum of the City of New York. Quite frankly, it was only the local folks who cared about these places, because they had been, of course, part of the everyday life. And even then, [ ] Pharmacy, which is the oldest pharmacy in the city, at the time, was just being tossed out; all their storefronts, all the stuff inside. So what I realized is that, well, Chinatown was never strictly Chinatown, it was always part of the port culture. And the stores that were closing down, were emblematic of that mixture of what was going on. So from the very beginning, we never represented Chinatown as an isolated, segregated community that only cared about itself. It was always intermingled with Irish, with African Americans, with – I heard lots of stories about the Jewish community coming in, having meals. We weren’t intending to collect lots of stuff. But as the stores start closing down, I just could not bear the thought of these things being thrown out. Certainly [to the] uptown historical societies, this is too lowly, really, quite frankly, for them to collect. We did strike an early relationship with the [New York] State Museum, which I think at the time really was one of the few places that really valued the items that were in some of these stores. So we opened at the at the New York State Museum. And we also opened at the New York Public Library on 42nd Street before they had a gallery. We were really one of the early shows that happened in their entry lobby area. So we got some great coverage from the New York Times. And in that way, I think the New York Times coverage, ironically, also got the Chinatown community to take this group of young people that not all of whom were from the community itself, right? We started being taken more seriously. Because we were able to document the history of Chinese laundry workers, which is not the history of Chinatown, per se, but of those ten thousand or so laundry workers who were in the metro region. And it’s really the laundry workers who were the early financial base for Chinatown itself.

Devin: Because there was no repository for this material, there was nowhere for them to possibly donate it, whether it be to a museum or to another institution. So the New York State Museum agreed to take material from three general goods stores, and combine them into one exhibit that would focus on the Tuck High store, which was at the time 101 years old, was closing, the family was moving away from the business, and the museum decided to interpret Tuck High as it would look in the 1930s using a collection of material from three different stores. We spoke with curator Ashley Hopkins Benton about the Tuck High exhibit.

Ashley Hopkins Benton: My name is Ashley Hopkins Benton. I’m a senior historian and curator at the New York State Museum. I focus on social history, especially women’s history, immigration, LGBTQ plus history. And I’m also interested in our toys, glass and ceramics collections.

The Tuck High store was founded in 1879 by a Chinese immigrant Feng Wen Lee. And it was kind of a general dry goods store. They had a number of different products through their history. They carried herbs and some food items and supplies like walks and cooking tools, and some ceramics. But it was also very much a community center in Chinatown. It was a place that men that also worked in Chinatown would go to socialize, to get a meal. They had a pocket that served kind of as a post office, so for men that were working in Chinatown and trying to communicate with their relatives in China, but maybe didn’t have a permanent address, they would receive mail there. They also provided services where they would write letters for people that were not literate.

And so it was located originally at 19 Mott Street and it was there for 50 years. And then in 1929 It moved to 24 Mott Street, which is the location that the museum ultimately collected.

By 1980, Chinatown was changing. There was gentrification, the rents were going up astronomically. And the Lee family – at that point it was Wah On Lee and Coon On Lee – decided that they couldn’t keep the business anymore and they were interested in selling it. And thankfully there were people that were really interested in Chinatown’s history that were able to make the connection with the New York State Museum. And so the museum went down and met with the Lees and observed their business and ultimately decided to purchase large parts of the store: the fixtures and some of the merchandise, and the equipment, the cash register, the cooking equipment, and then other parts were gifted by the Lee family. And while they were in the process of making that collection, and working with them, they found out that there were two other stores that had recently closed, so they also acquired the contents of Sun Goon Shing and Quong Yee Wo. And the exhibit that you see today in the museum is a reconstruction of the front room of the Tuck High store filled with the materials from those three stores.

Devin: Maybe you know this, or maybe not, what does Tuck High mean?

Ashley: It means “high integrity.”

Devin: You know, we deal in the museum world with material culture. And so what does that tell us about both the store but also the community?

Ashley: Well, I think it tells us some of the ways that they were supporting the Chinese community, ways that they could harken back to their Chinese heritage and really retain those customs. So there is a large collection from one of the stores of calligraphy paper and calligraphy supplies and writing elements. So that’s one big theme. Um, there’s also a very large collection of herbs and medicines that would be used in traditional Chinese medicine. And the store also employed a druggist or – he was actually referred to as the drug man – who worked in the back and would talk to you about your ailments and help prescribe various things that would help you feel better.

The stores that we know about, you know Tuck High closed in 1980, Quang Yee Wo, closed earlier that year. And then Sun Goon Shing actually closed around 1972. So – and was warehoused. So I think there were so many of these stories happening all at once that it was a wake-up call. There’s some really great photos that the curators took, like as the shop was closing. So, because of the rising rent, there was a hard fast deadline of: this is the day the Lees need to be out. But they also were interested in operating the business up until the last day. So the curators were literally there like taking pieces of the building out while the Lee family was still selling materials propped up on boxes with a board and selling to the regulars.

Chinatown is right now undergoing another wave of gentrification and rising rents. So there are a number of stores and restaurants that have been around for generations that have closed in the last couple of years. And that’s caused a lot of change, again in Chinatown, but there are still family businesses that harken back to some of these traditions and do serve as a community stopping place. And it’s a place where you can get a variety of goods. And what’s really interesting as an observer who’s up here in Albany rather than down in Chinatown very much is that a lot of them have an amazing social media presence and are sharing their stories and how they’re serving the community and the ways that they’re trying to preserve their own history as well through social media. So that’s really fun. So K.K. Discount is one, which is a really kind of general store that sells supplies for a variety of things. But they’ve also worked to kind of keep the community together and to share about the good things that are happening in Chinatown. And then another example that I was thinking about is Wing on Wo [&Co.], which was actually located just next door to where Tuck High ultimately was located and is now the oldest continuously operating store in Chinatown. And through their W.O.W. Project, they’re promoting the Chinatown community and keeping it vibrant and the businesses vibrant.

When Tuck High came to the museum, there was really a great amount of communication between the museum staff and various people in Chinatown. So not only the Lee family, but the families associated with the other stores and people that were working on Chinatown history. And there is a great trove in our collection of all of the reports that were in Chinese language newspapers when it opened in 1981 in the museum. So that was a great excitement. And as I said, continued communication between Albany and Chinatown. There was also a lot of excitement, just in the reports that the museum was collecting the space before it was even open. There was a New York Times article and there were numerous letters from people all over the country, some of whom, as I said, visited Tuck High with their families when they were younger, and we’re just writing to say “I’m so glad you’re preserving this history. This is my family memories.” But one of those was actually from a gentleman in Albany who had traveled with his family regularly to visit the store. He was writing because he was excited that we were saving it. But he had also read that there was interest in including mannequins in the space, which was an exhibit technique that the museum regularly did, to people our spaces and kind of show the way that people interacted with them. Those mannequins that are in the museum are cast from real people. And he offered himself up as the model for the cast that would be made for Tuck High. So the druggist that you see is actually a man that lived in Albany, who had been to Tuck High in his younger years.

Lauren: It’s fascinating to me as a public historian, and probably you as well, Devin, that the work Dr. Tchen was doing in the 1970s, and 80s, is so far ahead of his time, it seems like as we’re talking about it, this is a project that could be going on currently. And when you look at the field of public history, one of the things that we’d like to focus on is helping communities tell their own stories. And it takes a lot of effort to do that, you need to gain trust, you need to build relationships with the people in those communities. And if you want any hope of being able to fill those holes that are in our archives, this work needs to be done now before these communities disappear.

Devin: I think that’s absolutely true. And I think part of the process is not only building the relationships, but sometimes it’s getting the communities themselves to understand the importance of their own history. Dr. Tchen told us, it was a struggle at times for the Chinatown History Project to get some of the residents of Chinatown to, to understand the value of their own history. And, and that’s often the case, as we see in communities that we work with across New York State.

Lauren: I know that sometimes when I go into an oral history with someone I want to speak with about a particular event in the past, some people tend to think that their experiences are not important or even worthy of an oral history, you know, and so I think one of our jobs is to help people realize that their stories are worthy of being told and collected. And to make them realize everyone’s story is a piece of the larger cultural fabric, and that all of those representations need to be included for us to have a larger picture of where we are today. So even when communities think that their story is just a tiny sliver of the overall pie. It’s the job of the public historian to help them realize that their stories should be collected, and they do have meaning.

Dr. Tchen: As the Chinatown History Project began to develop, and we became a museum, I really began thinking about these questions in a larger way about the idea of a dialogue-driven museum as opposed to a collections driven museum or an academically-defined Museum, right? How can we begin to formulate what’s important and how people understand things from their point of view, and to really privilege the community language. It’s really from that kind of lived and embodied experience that these values really became important to me. You know, our first name for the New York Chinatown History project was the Center for Community Studies. And I really do believe that place matters, communities matter, and that ultimately, it’s through public history more than academic history, that people get a sense of place, community meaning, community building and being able to locate themselves in these stories.