On this episode, Devin and Lauren discuss a William G. Pomeroy marker recognizing the contributions of the Mossell family in western New York, and their efforts to successfully integrate the Niagara County city of Lockport’s public schools in the late 19th century — nearly 80 years before legal segregation ended nationwide.

Marker of Focus: Aaron Mossell, Lockport, Niagara County

Guests: Melissa Dunlap, executive director of the Niagara County History Center, and Heidi Ziemer, outreach and digital equity coordinator for the Western New York Library Resources Council

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with help from intern Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Diane Ravitch, The Great Schools Wars: A History of the New York City Public Schools

David G Garcia, Strategies of Segregation: Race, Residence and the Struggle for Educational Equality

Laverne Bell-Tolliver, The First Twenty-Five: An Oral History of the Desegregation of Little Rock’s Public Junior High Schools

Michelle A. Purdy, Transforming the Elite: Black Students and the Desegregation of Private Schools

Teaching Resources:

New York Historical Society: Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow

New York State Museum: Educator’s Guide to Dr. King’s 1962 Speech

PBS Learning Media: Civil Rights from Orlando to New York

New York State Archives, Consider the Source New York: Civil Rights: The Hillburn Petition

Continuing Teacher and Leader Education (CTLE) Credit: The New York State Museum is an approved provider of Continuing Teacher and Leader Education (CTLE). Educators can earn CTLE credit (.5 hours) by listening to this episode and completing this survey. Please allow up to two weeks to receive confirmation of completion.

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York State historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. We’re celebrating Black History Month by focusing on a little-known story coming to us from Western New York. This blue and yellow historical marker is located in the city of Lockport, in Niagara County, and it’s placed along the Erie Canal within the Josephine Carveth Packet Park. The title of the marker is “Aaron Mossell,” and the text reads: “Aaron Mossell and his son Charles were local residents who advanced the struggle to integrate Lockport schools open to all regardless of race by 1876, William G Pomeroy Foundation, 2018.”

Now, the location of the marker is not directly related to Aaron Mossell or his family. But the site was chosen because of the visibility it offers. The marker’s on the site of a public park in an area that gets a lot of foot traffic, and therefore reaches a wider audience due to this placement. Hopefully, people visiting the park will see the marker and want to learn more about Aaron Mossell and wonder why they haven’t heard that name before. So Devin, who was Aaron Mossell, and maybe before we get there, how do we pronounce the name?

Devin: Well, that’s a great question. And I think our two guests, Heidi and Melissa, have told us that in Lockport it’s actually pronounced as mo-ZELL, while the family pronounces it MOSS-uhl. So we’ve chosen to go by the family, and call the family the Mossell family.

Lauren: And this isn’t uncommon, right? I mean, we know lots of times when there are family names that are pronounced different ways depending on where you’re from. So, we’re choosing to pronounce the name Mossell as the family does.

Melissa: I’m Melissa Dunlap and I have been with the Niagara County Historical Society almost a full 33 years; 29 of them as the executive director.

Heidi: My name is Heidi Ziemer. I am the Outreach and Digital Equity Coordinator for the Western New York Library Resources Council. In my job, I work with our libraries and archives with their special collections, and one of the things I tried to do is connect educators with primary source materials from these collections. And I had a group of teachers I was working with the year that I went to Melissa and was asking for information I think I started out asking for information about the Erie Canal — and she mentioned about the Mossell family, and I became hooked.

Melissa: Aaron Mossell, he built the commercial hotel in Lockport and we actually have the arch that went over the doorway that has his name.

Devin: And Nathan was Aaron Sr. and Eliza’s son?

Melissa: Yes, one of them.

Devin: And they also had Aaron Jr. and Charles.

Heidi: There are articles about Aaron Jr’s early law career, and the fact that he was defending people very successfully. And their sister Mary, married a professor from New Jersey, I think?

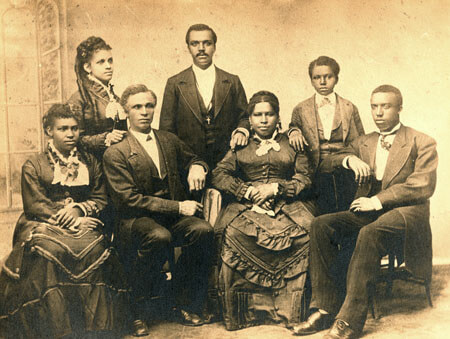

Melissa: And then the granddaughter – Aaron’s daughter, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander – she was the first woman in the country to get a PhD in economics. And then you go down to the great grandchildren, Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, she was vice president of Manhattan College. Her first cousin, he was the head of Cardiology at Yale Medical School.

Devin: What a… Has anyone ever written a book about this family?

Melissa: I would hope somebody would!

Heidi: We have actually been trying to figure out a way that we could get a project.

Melissa: A cousin of Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter is Ossawa [Tanner]

Heidi: The artist.

Melissa: And he actually wasn’t an expatriate. He went to France to live because he was not happy with how Blacks were being treated in our country. One of his works of art was the first art from a black artist that was installed in the White House during the Clinton Administration.

Devin: Aaron Mossell Sr. was the scion of a very prominent African American family. But they didn’t start that way. He was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in the mid 19th century, during a time when the vast majority of African Americans were enslaved. But he wasn’t. And why was that? Well, it was because his grandfather, who was enslaved, purchased his own freedom and the freedom of the rest of his family from his enslavers. So, he was a free black living in Baltimore. He was a brickmaker. So, that’s who he was. He married Eliza, and they moved their early family – they had their first two children in Baltimore – and they moved their family to Canada. And why was that? Well, because of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which caused a lot of consternation among free Blacks everywhere, but certainly in a place like Baltimore that was part of the South. Enslavers were going to come and take them into bondage, whether they were free or not.

Lauren: One of the other reasons that the Mossell family moved to Canada was that Aaron Mossell placed a heavy importance on education for his children, and he felt that the education provided to them in Canada would be much better than what was available in Baltimore at the time.

Devin: So he moved his family – This is the mid 19th century, around the time of the Civil War – and his family lived there for a period of time, and we’re not really sure what happened, but there was some sort of situation with a land deal that went wrong.

Heidi: Entailment, I think it was? Entailment laws, yes. The British entitlement laws. A woman claimed back the property that Aaron had been living on.

Melissa: She certainly gained, because it was an unimproved property when he bought it, and he built the structures: the house, the barn, and then all of the contents also became hers, any contents in the house.

Devin: Unfortunately, the Mossell family was forced to give that up, and they ended up moving to Lockport.

Melissa: The only thing he had was a horse that he had sent to the Blacksmith to be shoed. He sold the horse and that’s how they wound up in Lockport, New York. From there, he was able to buy a brickyard that belonged to Mr. Trowbridge. And he eventually worked up to almost fifty workers, and had a really prominent business. But he also was an extremely well-educated, thought-out person and he was an activist. The two AME churches that were in Lockport had split, and he made the concerted effort to get them to compromise and join as one congregation again. He also was a philanthropist because he donated bricks, Southern Hamilton, Ontario. He donated the bricks when the AME Church was rebuilt in Lockport. But we’re not sure if he donated the bricks for the High Street School or if he gave them a really good discount. But he had those bricks.

Heidi: One of the things that we find in searching New York State Historic Newspapers is that Aaron senior served as a juror in the municipal court system. He participated in the county fairs and won some recognition for his cornice work. You know, they were a part of life; he was very respected. The family was very much respected in the community.

Devin: So we know obviously, there’s an African American community in Lockport that they were able to tap into. Do you know, generally, how large that population would have been in the 1870s? Was it a very large part of Lockport or are we talking very small?

Melissa: It was small, I mean, currently, it’s 9 percent of the population. And I think at that time, it was probably between… probably about 12-14 percent.

Devin: Okay.

Melissa: But because Lockport was a Quaker community, during the Fugitive Slave law, twice they tried to capture freedmen in Lockport. And Lyman Spalding, who was a prominent businessman, he got the canal workers to come and rescue the man that they were trying to take. And that happened on two occasions in Lockport. So the community was very supportive.

Devin: We mentioned that Aaron Mossell and Eliza were very interested in educating their children, and we’ll talk more about that later. But one of the things they quickly came up against was the fact that the Lockport schools were segregated, meaning there was a school for white children and there was a school for black children. Now, I think it’s important for us to realize here in New York State, that school segregation was not just a southern phenomenon, nor was it something that suddenly went away. It’s like slavery itself in New York. Many New Yorkers don’t realize that colonial New York – from 1626, throughout the American Revolution, until the formation of the state and up to 1827 – was a slave state. Not only a slave state, but the largest slave state north of the Mason-Dixon Line. So, I think school segregation and desegregation is something that many New Yorkers don’t realize is a New York story and a northeastern story.

In the case of the Mossell family in Lockport, Aaron and Eliza quickly realized that not only were the schools segregated, but the black school had less resources given to it. The teachers sometimes were not the better teachers, they were maybe new teachers, the resources for equipment and supplies and the buildings themselves were not the same standard that white students were given.

Heidi: In New York State 1873, The New York State Civil Rights Act of 1875, you had the Federal Civil Rights Act passed. And I think those two were the catalysts for people recognizing the opportunity to try to integrate the schools. Because it was around that time when Aaron Sr. and his son Charles both made the effort to have the Lockport schools integrated by closing the black school.

Melissa: Actually, they started in 1871.

Heidi: Right.

Melissa: The first time, they petitioned.

Heidi: Right.

Melissa: and December of 1872, the colored school was supposed to be discontinued at the close of the term. Then on December 30, they rescinded that, and decided no that wasn’t going to be, so they started a boycott.

Heidi: In the Lockport Daily Journal in January of 1873, Aaron Mossell writes to the editors, and he says “SIRS: The colored people of the city had their hearts gladdened by reading in the papers, a short time since, that their children were about to be admitted in the District and Union schools of this city. But their joy was soon turned into sorrow, for your issue of the 30th of December contained information that the Board of Education, which had passed a resolution to discontinue the colored school and throw open the common schools to the colored children, had on 27th of December rescinded the resolution.” And then he goes on to say that a meeting was held at the South St. Zion Church. And it was organized by electing Aaron Mossell president and James Nichols secretary. So they organized, and then they resolved – they have a resolution in there – that they’re basically going to boycott. The children will not go to that school, but that they will go to the respective white schools. And that if they were not going to be admitted, he does say, “That if our children are then refused admission to such schools, that in view of the fact that the colored people pay part of the taxes supporting the said district schools, that then in case of such refusal, such steps be taken at law as will secure to the colored people their rights in the premises.” So they’re threatening legal action, if the boycott is not successful.

Devin: You know, this economic starving by boycotting the schools, that’s actually a fascinating mode of civil disobedience. You know, instead of protesting and marching with signs, just stop sending your kids and it will become an economic burden to the point where they shut it down. That’s brilliant. Do we know if any of the black students were admitted to the white schools?

Melissa: Okay, we know that Nathan attended, because in his diary, he tells how the teachers completely ignored him in the classroom. He was a non-entity as far as they were concerned. So, that’s a first-person account that he was not treated well by the teachers in the school. And he did attend the High Street School which was right across from his home. And also his younger sister, Alvarilla. They went through all of 1873 going to the board meetings, there were articles written in the newspapers, by March 20th 1873 was “Colored Schools Reported Abolished in Albany.” Then in 1873, there was the mention of the South Street School, which is where the school was located, and there’s still one of the walls extant, the late colored school so we know that it was after 1873, probably around 1876 that it actually was passed that the schools would be integrated in Lockport. And by 1877, the building was sold.

Lauren: So in looking at a broader context in New York State, trying to figure out exactly when schools officially were desegregated is a little bit convoluted, but I think we have to start back in the beginning with the 14th Amendment. According to historian David McBride, the 14th Amendment was: “aimed at extending full citizenship status and legal protection to newly emancipated Blacks by prohibiting states from depriving persons of due process and equal protection.” And shortly after this, in 1873, New York State was one of the first states to enact their own civil rights law. And this was happening at the same time that Aaron Mossell was in the middle of his fight to integrate Lockport schools.

Devin: The New York State Civil Rights Law established that no state citizen “on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude was to be excluded from the equal enjoyment of accommodations or facilities provided by: innkeepers, common carriers, theaters, or common schools and public educational institutions.” So why didn’t it work?

Lauren: While the Civil Rights Law of 1873 attempted to integrate all schools in New York state, there was a mixed reaction to this law. In some places, immediately school boards responded to this, notably: Albany, Newburgh, Geneva, Schenectady, and Troy allowed Blacks to attend public schools and closed down schools that were specific to black children. But there were others, notably larger cities like Brooklyn and Buffalo, that did not integrate their schools.

Part of the reason that this only worked in some areas was that there was an argument that local law preceded state law. And so if there were local laws enacted by the Board of Education or local municipalities, that those laws took precedence over this larger state civil rights law. And there were lots of court cases fought over this to try to integrate schools; a few of them successful, many of them not successful. And so we have a situation where segregated schools continue in New York state into in some cases, the 20th century.

Devin: There’s another important reason why the civil rights law of 1873 had limited impact. And that’s the Supreme Court case known as Plessy v. Ferguson, which happened in 1896. And really declared the “separate but equal” mandate, and basically said that states cannot force institutions or private entities to treat African Americans and whites similarly, that they were two separate entities. And as long as there was, for example, a black school and a white school, that was fine, as long as the black school was on par with the white school. And as we’ll see, that wasn’t necessarily true at all times, either. So you had Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which really weakened the Civil Rights Law of 1873. And gave local municipalities and local school boards the ability to say “we are providing a black school. So therefore, we are adhering to the Supreme Court’s Case.”

Lauren: It really wasn’t until 1954, with the court case Brown v. Board of Education, where the Supreme Court declared that “separate but equal” was not constitutional. And that was the official legal end of segregated schools in the United States.

Devin: And part of this is the reason why segregation of schools beyond legal segregation continues to this day in New York State. I’ll note a 2021 article from the Albany Times Union with the headline that says: “Nearly 70 years after Brown decision, New York schools still separate and unequal.” A lot of this article is based on a UCLA report that came out in 2014 that suggests that New York schools – to this day – are the most segregated in the United States for African American students, and the second most segregated for Latino students, only to California.

So why, after all of these decades after Brown v. Board, are New York schools still heavily segregated? Even though not legally so, but they remain heavily segregated. And that’s for a variety of very complex reasons. Certainly, racism is a big part of it. But also socioeconomic reasons. Redlining, which really barred, essentially, African Americans from settling in certain communities and only allowed them to buy houses or rent apartments in certain parts of cities or certain parts of counties. All of this played into why the schools remain segregated. But it’s also because of the distribution of resources. What we’ve seen over the decades is that the schools that are predominantly white in New York State, the per-student resources are much higher than predominantly minority schools. The state did attempt to rectify this situation in 2006, with the establishment of School Formula Aid, which was a formula that was supposed to balance socioeconomic backgrounds so that schools located in poorer parts of the state received more funding from the state than schools in wealthier communities. This has been problematic for a large reason because the state essentially withheld billions of dollars in Formula Aid during the recession of 2008 and 2009. Governor Hochul has declared that she will be distributing that funding – over $4 billion dollars – to school districts around the state. So hopefully that makes a difference.

An example of how segregation has worked in the 20th century in New York, is really the formation of predominantly white suburbs around the urban centers, including New York City with Westchester County and Long Island. Long Island is known as the birth of American suburbia, with Levittown and the establishment of the suburbs there, which were again, predominantly white. Again, there was redlining that did not allow African Americans to buy houses in these places. And as a result, you have white communities, and you have communities of color.

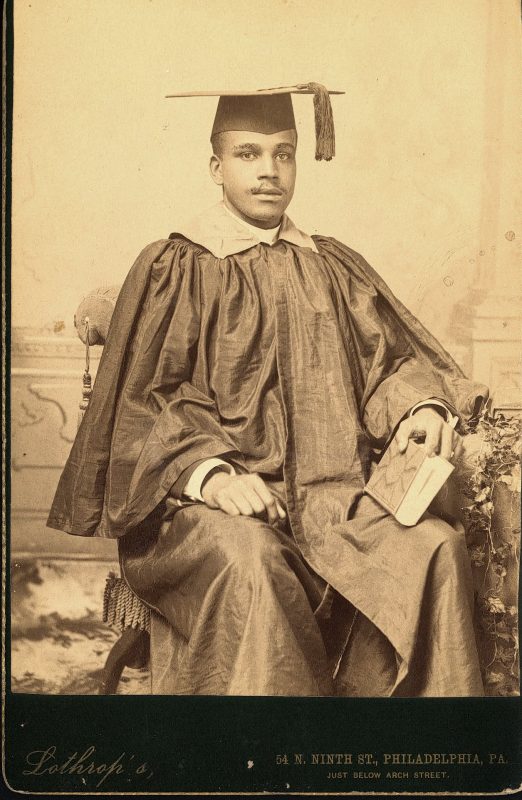

Devin: So Nathan became a physician,

Melissa: Yes.

Devin: Aaron, Jr. became an attorney, correct?

Melissa: Correct.

Devin: Charles was a Reverend.

Melisa: Also Charles was a missionary to Haiti. And then he authored the book on…

Heidi: Louie Toussaint L’Ouverture [sic], the leader of the Haitian Revolution. He wrote a book about his life.

Melissa It’s still the definitive book.

Devin: So it’s certainly a legacy of success.

Heidi: I mean, their achievements were pretty phenomenal. But the challenges and struggles were also as phenomenal.

Melissa: And it continues. I mean, their level of education and achievement continues, generations later.

Lauren: Aaron’s children create a legacy for the Mossell family that is truly amazing for any family. His son, Nathan, went on to become the first African American doctor to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania; he continued on to create the first African American hospital in that city to treat specifically African American patients. [Aaron’s] son, Aaron Jr. went on to become the first African American attorney to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania. And it even extends down beyond that generation.

Devin: Aaron Jr’s daughter, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, became the first woman to receive a PhD in Economics. She then went back to school and passed the bar and became a civil rights attorney who would go on to serve on three presidential commissions. There is an elementary school now named after her in Philadelphia.

Melissa: The Pomeroy Marker was part of a much larger project. We were trying to get the North Park School renamed because Aaron Mossell, his brickyard was actually on the property. It was the only elementary school in Lockport that wasn’t named for a person. It was just named for the location. And we thought that this was the perfect… we just thought it would be so easy! It was a no brainer! But no. There was some dissension in the community.

Heidi: I think an important thing is that I’m sure that a lot of those board members at the time probably didn’t even know who Aaron Mossell was.

Melissa: What we wanted to do was bring attention to not only integration, but also the entrepreneurship of the family. So the marker was part of it. There’s now going to be a park, the Aaron Mossell Park, and we were also going to do a trail because he donated so many bricks for different buildings, all the way up into Hamilton, Ontario. That was why we started this whole project and why we got the marker.

Lauren: While Aaron Mossell’s name was very prominent while he was alive. It seems that the city, as often happens, has forgotten his name. In 2011, the idea of renaming the North Park School came about to honor Aaron Mossell. This was a long-duration effort by members of the community to recognize Aaron Mossell’s commitment to education, and to bring his name back to prominence by having his story more broadly known, especially by schoolchildren in Lockport. As part of this effort, Melissa applied for this William G. Pomeroy-funded marker to help bring awareness to the Mossell’s story. And that’s part of the reason they chose to put this in a public place where there would be more foot traffic and the name would earn more recognition. And not unlike Aaron Mossell’s story, they were also successful after a decade of fighting to get the school renamed The Aaron Mossell Junior High School.

Melissa: Now, instead of just saying the location name of the school now we’re telling the story of the person.

Lauren: Bringing these lesser known stories to light within communities is one of the most important things that public historians do. We all have stories like this within our communities. And it is the job of municipal historians and historical societies to find these stories and bring them back to the surface.

Devin: The story of Aaron Mossell Sr and his family and the integration of the Lockport schools is again an important story in and of itself. They were ahead of their time, they used civil disobedience in a way that was successful, that engaged the rest of the community, they were able to access the white school for their children. And as we’ve spoken about, this has led to a long legacy of educational achievement. It was really the result of this struggle, where Aaron Mossell said: “My children deserve the same opportunity for education that anybody else’s do.”

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, with help from intern Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.