On this week’s 51%, we recognize Women’s History Month. We learn about Sarah Smiley, a controversial Quaker minister who dared to preach to women — and men — in the 19th Century, and Nancy Brown of the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites provides a more local lens on the women’s suffrage movement. We also stop by the New York State Museum to learn about a new initiative to expand its collection on women’s sports.

Guests: Samantha Bosshart, executive director of the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation; Nancy Brown, National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites; Ashley Hopkins-Benton, New York State Museum

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.

Follow Along

You’re listening to 51%, a WAMC production dedicated to women’s issues and experiences. Thanks for joining us, I’m Jesse King. All month long, we’ve recognized Women’s History Month by taking the time to learn about prominent American women, past and present. At the end of each episode, we visited exhibits at the New York State Capitol and spoke with the National Women’s Hall of Fame. This week, I wanted to take a more local approach — mostly because, as a transplant in Central New York, I’m forever catching up on my Capital Region history, but also to serve as a reminder about the wealth of history that’s right in our local communities. We’re also flipping the script this week — rather than ending with a “woman you should know,” let’s start with one.

At the end of last year, the city council of Saratoga Springs, New York, unanimously voted to designate a small cottage on Excelsior Avenue a local landmark. The Smiley-Brackett Cottage, as it’s called, is thought to be a prime example of the Gothic Revival style of architecture popularized by Andrew Jackson Downing in the 19th Century — but it’s also noteworthy for those who lived there. The house was owned by and built for Sarah Smiley, a popular, yet controversial Quaker minister.

“She really had this significant impact, I think, on women and public speaking,” says Samantha Bosshart, executive director of the Saratoga Springs Preservation Foundation. The Foundation led the effort to acquire the local landmark designation.

Smiley was born the daughter of a well-known Quaker family in Maine in 1830 (her father and brothers would go on to build the popular Mohonk Mountain House resort in the Catskills, which still operates today). She initially sought to become a teacher, but after the Civil War, Bosshart says Smiley went South to “relieve human suffering.”

“She traveled to Virginia and to North Carolina, aiding Quakers in organizing schools and libraries,” Bosshart notes. “She helped to start a school for 1,000 free Black adults and children in Richmond, Virginia — but that’s not really what made her well-known. She later spoke to what they called ‘mixed audiences,’ and when we say ‘mixed audiences,’ we’re talking about men and women. Women did not speak in front of a congregation, that just wasn’t happening.”

In 1872, popular minister Theodore Cuyler invited Smiley to preach before a mixed congregation at the Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn — making her the first woman to speak from a Presbyterian pulpit.

“This caused a ruckus,” says Bosshart. “This made Harper’s Weekly news, and she was said to ‘teach and to extort, or to lead in prayer in public and promiscuous assemblies…[it’s] clearly forbidden to women in the Holy Oracles.’ But what we learned, or what I learned after that, was that she was so well-received amongst her audiences that she was asked to speak across the country and abroad.”

Soon, Bosshart says Smiley was speaking in churches from Cincinnati, to London, to Cube. She was adamant that women could study the scriptures themselves, without the help of men. She started a home Bible study program for women, and would go on to write five books on the subject — some of which are still published today.

Bosshart says Smiley’s Gothic-Revival cottage was built the same year of her notorious appearance in Brooklyn. She’s not sure why Smiley chose to settle in Saratoga Springs, but it appears she knew exactly what she wanted in terms of a home.

“Andrew Jackson Downing, he published his Cottage Residence in 1842, and The Architecture of Country Houses in 1850. Alexander Jackson Davis designed and drew the illustrations featured — her house looks nearly identical to one of those cottages. Perhaps because it was the gothic style that is reminiscent of churches, perhaps [she was] being influenced by seeing these rural cottages, and she wanted it to be in keeping with that,” Bosshart adds. “She would come to Saratoga to study. In an article in 1874 in The Saratogian, it said, ‘She speaks twice almost every day in the week. She only spends six months of the year in preaching, the remainder of the year, during the summer months, in diligent study in her cottage in Saratoga.’ So I think, perhaps, it was where she had peace and quiet.”

Following Smiley’s death in 1917, the cottage was left to The Society for the Home Study of Holy Scripture and Church History, the group she had founded to promote religious study by mail. It was ultimately bought by another famous name who owned the property until 1968: Charles W. Brackett. Brackett was a popular author, New Yorker drama critic, and screenwriter of films including Sunset Boulevard, The Lost Weekend, and 1953’s Titanic. In 1958, he received an Honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement.

Bosshart says the cottage ultimately fell into disrepair following Brackett’s death. The building is privately owned, so she notes there’s nothing the Foundation or city can explicitly do to restore it at this time, but she remains hopeful that they can work with the owner down the line. In the meantime, the Foundation is celebrating the local landmark designation, which requires a review for any demolition or new construction in the future.

“I think it’s important that we continue to recognize all the people that contribute to the stories of our communities. Having an opportunity to be a part of ensuring that Sarah Smiley’s story is told and preserved is rewarding,” says Bosshart.

Saratoga Springs, as it turns out, saw many aspects of women’s history. When we talk about the Women’s Suffrage Movement, we tend to start with the Seneca Falls Convention and Declaration of Sentiments in 1848 — but as our next guest will tell us, there’s a lot of local history to the movement, including in Saratoga Springs.

Nancy Brown is a board member of the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites, and chairperson of the National Votes for Women Trail, a database of more than 2,000 sites significant to women’s suffrage across the U.S. She says the goal was to highlight the nationwide, grassroots commitment that was needed to gain women the vote, and honor the ongoing struggle for voting rights across the U.S.

How did you get involved in the National Votes for Women Trail?

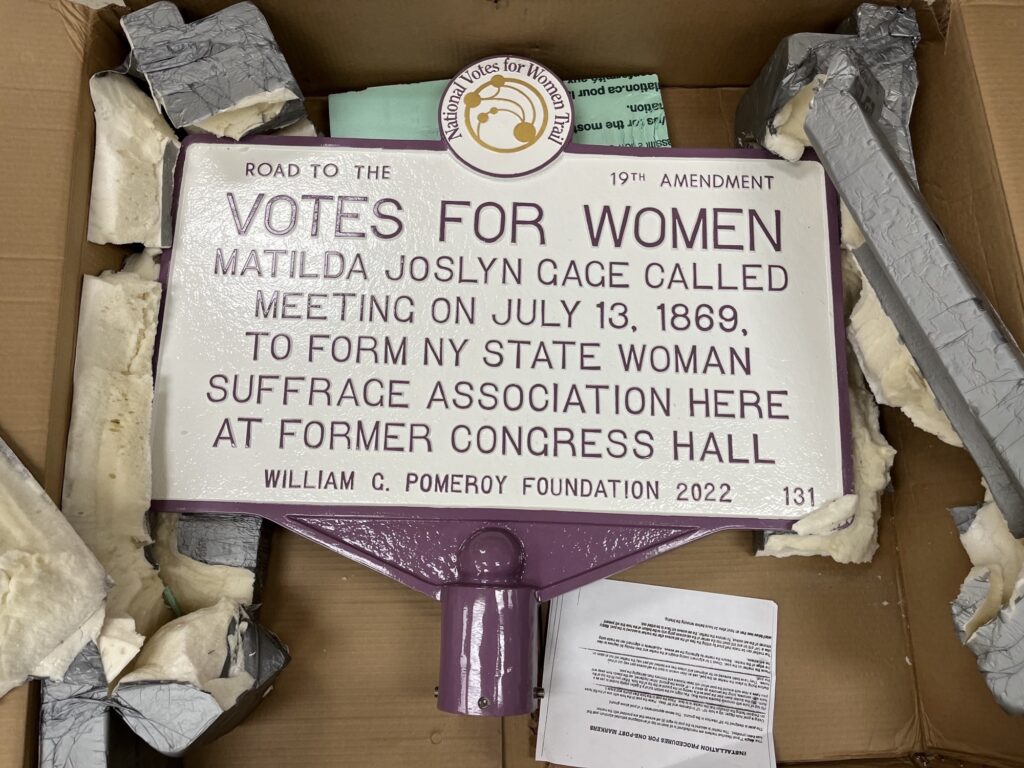

I think that my interest in women suffered comes from the fact that I’m a native of Johnstown, New York, and that is home to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, where not only she was born, but inspired. So I think that has always made me very interested in women’s suffrage. I was a board member on the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites, and this became a project that was originally, actually, a funded project that was proposed by Hillary Clinton – to have a Votes for Women Trail. And it was passed, the legislation was passed, but there were never any funds appropriated for it. So I remember being on a phone call, years ago now, and we were bemoaning the fact that there was no money to tell the story of women’s suffrage – how half of our democracy became enfranchised, which is a pretty huge story. And we got thinking that really, suffragists we’re all volunteer operations. So that’s how the National Votes for Women Trail got started: a number of volunteers stepped up and we ended up creating a national network. And our goal was to have 2,020 sites on a database, a mobile friendly, searchable database by 2020 – which we exceeded, and we’re now at 2,300 sites, it at nvwt.org. And along the way, the William G. Pomeroy Foundation in Syracuse, New York, recognized the importance of the project and offered to fund historic markers for places of specific significance around the country. And they are doing that for over 200 markers. So it was through that project that I kind of stumbled across the wonderful suffrage history in Saratoga.

So what role did Saratoga play in the women’s suffrage movement?

Well, I will tell you how I stumbled across it, to be honest with you. One of the most important and influential associations was the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association. And when I was doing a little research on where it started, I realized that it started at a meeting in Saratoga in July of 1869. Matilda Joslyn Gage, who was famous suffragist from Syracuse, actually had called a meeting to form a state women’s suffrage association, and it was held at Congress Hall, which is where the corner of Congress Park and Spring Street is in Saratoga. And it was chaired by Susan B. Anthony. And the result of it was the formation of the New York Women’s Suffrage Association. Why that’s so important is this will become the association that helps women win the right to vote in New York state, which happened in 1917. They lost the bid for voting in 1915, but were able to get it in 1917. And why that’s so important is we were the 12th state in the nation to pass women’s suffrage – but the other states were in the West, and we were the first state in the east to pass this. And Carrie Chapman Catt, the famous suffragist, called this the Gettysburg of the woman’s suffrage association. So come to find out that started right in Saratoga. And when I looked back a little further, I found that that was not the first women’s rights convention in Saratoga. Well, we know that the very first one was in Seneca Falls in 1848, that sort of began the idea of having women’s rights conventions. And after that there was one in Rochester, but in 1854, actually – the suffragists were such strategic thinkers that there were some other associations meeting in Saratoga, and they decided to go to Nikolas Hall, which was on the corner of Phila and Broadway. And they had a meeting with Susan B. Anthony, and it was very well regarded, very well attended. It was before there was a race track, but still, it was very popular place to go for people who had money and influence, and they knew that that’s what the suffrage movement needed, was money and influence. And they had another meeting again in 1855, because it went so well. Then they have the meeting in 1869, in Saratoga, that forms the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association, which becomes so influential. And then what I think is so incredibly interesting is the last meeting of the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association was held there in 1917. And that was the last one before the vote, and then fortunately, the vote was passed and women got the vote within our state. And that’s a really interesting meeting. That is sort of a culmination of all the work that the Association had done throughout its history, and they had really won over all the legislators. They had worked during World War I, doing all kinds of anything that was asked of them. They had worked with the state military census, they had organized Red Cross chapters, they had sold bonds, they had organized food canning clubs, and every political party decided that they were going to support them. And it was quite a meeting. Even Woodrow Wilson wrote a letter and said, “I look forward to seeing the results of the meeting in Saratoga.” And it started out with a car parade, an automobile parade from Buffalo across the state to Saratoga. So that was August 1917. And hundreds of cars were coming down Broadway. And that’s when about one in four people owned a car, so that must have really been quite a sight. And again, famous people like Woodrow Wilson wrote a letter, Samuel Gompers wrote a letter of support. Katrina Trask sent a letter saying that she supported suffrage and wanted to make a donation that would have been worth about $5,000 in today’s money. So it was really quite an interesting place. I think what’s especially interesting about it is it was a turning point, literally in the suffrage movement nationally. And Saratoga is known as the turning point of the Revolution, right? We all know that the American Revolution, and that enfranchised white men, essentially. But it was really a turning point in what many people have called the “bloodless revolution,” which was the 72-year-fight for women’s suffrage over which no blood was shed, and voting rights were gained. So I think that its importance is very significant.

You mentioned you’re from Johnstown, and that’s where Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born. And you also said it’s where she was inspired. Can you go into what you mean by that for me?

I sure can. Elizabeth was one of the children born to Judge [Cady] and his wife, and unfortunately, only one of their sons made it to adulthood. Eleazer. And when he came home from Union College, he passed away at the age of 20. And Elizabeth remembers in her autobiography, that, as her father, who saw this as the successor to his law practice, was sitting by the coffin, he was just despondent. She went, and she sat on his lap, and he said, “Oh, Elizabeth, if you’ve only been a boy.” And apparently after that, she talked to her neighbor, who was the Reverend Simon Hoosick, and asked if he thought boys are better than girls. And he said, “No, of course not.” And she vowed at that point in time that she was going to become as good as any boy. And she became a very good horse woman. And she went to the Johnstown Academy, and was in all the accelerated classes that very few girls were in. And there was a coveted Greek prize, that she won along with another gentleman at one point, and the story goes that she took that Greek prize, which was very coveted, and she ran it down the street, and she went to her father’s law office and said, “There, I won the Greek prize.” And he said, “Elizabeth, if you’d only been a boy.” And because her father was a lawyer, and we believe that his law office was adjacent to their home, she spent time there and she learned about the law. And she learned how the law didn’t favor women. And there’s the story of a woman who came to see the judge, because she had no property rights, and her husband passed away, and her son and his wife were kicking her out of her house, and she had no rights to stay there. And Elizabeth heard this story and vowed to cut all the laws out of his logbooks. And he said, “Elizabeth, you would have to go and talk to the legislature to change a law,” never really realizing that she really would end up doing that one day, and she would help change the property law in New York state. So she really was inspired by the events of her youth that took place in Johnstown.

You mentioned when you were describing the conventions that there’s parades of cars and famous figures and big donations being made for the effort. Do you see it as a movement that, at the time in Saratoga, was particularly driven by the upper classes, or was there a movement for the everyday folks who wanted this too?

I think that when we think about it, and we look at the suffrage movement in New York state, for example, there were women like Rose Schneiderman, who worked so hard for workers’ rights as well as for suffrage, knowing that that would help the workers gain a voice in their destiny. But I also think women who had more money had more time to devote to this. And there were certainly women who were immigrants who were very interested in this and worked in suffrage, but they had so much on their plates just to survive and just to get educated and just to keep their families together. But there also were Black women who worked so hard to win the vote when the suffrage movement was not always kind to women of color. So there were really women of every class who worked terribly hard, and devoted themselves to a cause that they didn’t even know if they were ever going to see. So I’m so impressed by that as well. And fortunately, I will say that the National Votes for Women Trail has worked hard to try and unearth as many stories as we could for those underrepresented women who aren’t known as well as the upper class white women, who we tend to know their names.

I was going to ask, as we’re looking towards preserving sites that have to do with women’s history, what are some things that we should keep in mind? And what are the obstacles that are we’re running into nowadays to create more monuments to women in the U.S.?

Well, the obstacles in terms of preserving sites are they weren’t preserved, unfortunately. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s original house, for example, was moved, and a new one that she lived in was built out of stone, because there have been a number of fires in Johnstown. And it was taken down in 1963. And nobody thought a thing about it, actually. And she was a woman of means, so her family had some money. And that’s why we on the National Votes for Women Trail are willing to mark sites, because so many homes, nobody preserved the history of them at all. And especially those that women of color [lived in], they’re particularly hard to find. Before those names get lost, it’s really our responsibility to do our best to shine a light on the information that we can find in for those few remaining places. Like fortunately, Katherine Starbucks’ home is still there. So that’s why it’s so important to recognize it. Because so many of these homes in locations really are not. It’s just, you know, ideally that that people really take some time and do their research. They can go on the National Votes for Women Trail and submit sites in their community, if they find information. We then have somebody who reviews them before they’re released to populate the map. But we I just think, fortunately, with the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, there was more interested in women’s history. And I think people are more interested in finding out who was in their communities that help them get the rights that they enjoy today. And we also need to be mindful of, you know, all women couldn’t vote in 1920, Black Women’s still had a long way to go to fight their way through Jim Crow laws before they could vote. And, you know, Native American women weren’t even US citizens yet, not for another four years and women of Asian descent. Not until even after that they were not citizens yet, so they didn’t get the vote. And as we know, unfortunately, today, voting rights are still being compromised in a variety of places. So I think that is equally important to commemorating their sites, I suppose is commemorating their struggle for the for the right to vote.

Well, lastly, in looking at the local impact on women’s suffrage movement, what has been your main takeaway?

I think the main takeaways – I didn’t know any of that history existed there, either. But in every county in New York state, there was an active women’s suffrage association. That’s how they were able to eventually get the New York state legislature to pass the amendment to the law so that they could vote. But so I think what I have learned is how widespread it was, how many people had to be involved to get this movement over the finish line, if you will. Also, there was a significant anti-suffrage movement that I wasn’t aware of before I started doing research. And there were women as well as men who didn’t think women voting was a good idea. They thought that they didn’t need to vote to make their voice heard. If you dial it all the way back to that first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton said in her Declaration of Sentiments that she felt that women needed the right to vote, almost no one agreed with her then. They said, “Oh, that’s too much. You know, we can’t go quite that far.” But it was Frederick Douglass who stood up and said, “No, she’s right. Without the right to vote…that’s the right by which all other rights are gained.” It really was such a Herculean effort. There are so many people that we don’t know about, that we should be so grateful for. I think there’s so much research to do and so many people we need to try and remember their names and try and find out about them so that their efforts won’t be lost.

Nancy Brown is the chairperson of the National Votes for Women Trail. You can view the trail and learn more about a site near you on the website for the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites. The William G. Pomeroy Foundation has a map for all of its historic markers at wgpfoundation.org.

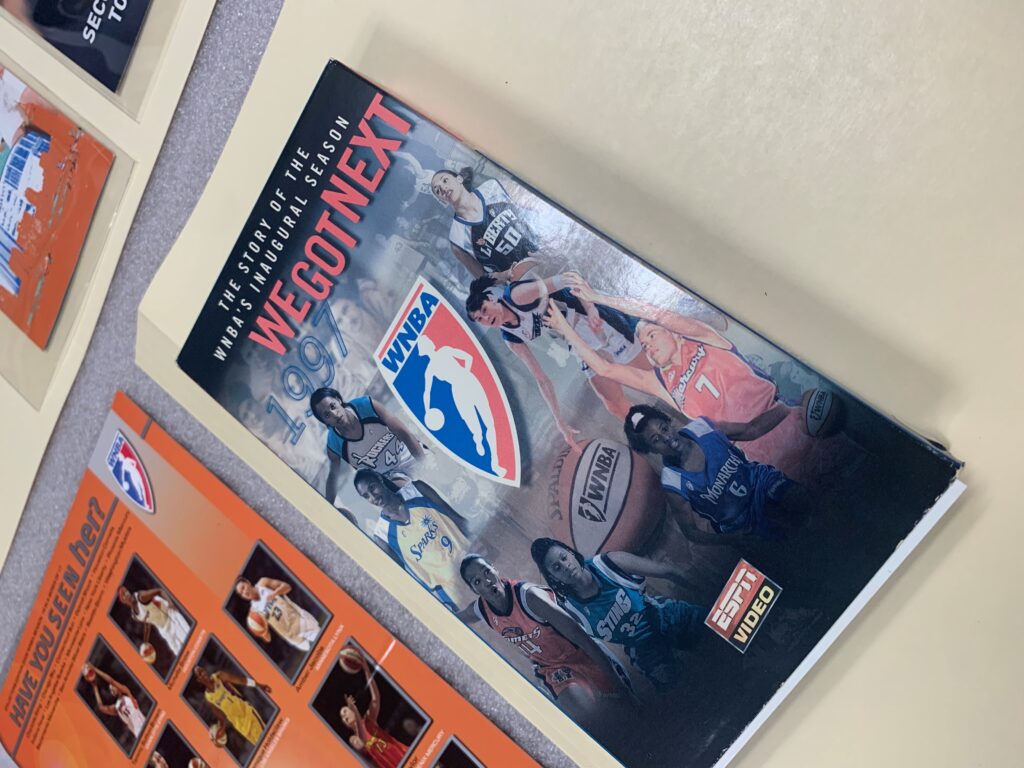

Lastly, on the topic of preserving women’s history, the New York State Museum in Albany has launched a new effort to expand and diversify its collections — specifically, its sports collections. It’s all ahead of the 50th anniversary of Title IX this June — Title IX, of course, is the federal civil rights law prohibiting sex-based discrimination in schools that receive federal funding. It applies to all aspects of education, but one of its most visual impacts was in sports, requiring schools to equally support girls’ and boys’ teams. The museum is trying to balance out its own recollection of sports history by recognizing juggernauts like the WNBA’s New York Liberty, or special events like the all-female Aurora Games, which launched in Albany in 2019.

I spoke with the museum’s senior historian and curator for social history, Ashley Hopkins-Benton, to learn more.

“At the New York State Museum, our entire history curatorial department has been working on really evaluating our collections, and what strengths we have, and also what stories we’re missing,” says Hopkins-Benton. “And diversity, of course, is always something that we’re trying to get more into the collections. But a couple of years ago, in 2017, when we were working on the Votes for Women exhibit about the centennial of women’s suffrage in New York state, we realized women’s history collections were really lacking. And then shortly after that, Steve Loughman, who is our sports curator, also was realizing that sports were really lacking, which is crazy when you think about New York and all of the great sports teams and sports stories that we have. So simultaneously, we were both working on these things. And because of the upcoming anniversary of the passage of Title IX, it became very apparent that women’s sports were a particular collection that was lacking.”

So what kinds of items are you looking for in this collection?

Well, let me start with what we have, because it’s very small. It’s all out on the table in front of us right now, we really have two collections that speak to women’s sports as they relate to New York state. So one is a collection of material from the New York Liberty basketball team, the WNBA team. And this came in from a woman named Pam Elam, who is a feminist and a women’s history scholar, and was really interested in collecting women’s history and LGBTQ history as it pertained to culture and politics and sports and everything. So this came in before we even knew that women’s sports was something that was missing from our collections, and it includes tickets and calendars and bios of the players. So it’s a really great snapshot of the league. And these all came from around 10 years of the league being in existence. So that was the first thing that we had. And then a couple years ago, when Albany hosted the Aurora games, a couple of us all went out to different events and collected pins and basketballs and shirts and other materials from that. So that was a great opportunity as well. So we have two examples, more on the professional sports side of things. But we would love to collect more amateur sports, girls playing in high school, women in college, and those stories. I’m definitely looking for stories of trailblazers, women who were the first to play their sports. New York has so many great stories of girls who play on their high school football team, or I spoke to a woman earlier who was the first girl in her high school to earn a letter by playing on the men’s golf team back in the ‘60s. So I am also looking to speak to women. I’d like to do some oral histories of women who were involved in sports at various times in history.

Cool. Now, if someone has something that they think might be a good addition to the collection, what is the process of giving that to the museum?

Well, reaching out to the museum and to me in particular, and then I bring it to our collections committee, and we discuss it as a group – how it fits into the collection, if it’s something that we can responsibly take care of, and if it’s something that has research and exhibition value in the future.

If you think you may have something you’d like to contribute to the collection, you can find more information at the museum’s website. You can also email Ashley Hopkins-Benton at [email protected]. Title IX turns 50 on June 23.

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.