On this week’s 51%, we discuss the inflammatory condition endometriosis: what it is, what it looks like, and how it’s treated. We also speak with Linda Griffith, scientific director of the MIT Center for Gynepathology Research, about how engineers are working to better understand the disease.

Guests: Linda Griffith, scientific director and co-founder of the MIT Center for Gynepathology Research; Dr. Kathy Huang, director of the NYU Langone Endometriosis Center; Sarah Digby; Natalie Rudd, learning and education manager at the National Women’s Hall of Fame

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.

Follow Along

You’re listening to 51%, a WAMC production dedicated to women’s issues and experiences. Thanks for tuning in, I’m Jesse King.

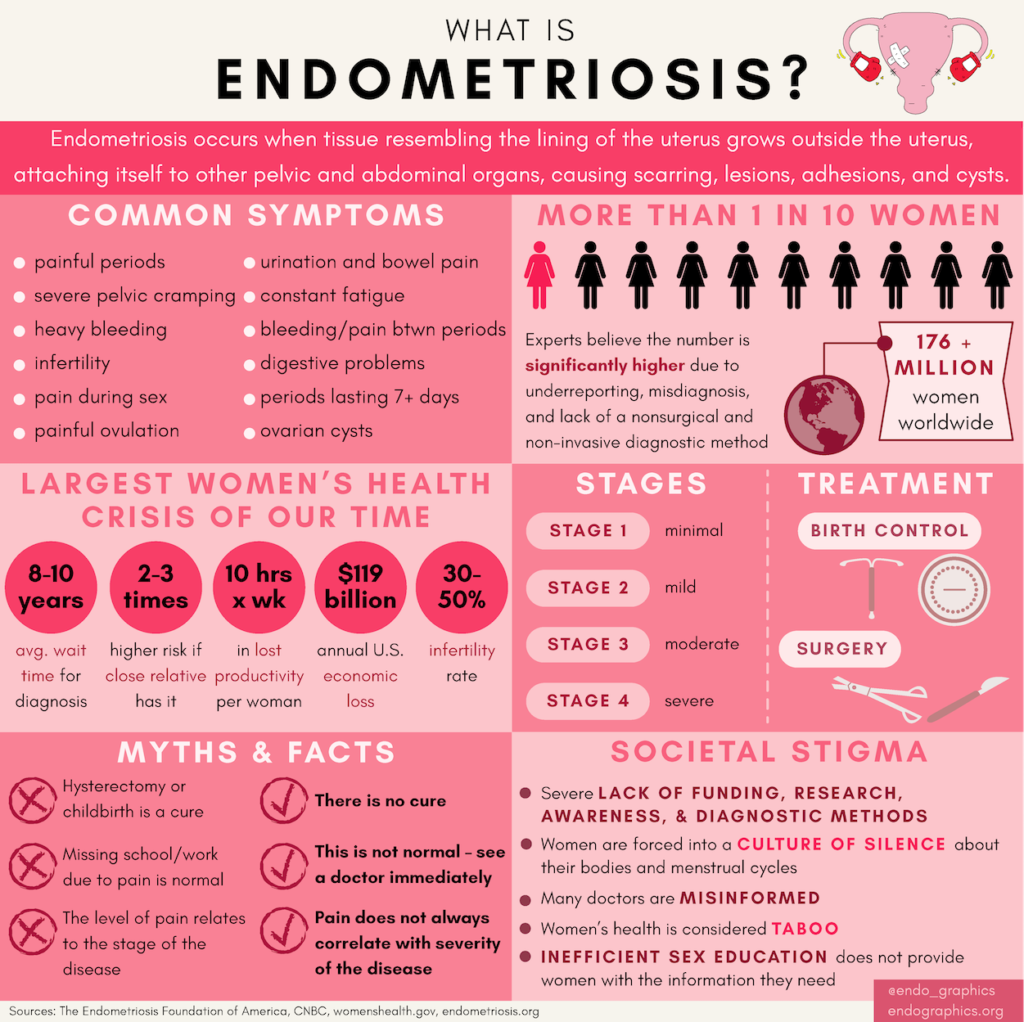

Most of us are aware that it’s Women’s History Month, but the month of March is also an important time to discuss women’s health. It’s Endometriosis Awareness Month, a time to read up and spread the news on a condition that impacts roughly 1 in 10 women (or people with uteruses) worldwide. Despite those numbers, endometriosis has historically been written off as a “women’s disease,” a taboo topic of conversation, or simply part of being a woman in general (after all, no one enjoys their period) — so there’s still a lot we don’t know about it. So that’s what we’re focusing on today. The big questions: what is it, what does it look like, and how is it treated.

To use the definition offered by the Endometriosis Foundation of America: endometriosis is when tissue similar to the inner lining of your uterus, called the endometrium, is found outside your uterus — where it shouldn’t be. Typically, endometriosis is found on organs like the uterus, the fallopian tubes, ovaries, bladder, etc., but in extreme cases it can advance outside the pelvic cavity to other areas, like your appendix or even your lungs. The problem is that this tissue still acts like the tissue inside your uterus, so it bleeds with your monthly menstrual cycle. This can result in painful inflammation and lesions that contribute to symptoms including: painful and abnormal periods, bowel and urinary issues, neuropathy, infertility, and more. Currently, there is no cure.

Our first guest today is Sarah Digby, a 32-year-old former education specialist now living in New York City. Digby grew up in San Antonio, Texas, where she says her access to sex education was extremely limited. Even at home, it wasn’t typical for her family to talk about their bodies, so she grew up knowing very little about her own. But the moment she started getting her period at age 12, she knew something was off.

“The way that I was experiencing periods, the way that I was bleeding, and the amount of pain that I was in — it was nothing I had been led to expect I would experience from the pre-teen magazines I’d read, and what cramps would feel like,” says Digby. “They would be really bad the first couple days of my period — and I had long periods, they lasted about seven or eight days. They’d kind of abate, and then I’d have some pain towards the end…How could something so painful be so accepted and natural? Even though that’s what people were telling me. To be fair, I was a dramatic teenager — but I was also in a lot of pain.”

Digby says her period caused her to routinely miss school during her high school and college years — but that didn’t seem to concern many of the people in her life. She never got used to the pain, but over time, Digby says she basically learned to live around it, or at least, in her words, “shut up about it.” By the time she moved to New York and started seeing a new OB GYN in 2008, and it didn’t even occur to her to mention the regular pain she was experiencing.

But the cysts started happening.

“One of them happened on a plane, right before takeoff, while I was on a layover. I passed out and had to be pulled off the plane by EMTs. Even then, no one could figure out what was wrong,” Digby explains. “At the time I was actually a teacher, and one time I had an endometrioma rupture on the subway — didn’t know that’s what it was — [I] barely made it into the school, and then [I] had to have someone cover my class, because I was down for the whole rest of the day, unable to walk, unable to do anything, and just in excruciating pain. I was quickly becoming pretty disabled.”

What Digby was experiencing were rupturing endometriomas, blood-filled cysts that typically start on one or both of the ovaries. Endometriosis is currently classified in four official stages according to morphology — basically, how many lesions or cysts you have, and where they are. At the time, the flare-ups around Digby’s periods had died down — she was on the IUD, so she stopped getting her period — but over time her lesions had increased in number and gotten deeper, and with the added cysts now bursting multiple times a year, her pain was no longer tied to her menstrual cycle. It could hit at almost any time.

A precautionary sonogram by Digby’s OB GYN showed an unruptured endometrioma on her right ovary, which then prompted her doctor to schedule a laparoscopy, or diagnostic surgery. At age 26, nearly 15 years after experiencing her first symptoms, Digby finally had her diagnosis: she had Stage 3 endometriosis.

“Finally, some good doctors were able to identify what was going on,” she notes.

We’ll check back with Sarah Digby later on in the show, but before we head on, I feel like it’s important to ask — what causes endometriosis in the first place? As I mentioned at the beginning of the show, there’s still a lot we don’t know about this disease, and although Congress has increased funding for endometriosis research over the past couple of years, it’s still largely under-researched and under-funded compared to other conditions.

Our next guest is Linda Griffith, a top bio engineer at MIT and co-founder of its Center for Gynepathology Research — currently the only engineering lab in the nation to focus on endometriosis. In some ways, Griffith’s story is similar to Digby’s: she’d always had painful periods, but it took decades for her to actually get a diagnosis. Even then, she required several surgeries to combat the disease (including a hysterectomy), and in the late 2000s she founder herself watching her niece begin to grapple with the same obstacles and frustrations. So in 2009, Griffith co-founded the CGR with the goal of better understanding endometriosis, so that it can be more quickly diagnosed and more successfully treated.

How does the CGR approach its research on endometriosis?

What struck us at the time we started to work together was the incredible diversity of patient presentations of endometriosis: the age of onset, the symptoms that they have, the types of lesions, the geographic locations of lesions, co-morbidities, response or not to drugs that are already available. After we started working together, I got breast cancer, and I was immediately classified on a molecular basis as triple negative. So there were three markers, they were related to the mechanism of cancer, to the prognosis, and to the therapies. Why is there not a molecular classification for endometriosis? It’s so prevalent. There’s got to be different molecular subtypes. So the approach at the CGR became “How do we start to classify patients by molecular mechanism?” with a hypothesis that patients could be different, sort of like cancer patients are different, and need different therapies and have different prognoses. So that was our starting point, and this was really, really not done at the time we started.

In doing that, we published the first two studies describing approaches to molecular classification. They’re not definitive, they were small patient samples, but this has sparked other people to be thinking in this way as well. And it’s something that we continue to pursue, both by looking at patient samples, but also by building little, what we call “avatars” of the patients. We take their tissues back to the lab, and we make 3D tissue, engineered little mimics of the patients, and then we can start to test whether molecular things we find in our analyses allow us to intervene with drugs that are not currently in the clinic. So it’s really this idea, which was novel, and now more people are thinking that we need to classify patients, because we know that they’re not all the same, and we need to figure out how new drugs that are not hormones, for example, could work in different groups of patients.

Do we know for sure what causes it in the first place?

The causes of endometriosis are highly debated and speculated on, and we don’t really know if there’s one cause. I tend to think there’s many causes. It’s like if a patient shows up in the emergency room and has a smashed tibia: it could have been a motorcycle accident, it could have been a brick falling on him, it could have been somebody hitting him with a baseball bat, etc. So there could be many things that converge on similar symptoms, and this falls in with our molecular mechanism hypothesis. There’s very, very interesting data supporting many hypotheses about developmental defects. Very clear data that’s support for some patients that, during development, cells can go out of the way and get the wrong place. There’s very clear circumstantial evidence supporting Sampson’s Theory. Some people really reject this theory, but it’s not been proved wrong, and there are many, many circumstantial supports for it — where most women have reflux of menstrual tissue during their periods, and it goes in the abdominal cavity. Most women will clear it, but it’s conceivable that some of that tissue implants and turns into lesions. That theory is not very consistent with onset at the time of monarch — we know that some girls, including myself, including my niece, had symptoms from my very first period, before there was all of this reflux. And so then there’s a hybrid around the time that babies are born. In some babies, there’s a little bit of bleeding seen coming from the vagina, and it’s about 5 percent of babies, tending to be babies born late. So there’s a hypothesis that there may be bleeding, shedding of the endometrial lining around the time of birth, because you have a huge fall in progesterone — and maybe that seeds the abdominal cavity with cells that came from the endometrium around the time of birth. And then when hormones surge during puberty, it wakes those cells up and they cause lesions. I think that there’s credible evidence in all of those arenas.

The interplay between infection/environmental exposure is still very much provocative, and circumstantial and epidemiological data suggests, for example, exposure to dioxin [could cause endometriosis]. Animal studies implicate exposure to environmental chemicals. This may be something that affects your immune system, and now your immune system is unable to clear the tissue that goes into your abdominal cavity. So many theories, and probably many of them are correct. There’s probably many causes.

Does the location of endometriosis have an impact on what you experience?

So there’s not a strong correlation between lesion morphology — meaning how big the lesion is and where the lesion is — and symptoms. Some patients can have Stage 4, lot of lesions, big lesions, deep lesions…and have no symptoms. And I know people like that. Other patients can have one tiny lesion and be in crippling, excruciating pain. Now, those patients may also have things going on with adenomyosis, and if you haven’t heard about adenomyosis, it’s important to bring it up. It is when endometriosis is in the wall of the uterus, in the muscle. And you don’t see it during surgery, typically, and you can infer it by doing an ultrasound or MRI of the uterus — but there’s no for-sure diagnosis other than hysterectomy and pathology, or some other interventions that involve surgery of the actual uterine wall. So some patients who are told they have Stage 1 [endometriosis] and feel like they have a lot of symptoms may have something else going on in the uterus, that’s actually a version of endometriosis that not a lot of doctors look for. We know very little about adenomyosis. Just for calibration, Crohn’s disease affects about 1 percent of the U.S. population, and in PubMed, where all the scientific papers are collated, there are listed about 60,000 papers for Crohn’s disease — which is great, it’s a terrible condition. But if you look up adenomyosis, which may affect about 10 percent of women, so that means about 5 percent of the population, or definitely more than 1 percent of the whole population, there’s only about 3,000 papers. That that’s for the whole world. So now you’ve got 5 percent of the number of publications for a disease that afflicts a lot more people. So this just tells you how little, you know, attention has been paid to gynecology at the level of funding agencies.

What do you feel are some of the biggest misconceptions about endometriosis?

Fortunately, many of the misunderstandings are being addressed through greater awareness and things like this. There is something that is troubling to me as a scientist, and as a patient, that I see on Facebook groups. There’s a particular Facebook group, “Nancy’s Nook,” and there’s a rejection of the idea that Sampson’s hypothesis, the reflux, menstrual tissue, is valid. A complete rejection of that. And I can understand that we want to highlight that there could be other causes, and I believe there are other causes, but it’s unfortunate when you throw out a scientific hypothesis without a basis for throwing it out. And there’s a lot of misinformation now being promulgated by patients who feel that they know more than the average patient — but they know far, far less than the informed clinicians and scientists who work in the field, and they’re very dangerous, in my view, because they promote patients to go seek care from people who may be promising them things that are not true. So if you promise a patient that excision surgery will cure them, publish the data saying that you cure patients that way, and then then you can say that. So I’d say some of the big misunderstandings rights now are actually misinformation being given to patients about cures that are not backed up by rigorous data.

What do you feel about the different treatments that are out there for endometriosis? And do you have hope someday for a cure?

As for treatments right now, it really depends on the patient. Some patients respond quite well to hormonal therapies. A lot of patients respond, some patients get great relief from the Mirena IUD, for example. Other patients do need to have surgery, and in the case of surgery, there’s a lot of debate about this so called “ablation versus excision.” You absolutely need excision if you have lesions that go deep into the underlying tissue. Ablation is simply burning them off — and if they’re very superficial, ablation can be sufficient. However, you have to be very sure that what you see as a superficial lesion is not invading deeper into the tissue. And so I think that this is where there, again, is some confusion in the way that certain patients on social media are advocating for certain kinds of treatment when there are nuances. I would highlight surgeons who have done a fellowship supported by the American Association for Gynecologic Laparoscopy, [they] are going to be trained to do the most severe endometriosis excision surgery. People may say they’re doing excision, and if they’re not trained through a fellowship, then it’s a lot less clear that they were trained with all the methods that are accepted by the professional societies to do that surgery. You don’t know until the surgery happens, generally, what the patient’s going to present with, and a surgeon who is trained to do only ablation, if a patient presents with more severe disease, will typically sew that patient up and refer them to an excision specialist. So I think we need to be cognizant that there’s a spectrum of therapies that for today are adequate for a lot of patients, but some patients are still not served by those: either they have no access to appropriate surgeons; their disease has progressed to a very difficult state, even for really good surgeons; and they may have complex pain phenotypes. Changes in the brain can make the pain more severe and persistent, and this is not a fault of the patient, this is a consequence of the disease. And one of the things we’re doing is trying to work with pain specialists to start understanding differences in patients who have different kinds of pain processing in their brains.

How might learning about endometriosis help us better understand other diseases or vice versa?

There’s amazing opportunity to learn about other diseases, particularly the other chronic inflammatory diseases such as fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome. [As well as] some autoimmune diseases, because inherently, endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease — something is wrong with the immune system or the body’s response to tissue that’s displaced. There may be connections to infection, or exposure to certain things, or maybe genetics. And so by understanding the relationships between the immune system and the lesions in patients, we are gaining insights into other chronic diseases. For example, we have just started a chronic Lyme Disease study in collaboration with several others at MIT, and there’s some fascinating crossovers between what the Lyme Disease researchers see in the mice, and the potential for there to be uterine phenotypes due to infection. And so there may be, potentially, some links between prior infection and development of disease. We don’t know. There’s a publication in the field that suggests certain kinds of infections predispose patients to certain kinds of endometriosis, but this is all very early studies. These kinds of studies will inform, in general, our understanding of female immunology — which by the way, is very different. We have in our local area actually started a discussion group that meets every two months called Sex and Immunity, trying to understand the differences between the immunological responses in men and women to infection and to vaccinations.

Once Sarah Digby was diagnosed with endometriosis, she eventually found her way to Dr. Kathy Huang, director of NYU Langone’s Endometriosis Center. Huang says her office takes a holistic approach to treatment, using MRI scans and ultrasound imaging to get a better sense of each patient’s individual case. She says the first-line of treatment includes hormonal suppression (including hormonal contraceptives), painkillers, pelvic floor therapy, mental health support, and even acupuncture. But as Dr. Griffith mentioned earlier, there are some cases where your options are limited: if you’re trying to conceive, then hormonal suppression isn’t going to be the immediate option for you. If you’re a more advanced case, like Digby, then some level of surgery — be it ablation or excision — may be necessary.

Huang says she specializes in robot-assisted, fertility-preserving gynecologic surgery.

“All of my endometriosis surgeries are done robotically, which means that it’s minimally invasive, it’s a small incision, and the patients will go home the same day. And what the MRI helps us with, is if the patient has endometriosis, where are the lesions of the endometriosis, so that if we plan for a surgical excision, we have the right partners in the room to do it, ” she explains. “So if the patient has endometriosis on the bladder, we will have a urology partner [in the room]. If the patient has significant bowel endometriosis, we may have a colorectal surgeon partner, so that we can do one surgery for the patient and have complete treatment for the condition, rather than multiple surgeries.

There are times that patients come in asking for a hysterectomy, which is the removal of the uterus. And I have seen multiple reports on patients undergoing a hysterectomy to treat endometriosis. And I think it’s really important to stress that, by definition, endometriosis is an extra-uterine disease. So removing the uterus itself is not going to help patients with endometriosis, unless the patient also has adenomyosis. That is the only situation where a hysterectomy will actually be helpful for the condition. The other that we talk about in fertility-preserving surgery is also not removing the ovaries. So the ovaries produce the hormones, and endometriosis is a hormone-responsive condition — however, if we’re able to preserve the patient’s ovaries, we do our best to do that, because it does continue to provide antigens even when the patient enters menopause. So it gives you hormones, it helps with your cardiac health, bone density, sexual health, all of those things. So it’s a fine line between doing definitive surgery, and stripping the patient of the ovaries and the uterus, versus symptom relief.”

Digby credits Huang and her gynecologists in New York for helping her get her life back. Through robotic excision surgery, Huang was able to remove more than a decade’s worth of lesions without damaging Digby’s pelvic organs, successfully bringing her from Stage 3 of the disease to Stage 0. While it could always come back, Digby says she keeps her endometriosis in check with regular monitoring and multiple forms of birth control (in her case: the arm implant and an IUD).

The whole process, from diagnosis to remission, took Digby just a year and a half — but she can’t help but wonder about those 15 years prior to her diagnosis. How might she have spent her 20s, if she had received treatment as a teenager? How much grief might she have been spared, if someone at home, her school, her college, or doctor’s office had noticed the signs? For Digby, spreading awareness is key to ensuring better treatment for future generations.

“Here’s something where, I think back, and it’s just wild: my mom had endometriosis. Never once did it occur to her, as she saw her daughter struggling with a gynecological disease, that there might be a connection there. Because she had been treated for endometriosis and had the surgery before my brother and I were born, but — and this not to say that this is any of her fault at all, the society’s falling — but she only had one or two symptoms, and they weren’t related to her menstrual cycle,” says Digby. “This is how this keeps happening from generation to generation. We all know what to do when somebody’s in diabetic shock: get them blood sugar. We all know what to do, or how to recognize, symptoms of a heart attack. And yet we don’t know, as a society, the most common symptoms of a debilitating disease in well over 10 percent of the female population, who could also benefit from that widespread awareness.”

“The one message I always have for women is that pain is not normal. So if your doctor is not taking you seriously, then you need to get a second opinion, because pain is never normal. And it doesn’t need to be endometriosis, there are other reasons for pelvic pain. We just did a study for sexual trauma, to see how often are OB GYNs actually asking women the question of, ‘If you have pain, is there any history of sexual trauma in your life?'” adds Huang. “I just think we need to talk about all these things more, it’s not just a single-lever problem. Even though I am a surgeon by training, I really don’t think the answer is surgery alone, and nor is it always the answer. It is only seldom the answer, and even when it is, it is not the entire answer. We still need other specialists to continue to help us, to help the patient. Again, the one message is that pain is not normal. So if your doctor is not hearing you, please seek a second opinion.”

If you think you might be experiencing symptoms of endometriosis or adenomyosis, Dr. Huang advises that you contact your OB GYN and then a specialist if needed. You can learn more about endometriosis and adenomyosis online. The NYU Langone Endometriosis Center, MIT Center for Gynepathology Research, and the Endometriosis Foundation of America all have info and even webinars on their websites to get you started. As part of her own effort to raise awareness, Sarah Digby has her own collection of easy-to-share diagrams and infographics at her website, endographics.org.

Before we head out, we’re celebrating Women’s History Month by taking some time each week to recognize prominent women in history. Joining me today is someone who’s been on the show before: Natalie Rudd is the learning and engagement manager at the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. More than 290 women, past and present, have been inducted into the Hall since its start in 1969, and Natalie has a couple she’d like to share with us today.

“She was a northern Piute author, actor, and activist. She was alive from 1844-1897, and she was raised by an influential Piute family in Nevada. For her, being American was a really complicated process, especially during the late 19th Century. It was a process of adopting the behaviors and languages of white people, who she had often been taught to distrust, but [she] had to do that to kind of assimilate and survive. She worked as a translator, which then eventually led to her becoming an activist for Native American rights. In 1865, her family was actually attacked by a U.S. cavalry, which killed 29 Piutes, including her mother and several members of her family, which then launched her into her advocacy for Native American rights. So she travelled all across the U.S., basically telling white Americans about the destruction and colonization of native peoples. She eventually worked for the U.S. as a messenger, an interpreter, and as a teacher for imprisoned Native Americans.

She ended up publishing a book called Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. The book is both a memoir and a history of her people during their first 40 years of contact with European Americans. It’s considered the first known autobiography written by a Native American woman, and then eventually she returned out west, where she founded a private school for Native American children in Nevada.”

“So Aimee has had a really cool career, in that she’s done literally everything. She was born with fibular hemimelia, which basically means she was missing her fibula bones, and as a result she had both of her legs amputated below the knee when she was one year old. She was told that she would probably have to use a wheelchair for most of her life, and probably never walk, but by the age of two, she had already learned to walk with prosthetic legs.

Aimee has always been about going above and beyond. She ended up becoming an athlete with her prosthetics. She got a full academic scholarship to Georgetown, and there she ended up pursuing a career at the School of Foreign Service. When she was there, she earned a top secret security clearance with the Pentagon at the age of 17. She worked there as an intelligence analyst as a teenager — which that alone is incredible. But simultaneously, she was running track and field for Georgetown, and went on to compete for the NCAA Division I track and field events. She was the first amputee student to ever compete in an NCAA women’s or men’s event. She later went on to compete in the Paralympics in 1996 in Atlanta, and she helped with the design of her prosthetic legs, which are designed after the hind legs of a cheetah. So a lot of the prosthetic legs you see now, she was involved with the design process of.

So again, that alone would have been amazing. After she retired, she then went on to be a model. Not only doing print, but also runway modeling. She modeled for Alexander McQueen, Kenneth Cole. She was named one of People‘s 50 most beautiful women in the world. And she’s also worked as an actress in both television in film. My favorite role of hers was she played Eleven’s mom in Stranger Things.”

Natalie Rudd is the learning and engagement manager at the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. The Hall will be inducting its next class, including Indra Nooyi, Mia Hamm, Octavia Butler, Michelle Obama, and more, this September.

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.