On this week’s 51%, we speak with Gayatri Patel of the Women’s Refugee Commission about how the U.S. can better promote gender equality in its response to humanitarian crises. Also, Dr. Sharon Ufberg speaks with Karyn Gerson of Project Kesher about the organization’s efforts to support women impacted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Guests: Gayatri Patel, vice president of external relations at the Women’s Refugee Commission; Karyn Gerson, CEO of Project Kesher; Michelle Rosales, NYS Office of General Services

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.

Follow Along

You’re listening to 51%, a WAMC production dedicated to women’s issues and experiences. Thanks for tuning in, I’m Jesse King. Last week, we highlighted the joy and empowerment that can come through traveling, and it’s a wonderful thing – but I think it’s important to remember that there’s a certain privilege inherent in traveling for pleasure, rather than by necessity.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), 82.4 million people worldwide were displaced from their homes at the end of 2020 as a result of persecution, conflict, and violence, resulting in nearly 26.4 million refugees. The struggles faced by refugees have lately been highlighted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which according to the U.N., has forced more than 2 million people – most of them women and children — to flee their homes and seek shelter in neighboring countries. That’s the estimate so far – as of this taping, Russian forces continue to push toward the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv.

Our main guest today is part of a nongovernmental organization dedicated to improving the lives of women and children refugees. Gayatri Patel is the vice president of external relations for the Women’s Refugee Commission, which also works to promote gender equality across the ways we respond to humanitarian crises. Patel notes the issue in eastern Europe right now, unfortunately, is nothing new – the Commission has been particularly monitoring the fallout in Afghanistan following the U.S. withdrawal last year.

“A lot of what we do is bring the messages of what is happening on the ground to U.S. government policymakers or to other policymakers. So when the U.S. started moving out of Afghanistan, around, unfortunately, the same time that the Taliban started taking over, and when Kabul fell, there was a real strong concern about the safety and wellbeing of women in Afghanistan – particularly those who had been active in the government, active human rights defenders,” she explains. “So part of what I was doing, along with a network of women who were similarly concerned, was really trying to make sure that particularly targeted women were brought to the attention of U.S. policymakers in Congress, with the administration, so that they could be prioritized for evacuation. There were a number of people who were helping women get out, but there are, of course, a number of women who were not able to get out. So our ongoing efforts through WRC and through some of our coalitions and networks was really to continue pushing on the U.S. government to make sure that those women who remained in Afghanistan, that their needs were met, that they were kept safe to the extent possible, and that they were prioritized for pathways out of Afghanistan if they chose to leave – or, you know, if they chose to stay in Afghanistan, that they were protected, and that their rights were protected.”

What issues do women and children refugees particularly face, compared to men?

That’s a really good question, and one that unfortunately doesn’t get asked enough. I mean, women and girls often have really unique considerations in crises like what’s happening in Ukraine and Afghanistan and in Ethiopia, Burma, etc. The biggest concerns are really related to their health and safety. So for instance, there’s an increased risk of gender-based violence, such as rape, or intimate partner violence, or child marriage. For instance, one fact that really strikes me is that, according to the UN, an estimated 70 percent of women experience some form of gender-based violence during an emergency, which is huge, huge if you think about it. Women and girls also have unique health-related concerns during an emergency: they need access to contraception, they need maternal health care, and other sexual and reproductive health care. They have nutritional needs that are unique and different. You know, that’s something that we’re right now, for instance, in Ukraine, really grappling with. According, again, to the UN Population Fund, 265,000 women were pregnant in Ukraine at the beginning of this current conflict, and they’re estimating another 80,000, will give birth in the coming three months. And I think with the enormity of the situation, it’s very easy to lose sight of the fact that these women still need health care – they’re going to give birth. And so, you know, we need to make sure that there are services there that are available for them. Nutrition right now in Afghanistan – over half of Afghan children under five years old are acutely malnourished, and they’re expecting 10 maternal deaths a day. These are all issues that are unique to women and girls and children in these crises.

And I think one thing that’s also very easy to lose sight of is that women and girls in humanitarian settings are diverse, and they experience crises differently. So, for example, women with disabilities face higher rates of gender-based violence. But because of negative or hostile attitudes, or inaccessible buildings or lack of information, they often don’t get the critical care that they need. So making sure that not only are their humanitarian responses tailored to the unique needs of women and girls, but that those responses also include age, gender, other diversity factors, such as disability or being in part of an ethnic minority – those are also really critical to keep in mind.

There’s so many things that are involved here, at stake here. And it’s really important to note that despite all of this, women and girls are largely excluded from decision making and leadership when it comes to defining their needs and the responses that will help them. And of course, this really creates gaps in responding effectively, but also really discounts that women are often on the frontlines of humanitarian response. They’re often the ones who are providing the medical care, or supporting their community members, are building shelters, or are cooking the food and feeding people. And so it’s so important to have them be part of the humanitarian response and part of that decision making – but they’re often left out. And so that’s a bigger picture thing that we really need to address as a humanitarian community.

That actually does go into one of my next questions. How can we better amplify the needs of women refugees, who are the ones facing these issues, and ensure that women are in the room for major decision making and planning?

Yeah, it’s so simple and basic, but just recognizing [that] they want to be heard. You know, in Afghanistan, a lot of what we have done – we meaning the United States has done – in the past 20 years is build institutions and build these structures [where] African women and girls are able to go to school, are able to be part of the political structures, are able to be business leaders. They had a voice. And now we are in a stage where, you know, they need humanitarian assistance, and we’re not listening to them. So we have to make it a priority to ourselves, listen to them, and make sure that they have opportunities to be heard. So, for instance, whenever there’s a peace building negotiation, women should absolutely be at the table. And it’s the responsibility of the U.S. government, other governments, other donors and actors who are in the room, to bring them in and make sure that they’re there, and that they’re heard.

I think we also need to make sure that resources are available. I don’t know if you heard recently about this announcement of the U.S. government requesting $2.6 billion for gender equality, and I just want to say, this is fantastic. This is the kind of commitment of resources that we need. It’s historic, and certainly reflects why advocacy is so important, because we’ve been pushing for years for that kind of strong commitment to gender equality. That’s the kind of commitment and show of political will that we need when it comes to really helping make a difference on the ground.

I was gonna ask, how do you feel the U.S. ranks in its response to humanitarian crises? I think you’ve touched on a couple ways already in which we can improve. But are there ways that you think we get it right? Or are there ways that you think we’ve still got a long way to go?

I think there are a lot of great things that the U.S. government does in humanitarian crises. I mean, the U.S. is the most generous humanitarian donor that’s out there. I think that humanitarian assistance, and that leadership role that the U.S. plays, really needs to reflect some of these gender concerns – and in some ways they do. I mean, there’s specific programming to address gender-based violence and emergencies, there’s support for organizations that provide sexual and reproductive health care and emergencies from the U.S., there’s support for building the capacity of humanitarian responders to see gender concerns as they’re designing humanitarian responses. And so I think all of those things are good, and need to be built on – because it’s a practical function, but it’s also a leadership function. The U.S. plays a really critical role in bringing others on board with this idea that humanitarian response needs to have a strong gender lens to it.

Lastly, is there anything that the commission is particularly looking at right now, when it comes to the war in Ukraine?

Yes, we’re really concerned about some of the protection concerns, in particular. Women and girls are, largely, they’re the ones who are coming across the borders into neighboring countries. A lot of unaccompanied children are in that mix as well. And so really, we’re looking hard to make sure that as they get to safety in those neighboring countries, [that] they have the resources, that they have the protection that they need from gender-based violence, human trafficking, etc, that the unaccompanied children have the child protection services that they need, so that they’re not abused, exploited, etc. And a lot of what we’ve seen is that organizations who are on the ground responding to the humanitarian crisis are really looking at things like cash assistance, which is something that the WRC has really kind of built an evidence base around. Not just cash for meeting immediate needs, but cash as a means of protecting against gender-based violence, or a means of being able to leave abusive relationships, or being able to meet one’s own needs rather than being dependent on others to do so in a way that could be exploited. So those are some of the things that we’re looking at. We’re also really keenly concerned about the maternal health, and the sexual and reproductive health in general of women and girls who are leaving Ukraine. Like I mentioned before, there’s the need for maternal health care, but also the need for contraception, and dignity kits, and hygiene, including menstrual hygiene management and commodities like that. So these are all pieces that we’re trying to bring together and work with advocates on the hill and with the administration and with partners who are on the ground, to make sure are really part of the mix.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. That was all the questions that I had for you, but is there anything that I’m missing that you’d like me to know, or that you’d like our listeners to know?

I think just one last point that I’d leave you with. There’s so much needed emphasis on Ukraine, and so much needed emphasis on Afghanistan – but let’s please not forget the women and girls and other vulnerable and marginalized groups that are in humanitarian crises around the world. I believe we’ve largely lost sight of what’s happening in Ethiopia or in Myanmar, or the Democratic Republic of Congo, or Burkina Faso. There’s so many places where there is a humanitarian situation still going on. And the women and girls in those situations deserve our attention and our support.

That was Gayatri Patel, vice president of external relations for the Women’s Refugee Commission. You can learn more about the Commission and its work at womensrefugeecommission.org.

Now, the war in Ukraine has prompted many in the U.S. to look into how they can personally aid Ukrainians from afar. If you’re among them, it’s important to know the best ways to go about it, and our next guest can certainly speak to that. Karyn Gerson is the CEO of Project Kesher, a network of Jewish women leaders and roughly 200 nonprofits working to empower women and promote tolerance in countries including Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, and Russia. From the project’s offices in New York, Gerson has been trying to connect with her contacts across Europe in order to provide direct aid to women on the ground in Ukraine. It’s an ongoing situation that is constantly changing, but she recently provided an update to Dr. Sharon Ufberg, co-founder of the California-based personal development and wellness company, Borrowed Wisdom, for her 51% segment “Force of Nature.”

“On a daily basis, I talk to women in the region. And frankly, every conversation starts in tears. I don’t think that anyone really could have imagined how quickly and how aggressively this war would progress. And as a result, I think most people are really just in shock,” says Gerson.

Ufberg: What are the women telling you? Are most of them wanting to flee? Are most of them wanting to stay? How are they responding?

Gerson: I think if you had asked me a few years ago, because my specialty is the Jewish community, I think that I would have expected many people just to leave the country. But now there’s a much higher sense of patriotism than I’ve heard in the past. I think the last few revolutions in the country have really given Ukrainians a sense of ownership of their country, and a sense that the possibility of becoming more free and more European was really not too far out of their grasp. So increasingly, I’m hearing from women that they would really like to stay in their country. But everything depends on what’s going on. One of my top leaders had said that she would not be leaving her town or her house until the tank rolled up to the door. Well, this week it did. And so now she’s on the road, and she’s moving west. And so I think this is a constant shifting situation.

Ufberg: And how is Project Kesher responding to this ever-changing situation? What do you see? What are you doing?

Gerson: So Project Kesher is in every oblast, every state across Ukraine. And so normally, we would really be very active and volunteer in each of these areas – but right now, everybody is in motion, and everybody is shifting. And so as I was laying out, we talk to each woman, and we try to find out their plan of action. Are they saying, are they moving? Are they leaving the country? Or are they potentially going to Israel? And after that, we are trying to get small grants into their hands. This is a very poor country. Women are unlikely to have a bank account, a credit card. If they have a debit card right now, it’s not that easy to get money on the debit card. And so we’re trying very hard to teach women how to download apps onto their phone, and to get money for them through things like Pay Pal. The goal is to basically give them enough peace of mind to make the journey wherever they need to go to have some shelter, to get some food, and then to really make sure we pass them off safely to the next organization that will either help them in western Ukraine or help them as they begin their journey to be a refugee. Our plans are to stay primarily focused on the women in Ukraine, where we have the most ability to have an impact. We’re going to leave the refugee work to organizations like HIAS and the GDC and several others. And then because, again, we do work in the Jewish community, we will be working with a group in Israel to help on the intake of the new refugees there.

Ufberg: Are you finding that these 200 women’s groups are rallying around helping one another? Are people feeling isolated, or is the Project Kesher community responding there and helping one another?

Gerson: Well, you really can’t talk about groups at this time at all. Everybody is really trying to make the best decision for their family. I’m really working right now mostly with individual women, many of whom I’ve known for more than 20 years. And I can picture each one of them. And some of the things that we’re doing, for instance, is we had one bank account in Ukraine – the city where that was located is getting increasingly under a military assault. So on one given day, we opened eight new bank accounts, you know, seated each one with $10, to see if the wire transfers would go through. And then the next day had women go into the bank to see if they could get the money out. And so now we have bank accounts across the country that today are working. Whether they will work tomorrow or the week after, we don’t know. But we’re trying to stay incredibly flexible, so that as we see things unfold and the needs start to present themselves, we are in a position to use the money that has been entrusted to us to be as flexible and responsible to the women as possible.

In the first few days, I thought, “Well, what can we send?” And what I’ve learned from the wonderful Ruth Messenger, who was the head of American Jewish World Service, one of the leading relief organizations in the world, is don’t send anything. And the reason is that the roads in that region are congested, the ability to unpack and distribute materials is very, very complicated, and really almost impossible to achieve. And also these economies in like Moldova, and Romania – to the extent we send resources, we send money to the expert organizations on the ground, they will be able to make purchases that will also stimulate those economies, because these are countries that are taking in refugees. And by saying to them that we will make these purchases through their countries, we’re saying that we really appreciate that you’ve taken all these refugees in. One of the other things Ruth has taught me in the last few days is that if we send too much product into a country, the country will start to put taxes tariffs in place, and start to make it expensive for the nonprofits to accept these overseas packages. So I would encourage everybody who is trying to be really caring and compassionate, that if they can send money – do not send things. I would also say [we need] to realize this is going to be a long haul, that we are not going to resolve this issue quickly. These are going to be refugees for quite a long time, and Europe is going to have a heck of a time absorbing this number of people. And then there are going to be people, we hope, that when Ukraine is secured and peaceful, will choose to return home, and then the rebuilding will be a very major expense as well. So if this is a region of the world and a people you care about, be prepared to be involved in this process for many years to come.

Ufberg: Thank you. Karyn, can you give us some information how listeners could find you to learn more?

Gerson: So Project Kesher can be found on the Internet at www.projectkesher.org. I’m reticent to talk about too many organizations – there’s quite a few great ones, but I’ll just mention one, and that would be Afya. They are doing medical supply transports to the region. And if you are interested in helping to get medical supplies over, they have expert experience doing so. Again, if you just start packaging up things, it’s not going to get where it needs to be. But if you work with an expert in global relief and crisis situations, then you know your monies are going to be well spent.

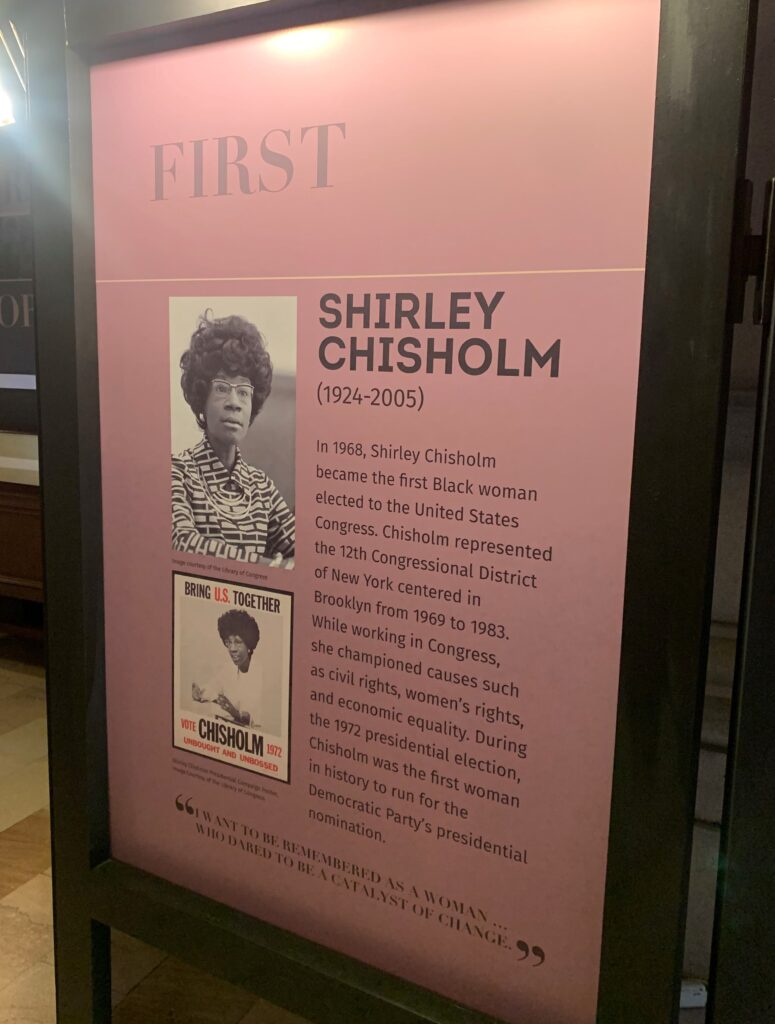

We’re going to change gears somewhat now to recognize Women’s History Month. Cities, businesses, and museums across the country are celebrating women in a myriad of ways, and throughout the month of March, I’d like to take some time to learn about the prominent women in our past and present. We’ll start with the annual Women’s History Month exhibit on view at the New York State Capitol. You can find it in the governor’s reception room, or “war room,” on the second floor. The war room has this intricate ceiling mural depicting some of the state’s heroes amid a slew of battle scenes, both real and mythical, but for the rest of this month, it’s women’s faces and stories that take front and center. This year’s “First and Foremost” exhibit features 20 New York women who either made history by being the “first” to break down certain barriers for women, or who rose to prominence as the foremost expert in their chosen field.

“It’s really hard to pare it down, honestly,” says Michelle Rosales, a spokesperson for the state Office of General Services, which assembled the exhibit. “We have so many great historic women, and doing the research, we always end up having some for next year or the following year, you know?”

As you check out the various panels you’ll catch some familiar faces – Governor Kathy Hochul, State Attorney General Letitia James, the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sojourner Truth – but you’ll likely notice some new names as well.

“Here we have Dr. Helen Rodriguez Trias,” Rosales motions. “She lived and worked in both New York and Puerto Rico. She worked a pediatrician, and while she was doing that, she became aware of ways social and economic equality affected one’s access to healthcare. So she spent the rest of her career educating and advocating for healthcare accessibility and women’s reproductive rights.”

Rosales says one of her favorite women featured is Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to the United States Congress, who represented New York’s 12th District in Brooklyn from 1969 to 1983. Chisholm was born to immigrant parents on November 30, 1924, and she initially sought a career as a nursery teacher, getting her masters in early childhood education from Columbia University. But she was also a vocal activist, and became the second Black representative in the New York Legislature – behind Edward A. Johnson – before ultimately running for Congress. As a Congresswoman, Chisholm helped expand the food stamp program, advocated for the Equal Rights Amendment, and spoke out against the Vietnam War. In 1972, she took things a step further by running for president, becoming the first woman and African American to seek the Democratic Party nomination for the role.

“And she has a quote that I like, personally: ‘If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring in a folding chair,'” adds Rosales. “I just love that, because it’s powerful, and it’s taking charge and making changes.”

At the exhibit, you’ll find some campaign buttons from Chisholm’s presidential run, as well as some White House invitations from Eleanor Roosevelt and a record by Native American musician Joanne Shenandoah, who died last fall at the age of 64.

“She’s a Grammy Award-winning artist born in Syracuse, New York, and a member of the Wolf Clan Oneida Nation. She used her heritage for her activism, so it went beyond music — she was on the task force on American and Alaskan Native Children Exposed to Violence for the U.S. Department of Justice during President Obama’s administration,” Rosales notes. “I want people to walk away from this exhibit feeling empowered, inspired. I have three daughters of my own, and not just for the women looking at this exhibit, but also for anyone coming here — I want them to feel like you can make change. You can look at the history and what these people have done in their various fields of study, and know that it’s OK to ask questions. It’s OK to push boundaries and call for equality and just make it fair.”

The First & Foremost exhibit is open to the public through March, weekdays from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., in the governor’s reception room in the New York State Capitol. If that’s too much of a trek for you, no worries, you can also catch it online.

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. It’s produced by Jesse King. Our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.