On this week’s 51%, we hit the streets. We stop by a rally for the Women’s March in Albany, New York. And we also speak with author and researcher Heather McKee Hurwitz about what we can learn from the Occupy Wall Street movement, 10 years later.

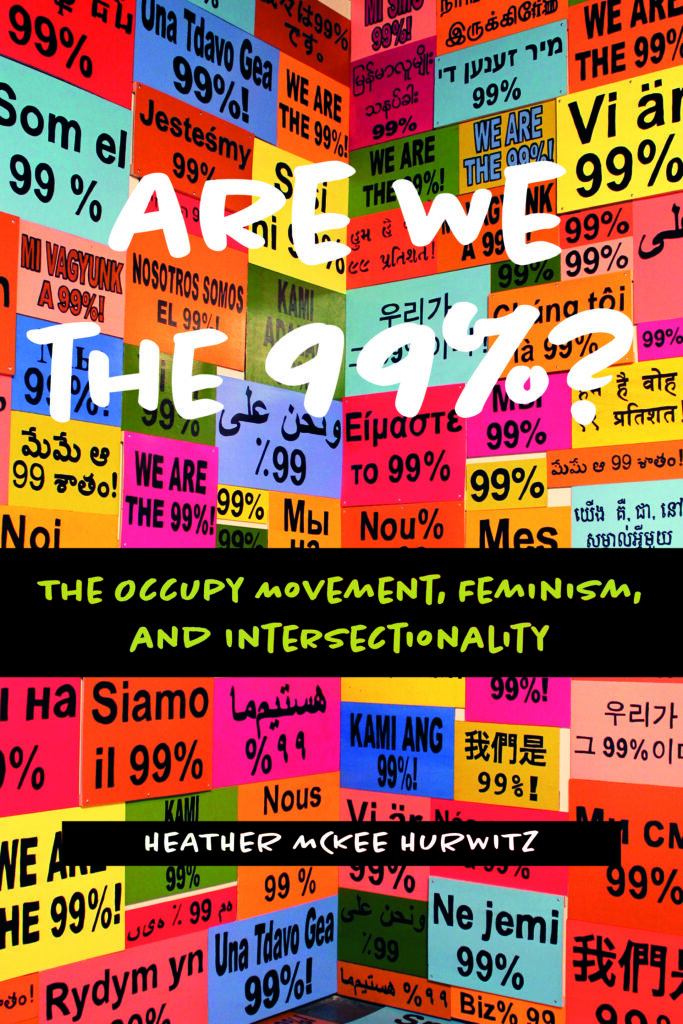

Guests: Heather McKee Hurwitz, author of Are We the 99%? The Occupy Movement, Feminism, and Intersectionality

51% is a national production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio. Our producer is Jesse King, our executive producer is Dr. Alan Chartock, and our theme is “Lolita” by the Albany-based artist Girl Blue.

Follow Along

You’re listening to 51%, a WAMC production dedicated to women’s issues and perspectives. Thanks for tuning in, I’m Jesse King. We’re talking women in activism today – starting with the Women’s March.

On October 2, thousands of protesters marched in cities across the U.S. for the fifth official Women’s March. The movement, prompted in opposition to the election of former President Donald Trump, has never quite seen the turnout it first received in 2017, when hundreds of thousands of women marched in Washington D.C., and an estimated millions more followed suit in cities across the globe. But this month’s march had added fuel in the form of the now more conservative Supreme Court and Texas Law S.B. 8. The Supreme Court is expected to take up a case that could threaten the future of Roe v. Wade by the end of the year, and in September, Texas enacted the “Texas Heartbeat Act” to restrict abortion at the six-week mark – before many women even know they are pregnant.

The combination has led to enormous outcry from aboriton providers and abortion rights activists across the country. National organizers for the Women’s March actually bumped up this year’s event from its usual winter/spring slot specifically to “rally for abortion justice.” In Albany, New York, a woman’s right to an aboriton is much more protected by state law, but a few hundred people still rallied outside the State Capitol in support of Upper Hudson Planned Parenthood. Chelly Hegan is the center’s president and CEO.

“We all deserve to be seen as full, human members of our society. We deserve to make decisions about our own destinies. We deserve to be free from violence, from oppression, from shame, from stigma. We deserve to live the dignified lives in front of us,” says Hegan. “Today we stand together for abortion justice, but we will come together again for justice in all its forms. Together we are an unstoppable force. I will stand with you, I will hear you, I will fight with you, and I will win with you.”

The rally outside the State Capitol was perhaps a lot less tense than it may have been in D.C. or Texas, with very few counterprotesters in attendance and almost a party-like atmosphere within the crowd. Making my way through the crowd, I found many protesters lounging on the Capitol lawn, dancing with friends, or taking selfies in front of the Capitol building – plus many, many signs, ranging from the typical “I stand with Planned Parenthood,” and “My body, my choice” to more…creative pieces that I can’t read over the air.

Alana Yannick, Molly Merola and Margo Springer all came with friends, both for the community and the cause.

“Without basic healthcare of any kind – which this is basic healthcare – you can’t have a functioning society,” says Yannick.

Her friend, Merola, nods. “I came here because I think that every one deserves the right to their body, and I think the Texas law is absolutely disgusting. It just really bothered me when I heard it, and how much Albany does for women is just amazing to me. So every time there’s an event, Alana and I are out here. Women just deserve the right to choose no matter what age they are. I just love women and think women deserve everything that a man has, honestly.”

“For me, as an older person, it’s so great to see young people here. My friends are here with their children, their grandchildren, all ages, race, men and women,” says Springer. “And I think we’re very happy that we have a woman governor who is so prominent in her support for reproductive rights. But we need to be here to support the people in Texas and across the nation.”

Ultimately, the day itself was short and sweet. Where the Supreme Court will stand on abortion later this year remains to be seen. On October 6, a federal judge temporarily blocked enforcement of Texas Law S.B. 8, following an emergency request for a preliminary injunction from the Justice Department. But the Women’s March has had a few bumps in the road on a national level. While it’s had diverse leadership, the movement as a whole has been criticized as a space for primarily white, cis-gendered women, and in 2019, three of its founding members stepped down amid allegations of anti-Semitism.

Many of the protesters at Albany’s event said they feel the movement is getting better on that front. Upper Hudson Planned Parenthood’s Chelly Hegan particularly noted the diversity of the crowd, and said she specifically planned a rally, rather than a march, to make the event more accessible for attendees. But the conversations happening within the Women’s March are not uncommon for large protest movements.

Heather McKee Hurwitz is a sociology and gender studies researcher based in Cleveland, Ohio who has long focused on the Occupy Wall Street Movement, which marked its 10th anniversary starting in September. This time in 2011, thousands of protesters took to the streets of Manhattan, with many camping out in Zuccotti Park, to protest income inequality across the U.S. The protests in New York City were accompanied by similar movements in cities nationwide, and McKee Hurwitz says it really was part of a worldwide conversation about income inequality following the start of the Great Recession in 2007. Despite that – and despite the movement’s slogan, “We are the 99%” – McKee Hurwitz says not all of Occupy’s attendees felt equally represented by the movement as a whole.

She spent years speaking with more than 100 protesters in various organizations and encampments tied to the Occupy movement, and in her new book with Temple University Press, titled Are We the 99%?: The Occupy Movement, Feminism, and Intersectionality, she looks back on the movement’s legacy, and what activists today can learn from the way it all played out.

You talk a lot in the book about “collective identity” and “oppositional collective identities.” Could you go into what that is? And what were some of the identities at play in the Occupy movement?

Collective identity is a fancy word meaning “the feeling of being part of a group, feeling like you’re a ‘we,’ or ‘us,’ or ‘us together.'” And the primary collective identity for the movement was, “We are the 99%.” It was the idea that anyone except for that 1 percent most wealthy have a reason to feel like we’re part of a group, and we have a reason to be together. At the same time, especially the women who I spoke with, said, “Are we the 99 percent? Are we really part of this 99 percent? Are our particular issues as women being recognized in this movement?” And also, women of color, and racial justice activists of a variety of genders, people of minority sexualities, also really questioned, “Am I part of this collective identity of the 99 percent?” And as a result, they formed their own groups, these oppositional identities – so kind of subgroups. A place where they could feel more like they belonged, like they were more of the “we” of a group that was a name like “Women Occupying Wall Street.” A number of the women I spoke with said, “You know, I can really see myself as a part of this group, I feel a part of this collective. And we’re gonna use this separate subgroup to kind of push against that 99 percent identity, and try to make more of a space for women to be included by having this kind of separate group.”

And so I found a lot of that happening within the movement. In fact, it was phenomena that I credit with part of the kind of faltering of the movement. There were so many of these splinters and separate groups [that it] started to fray away at that overarching 99 percent identity.

You go into detail in your book about how women and minorities felt that either they weren’t considered part of the 99 percent, or weren’t protected as part of the group. At the time, there were reports of sexual harassment or sexual assault in the encampments. There was even some opposition to the word “occupy” in Occupy Wall Street, with some indigenous people noting that word has ties to colonization, so you had groups like “Decolonize Wall Street” popping up. Tell me a little more about the various arguments being made by these subgroups.

Absolutely. These subgroups felt that the framing of inequality as just economic-based, class-based, about somebody’s income or job – was really not enough. The Great Recession, the economic downturn of little more than 10 years ago, impacted women and people of color more severely than other groups. I mean, everyone really was impacted, so many people lost their homes and their jobs – but there were a disproportionate number of older, African American women who had been kind tricked into these mortgages, and were left unable to pay and were being evicted. And these groups came at this problem and came at this movement with an intersectional lens. Intersectionality is this idea that Kimberly Crenshaw, a professor and lawyer, developed to help us to understand that inequality is not just one dimensional. It’s not just about class, but [also] about those experiences that people had as being women: in their sexuality, their particular racial identities, and the kinds of inequalities or lack of privileges that perhaps came along with some of those more underprivileged positions in our society. It really shaped how activists saw the problems of the day and were trying to address them. And these subgroups were so focused on having that more intersectional analysis.

Let’s talk a little bit about some of those specific groups, then. What are some examples of ways that you saw them contributing to the movement, but in their own way.

So, when women felt that they weren’t being thought of as the leaders, or someone who could take a great responsibility for the movement, I found that women’s groups broke off and did some of their own things, and drew on their femininity to really do unique kinds of tactics. And one of them that comes to mind is protests in front of Bank of America, where women brought bras, they kind of flung the bras at the bank, to say, “Bust up big banks!” So using that play on words, bringing the bras to kind of call attention to Bank of America and say, “This bank has gotten way too big.” That idea of “too big to fail,” well, they felt, we really need to transfer our money into smaller banks. And they called attention to it by wearing pink and bringing pink bras and trying to get more women involved. So that’s one way that women kind of used their femininity in a unique way.

There was a great group called “The Safer Spaces.” They were staunch supporters of the Occupy movement, and they felt that there was a need for a kind of community pledge that this was not just going to be any old activist space, but a space where people could be striving to end things like racism and sexism. People could take into account that, for women to camp overnight, in an urban environment, with a lot of people that they did not know, they need some extra security, especially if, let’s say, that they may be bringing children to the event. They helped to create these separate spaces. So not only the agreement, but also tents and designated areas that women could camp and sleep together. And that became a great way to encourage more women to join into the protest.

As far as the main movement was concerned, how did they view these subgroups? Did they see them as contributing to the overall movement and expanding the message, or as diluting the message?

Contributing but not part of that main movement. There was a greater appreciation for the vast diversity of these different subgroups, be it a Spanish-speaking newspaper that developed within the movement, to queering OWS, which was a group specifically for LGBTQ+ persons. And these groups were so important, because it was a space where more non-traditional leaders could really have a space and a voice and put forward important issues. And that was appreciated by the movement overall, but not woven into that central core idea of what it meant to be Occupy, what it meant to be “the 99%.” And that’s where I think the movement kind of faltered. If groups in the future see this kind of splintering happening, it’s not just a moment to appreciate it, but to really stand back and kind of re-examine that movement and say, you know, “Why are people feeling they can really be themselves in these separate groups, but not in the main group? Maybe we need to stop, we need to retool things, we need to do something differently.”

How was the main movement structured? Was there any kind of leader that could have stepped in and said, “Hey, let’s re examine this.”?

There was not a central leadership hub. Part of the beauty of it was anyone could come down and take responsibility and develop a creative space or movement or tactic or march. And there’s something really great about that. But as the movement got to be so big, and as different elements started popping off within the movement, there wasn’t really a central group to bring it back to a core message or to say, you know, “This is a great protest happening, we like this message, it’s on point with the movement. But maybe the video about the ‘Hot Chicks of Occupy Wall Street’ is not really on the point. It’s not really being inclusive. It’s not really the message we need.” Unfortunately, because the structure was just so voluntary, and so kind of rotating, there wasn’t that check on the movement.

If there were, is there a way that you think that they could have had that conversation in a productive way? Because it is such a large group. I mean, we’re talking, “We are the 99%.” That’s the majority of the world’s population, and we have trouble navigating these conversations on a day-to-day basis, let alone when you’re trying to determine the overall demands and messaging of a movement.

Oh, it’s so tough, and it was so really utopian. As much as I critique the movement, I celebrate it as well. I celebrate it also, in part, by critiquing it. Because they had this vision, this big tent movement, a force of progressive politics, saying “How could I involve everyone, and let’s make some really substantial change?” There’s something so powerful and exciting about that moment, and it got thousands and thousands of people into the streets together. Could there be a way to kind of orchestrate more, or have more leaders? You know, they tried, they really tried, and I feel like there’s a lot to learn from the movement that groups in the future could [learn]. Potentially, if there were a central body to go back to, if there were those moments of recognizing the messages or framings that were not intersectional. If there were leadership trainings that were consistent and understood the great under representation of women in leadership, right, and acknowledged it head on – that the majority of activists, leaders and political leaders who were interviewed in the newspaper are not women, and that’s a problem. I think there are some steps that could be taken to make even a large scale, big tent movement more inclusive.

And so what remains of the Occupy movement today? Do you think anything like it could happen again?

I do think that something like it could happen again. I’m inspired, really, by the trajectory that started from the Occupy movement. So of course, there’s been feminist activists and racial justice activists and anti-police-brutality activists long before the Occupy movement. But the Occupy movement really got people into the streets 10 years ago, and we’ve seen so much activity in the areas of protests since then. Many of the people who met at the Occupy encampments formed friendship networks, they formed various groups that kind of spun off of Occupy. People floated into the Black Lives Matter movement. Many of the people who were active in Occupy joined up with Bernie Sanders, who really has the same message. I mean, he jumped on the heels of the Occupy movement and used that idea of the 99 percent versus the 1 percent. You know, I don’t think we would have the Bernie moments that we had without Occupy really starting to popularize that idea about inequality. And so there have been a lot of groups that continued and transformed. Some of them kept the Occupy name, like “Occupy The Farm,” which was based in California. Some of them shifted into other configurations, like to support Bernie Sanders, and I’m sure that a number of women who met at the marches in Occupy floated into the anti-Trump organizing and, you know, were sparked by that initial Occupy moment, but joined the Women’s March and other areas. I mean, that’s, that’s in part, my story. I’ve just kind of stayed active since the Occupy movement. And I think it really helped to get going this incredible period of activism that we’ve seen over the last 10 years.

What was your own personal experience as being a part of this movement, and in movements going forward?

So I really wore three hats in this movement. I was a participant, I was a researcher, so I would go home and just dig into all of my notes and kind of stand back and reflect on the movements. And at the same time, I was a feminist. I came to the movement thinking about issues, about inequalities and diversity and inclusivity in the movement, kind of bringing that feminist lens and really wanting to talk with a lot of the women activists and hear their stories and record them, because many women were not interviewed in the mainstream media or heard within the movement – and yet, they played a really important role. And so I’ve spent the last years since then, both writing the book, speaking around the country about the book, and continuing to do activism myself. And just trying to use all of the skills that I can as both an activist and researcher to address inequalities. And that’s my continuing work. Now I’m working a little bit more in the health sphere, on ending health disparities. But I see it as a continuum of addressing sexism and racism in a range of different areas of life. And I definitely think about my colleagues from Occupy and the wonderful experiences I had, and the challenging experiences, I think, still shaped me personally.

You’ve been mentioning some of the lessons we can take from the Occupy movement. Is there anything else you’d like activists or aspiring activists to know?

Well, I think it’s important that activists today, or anyone who’s just come into political life, be it through protesting for or against the Trump administration, or Bernie Sanders, to know where some of this activism has come from. The initial Occupy moment was an important moving of people into the streets and getting a vision for a different kind of a world. There’s a lot to learn from the Occupy movement. I have actually created an archive of documents from the movement, more than 400 documents that people can revisit, so that when future activists encounter things like, well, “Should we have a voluntary leadership structure?” or, “There’s a number of disgruntled women in the group here who don’t feel really safe in our protest camp. What should we do about it?” Well, we could look to the Occupy movement, and what happened in those experiences, and not just do the same thing, again.

Many of your listeners as they’re hearing this, they may be thinking of women who were active in the Civil Rights movement, or the New Left – these issues of women being thought of as second-class activists, or not getting the leadership roles, or feeling like they were objectified as part of their activism. Unfortunately, these are not really new issues. In the Occupy movement, people dealt with it more quickly than activists of, let’s say, 30 or 40 years ago, but these issues are still there. So we, I think, should be a lot more conscious that that is a dynamic, even within progressive movements. And we need to be really conscious about ending gender inequalities in even our progressive spaces.