This week on 51%, we bring you the first part of a two-part series on rape and sexual abuse. Host Jackie Orchard visits the crime victim services unit of a hospital to learn about what’s involved in a forensic rape exam. And a counselor tells us what recovery looks like after an abuse.

A warning that today’s program contains details and subject matter than may not be appropriate for all listeners. We’re going to be discussing sexual assault for the next half hour.

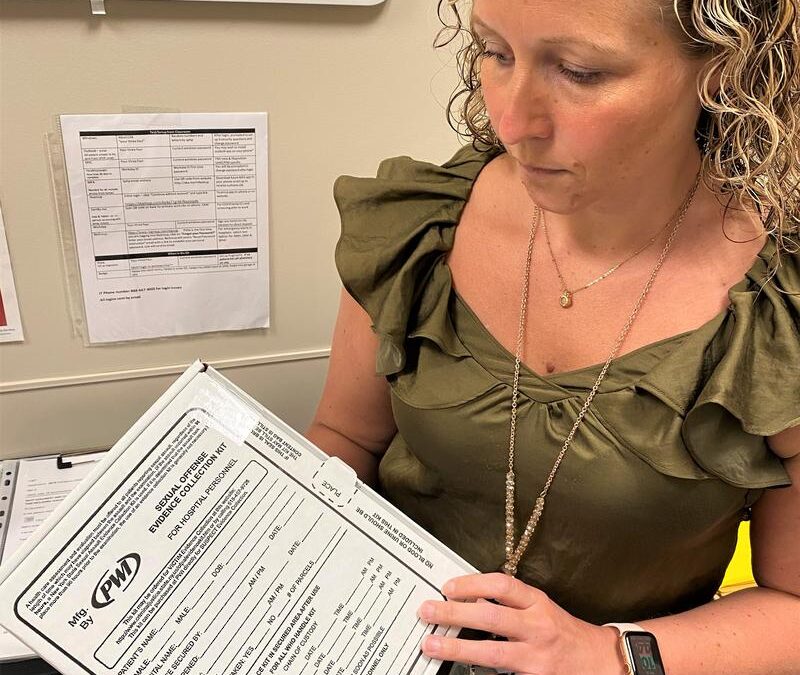

Grace Coons is the supervisor of the forensic examiner program in the Crime Victim Services Unit at St. Peter’s Health Partners. Standing in the emergency department at Samaritan Hospital in Troy, New York, she opens a rape kit to show me the envelopes and instructions inside.

I have to say, imagining going through the steps as if I were the patient – a genital swab, photos of bruising, DNA samples, and recounting the story for the advocate or the nurse to hear – it seems overwhelming. But Coons has a very confident air about her. Like a mom you would call late at night if you were in trouble – and she would swoop in and make it all OK.

For good reason. Coons has been an examiner for about four years and has seen hundreds of patients for varying types of abuse. Coons is a nurse practitioner and manages about 38 per diem nurses. They take varying shifts to administer forensic examinations for victims of rape and abuse. And the amount of abuse patients they see is… upsetting.

“This year, we’re actually averaging approximately 40 per month,” Coons said. “Last year total, our program saw 280 patients. So far, at the close of May, our program was at 215. So we’re almost double the volume of last year, just with this year.”

Coons says it’s nearly impossible to identify trends of who gets raped or abused.

“There is no set demographic,” Coons said. “It can happen to male, female, transgender, all ages, we see basically from infant all the way to elderly folks in their 80s. So there’s a very wide range of our patient population. So it’s not a specific demographic, or race or anything like that.”

Coons says they see patients for all types of abuse, not just sexual. Usually children come in because of a domestic violence incident.

“We could see them for a physical assault, we could also see them for a sexual assault exam,” Coons said. “So it might be something that is either known and so we are collecting evidence for a known sexual assault, or something that is presumed or that there’s a hunch, you know, that something just doesn’t seem right. Maybe somebody heard something or, you know, their genitalia has suspicious redness, you know, when an unusual bruise… or a child just not acting right and the parent or guardian wants the child checked out. Sometimes we can also see pediatric patients because of CPS involvement and CPS is requesting the exam.

Coons says her department is trying to set standards for domestic violence patients across the state, hoping New York will develop a set evidence collection kit for domestic violence examinations.

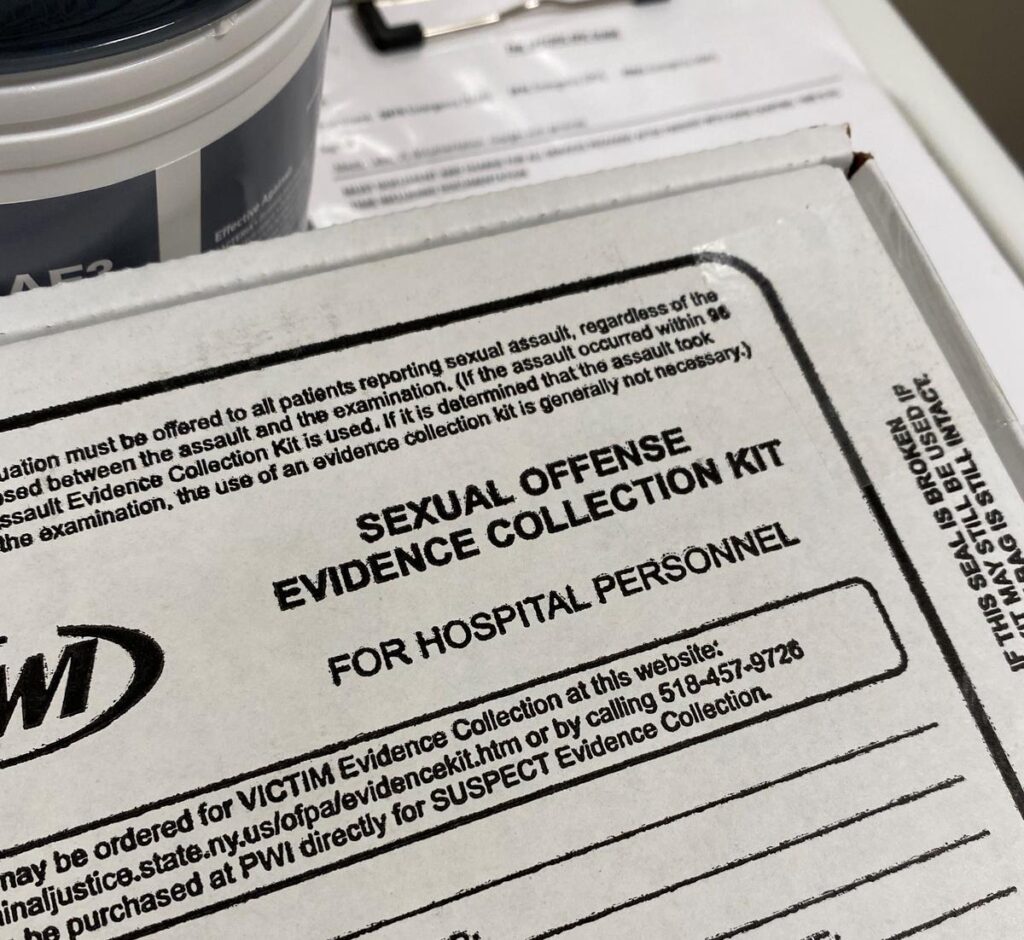

“In New York State, there is a set kit which would be used for any sexual assault patient throughout the state,” Coons said. “So if you were seeing here or Buffalo, you know, anywhere from corner to corner of the state, then you would have the exact same evidence kit collected for you. But those standards don’t exist for domestic violence patients. There’s also not a reimbursement process for domestic violence patients. So that would have to go through that individual’s insurance at this point, whereas someone who were sexually assaulted, can have their services, free of charge in your state would pay for that. So we’re looking to kind of set some standards and best practice protocols for New York State.”

Coons says Crime Victim Services also sees patients who are victims of general physical assault, human trafficking, abuse, neglect, and elder abuse. But most patients are sexual assault and domestic violence victims. She says when she is paged for an abuse victim, she never knows what she’s walking into.

“Some patients who are physically abused may show signs and symptoms like bruises, scratches, things like that, and others may not,” Coons said. “The mechanism of injury and the amount of force, how long it lasted for is no correlation to what type of injuries you would see on an individual. So that would, you know, cover everything from punching, hitting, kicking, hair pulling down to sexual assault. So, you know, presence of injury in the anal-genital region is not necessarily an indicator for there being a sexual assault. So that does not prove whether or not there was a sexual assault.”

Coons says to prove sexual assault, you need DNA. That’s where the “rape exam kits” come in.

“When we come in to see a patient, first thing, we want to make sure that the patient is medically stable,” Coons said. “So that’s our number one, before we’re doing anything, making sure that their medical needs are addressed. If there is anything that let’s say the patient was strangled. They’ll need some imaging done to make sure that there is no internal injuries done that we can’t see with the naked eye that could potentially be life threatening. If the patient is pregnant, we want to evaluate that baby to make sure that baby’s OK. So medical stabilization first, then we would go into certainly a safety plan and then going into what their options are for evidence collection.”

Coons says evidence collection is always the third priority.

“The patient would have the option to do anything that they wanted to do, the exam is always patient-driven,” Coons said. “They’re not locked into collecting evidence, but it’s totally up to them, we’ll educate them and let them know that what the benefit of collecting DNA evidence is, if they would like to proceed with doing that evidence collection kit looking for DNA, we’ll go ahead and do that. They can consent to some of the kit and not all of the kit, they may also want to do blood and urine samples to see if there may be any drugs in their system, let’s say, you know, the common term would be roofie, let’s say someone had something put in their drink. So they would have the option to do that. They can, you know, consent to some of it or all of it, if they have some injuries that we see in our exam, we could also document those injuries medically. You know, write on paper, how big the measurements, what it looks like, the color, all descriptions of that, but they would also be able to choose if they wanted to have their injuries photographed. Any photographs would be used for evidence purposes only and held in a secured location. So they would also have the decision to make if we wanted to keep their evidence and store it here while they decide if they want to report to law enforcement have it released. Or we could release it same day. Presently New York State law has evidence being held for up to 20 years while someone would choose whether or not they wanted their evidence processed for DNA. So, you know, someone today may not want to report to law enforcement, may not want their kit tested for DNA, but maybe two, three years down the line, even 20 years, they may say, ‘Geez, you know, I’ve been really thinking about this, or I heard this person did something to somebody else. And I really think it’s time that I have my evidence tested to show that this person had done something to me as well.’ So we would have their evidence still in storage that could be processed up to 20 years later.”

Coons says it’s hard getting people in the medical community to understand the depth of compassion it takes to handle cases of abuse and assault survivors.

“Even simple medical procedures or exams can be triggering to these individuals moving forward,” Coons said. “And they may not want to express all that they have been through in the future to new providers, it can be very uncomfortable. So that is challenging, just to know that, you know, how to engage other providers in a way that they can be what we call ‘trauma informed’ and provide services in a way that are non-threatening to patients who have an abusive history.”

Coons says her job is important because often she is the first person a survivor of rape or abuse will interact with after the incident.

“That’s really what it’s all about, making that humanistic connection, and meeting them on their level,” Coons said. “You’re really connecting with these patients on potentially one of the hardest days of their life. And just being able to say, ‘OK, here’s what I can do for you. Even if you don’t want it, here’s what I can do for you. And I take no offense if you don’t want to participate.’ And, that’s just kind of what it’s all about, just showing that you’re, you know, raw with them.”

What Can I Expect From A Rape Exam?

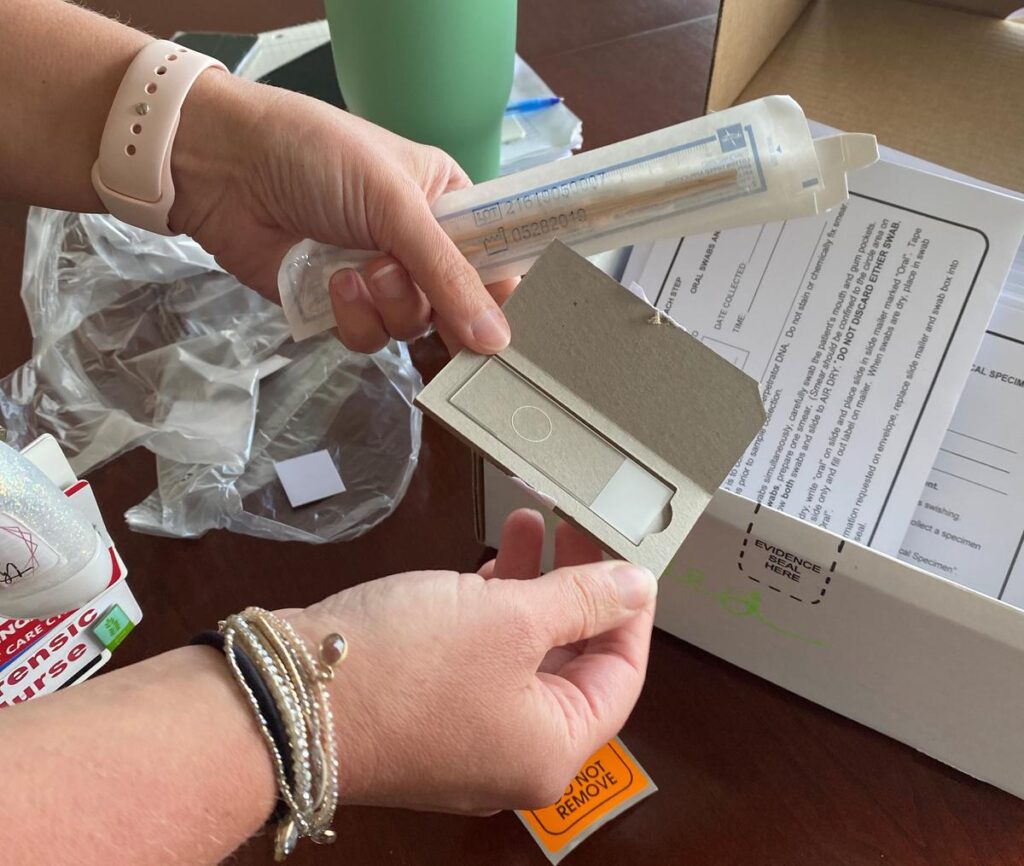

Coons lays it out for me. Literally, we went through a rape examination kit together. Here’s what you can expect if, heaven forbid, you are raped and go to the Emergency Department for help in New York state.

One. When you arrive to the emergency department, the on-call victim advocate and the forensic examiner are paged immediately and have one hour to get to the hospital. You also get special priority in triage.

“So when they are aware that you are there for a sexual assault exam, you’re basically bumped up ahead of everyone else in the waiting room and pulled back into a private room ASAP,” Coons said.

Two. You’re going to get asked a lot of questions.

“What are your allergies? How tall are you? You know, any surgeries in your lifetime? Do you take any medications,” Coons said.

Three. They’re going to ask you about the incident. And you need to tell them everything you remember.

“What are the details, what time it happened? Where were you? Do you know the individual’s name? What are their relationship to you? What parts of their body were either touched or hit or grabbed,” Coons said. “Where should I be looking — number one, for injuries and number two, for any DNA.”

Next, DNA DNA DNA. If you want your abuser or rapist convicted, they need to swab everything. And you need to tell the examiner where to look.

“What type of DNA,” Coons said. “So, would I be looking for saliva? Would I be looking for touch DNA? Should I be using a fluorescent flashlight to be looking for any bodily fluids or not? Did this happen three days ago when this patient has changed their clothes since then, so I wouldn’t need to evaluate their clothing, or did this happen two hours ago, where they were wearing the same outfit, and we can offer to submit their clothing for evidence as well.”

They’ll need to swab your mouth as a control, so they can compare foreign DNA to yours and maybe find foreign DNA in your mouth as well.

“Sometimes there’s oral contact with the other individual, whether it may have been kissing or you know, oral intercourse or forced oral intercourse,” Coons said. “Sometimes the sexual assault may have started out as consensual. And at a certain point, consent was withdrawn, and the patient was no longer participating, or you know, an active participant in whatever that encounter was. So you can get sometimes the perpetrator or perpetrators DNA from oral swabbing as well.”

You can opt to get a speculum exam, or not, and you can opt to get tested for all STDs, or not. Every step is up to you.

Caught In A Cycle

Coons says the hardest part of her job is seeing patients who have been assaulted more than once.

“That they’re kind of reliving their first assault as they’re processing a second assault,” Coons said. “So that would be one difficult… I think some would say that, you know, going to the exam itself and hearing the stories, whereas I find that to be a source of strength for the patient, that in their time of crisis, you can be there and able to help that person, I find that more empowering than difficult. Whereas, you know, someone who may have a different background or, you know, skill set may feel very uncomfortable with that scenario. But I do not find that to be a challenge.”

Coons says she sees a lot of repeat patients, who may be caught in a cycle of violence and abuse. She wants them to know that there is hope, and there are people in her department who want to help.

“Whatever happened with that very first encounter, that potentially has maybe blurred some boundaries or skewed some ways that that individual may think of things,” Coons said. “There’s so many services out there to help these individuals cope and deal with what has happened in the past, and to work through all that they have been through that, doing that and working on themselves and their feelings, and their traumas, and all. All of that all the counseling and therapy part of things is so critical and important. And that can actually help them to understand how they’re processing things, and to help them create a plan for the future.”

Where Is Your Happy Place?

One of those people waiting to help is on-site therapist Emilia Alsen, just down the hall from Coons’ office.

Alsen has around 30 clients and uses cognitive behavioral therapy, combined with talk therapy, to help people work through trauma.

“It really focuses it focuses on being able to stop and check your thoughts and kind of see if they’re accurate,” Alsen said. “And also check in with yourself about your feelings. And resourcing and grounding and relaxation is critical.”

Alsen also uses EMDR, or “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing,” therapy.

“You’re having a person focus their attention,” Alsen said. “So while the EMDR practitioner is encouraging them to bring up a target memory, the practitioner is also helping provide a stimulus, a dual attention stimulus. So either it could be eye movements that have them — you track my fingers and my fingers would track your eyes across the midpoint of your brain. So what ends up happening is by focusing your eyes, left, right, left, right, or you could do it with taps on your knees, or you can do it with sound in your ears or special equipment. And essentially what it does is that it coordinates the brain movements. So it’s going back and forth and back and forth between right and left hemisphere. And what it does, it actually expands and opens up the corpus callosum, which is essentially like the hallway between the two sides of the brains. And so when both sides of the brain is talking to each other, and then connecting in this hallway, this passage is being opened — the content that the patient is recalling — theoretically, transitions from one part of the brain where it’s stuck. And by doing by opening up that bridge, the corpus callosum can actually transition to the place where it needs to be to be stored correctly. Because that’s the problem with trauma is that when you experience a traumatic event, you are in such a state of survival, that even the thought of that event later down the line triggers that that survival instinct, even in a place where you might be safe. And that’s problematic for people who are living, you know, in a nine to five world where they’re not necessarily escaping saber toothed tigers on the, on the sidewalk, you know, could be an event, you know, that to that person was really, really struck a chord with them. And it can be really difficult for people to move past that.”

Alsen says flashbacks of trauma tend to hit unexpectedly, severely disrupting everyday life.

“And like if you’re walking down the street, and all of a sudden, all you feel like you have a 10 pound weight on your chest and panic, and you have no idea why,” Alsen said. “It could freak a person out, for real. So EMDR really helps actually organize those thoughts. And those memories that get shot up in trauma that could kind of disorganized and when you’re in that fight or flight space, they don’t get stored well. So EMDR facilitates processing of the actual memory and then storing it in the correct spot in the brain.”

Alsen says before a patient gets to EMDR, and accessing deep memories, she first works with them to re-evaluate their self-worth. She calls this “groundwork.” She says it can take weeks, months or years.

“You’re identifying, maybe, what are some core beliefs that aren’t so helpful that may have come from the way that you’ve interpreted your own trauma experiences, right? And then that can keep you stuck,” Alsen said. “Because if you believe I’m no good, then what effort are you going to make in trying to heal yourself?”

Alsen says the saying “find your happy place” is a real tool they use for trauma victims. Therapist Emilia Alsen in her office in the Crime Victims Services Unit of St. Peter’s Health Partners at Samaritan Hospital.CREDIT JACKIE ORCHARD / WAMC

“Like grounding, bringing you back to your baseline,” Alsen said. “So that could be deep breathing, it could be a safe place meditation, where you create this space in your mind that’s beautiful and detailed and rich with you know, senses information. So if I’m in my safe place, I might have really vibrantly green trees, I can smell the leaves, I can hear, you know, the ground that I’m walking on.”

Alsen says a big part of her job is letting clients re-live their trauma and talk about it, often experiencing symptoms of PTSD while doing so, but also keeping them calm enough to function.

“Sometimes it can be look it can look like significant trauma symptoms,” Alsen said. “Like a re-experiencing person might dissociate, they could potentially have a panic attack flashback, they could become dysregulated, cry, become very upset, difficult to calm down trembling, sweating, blurry vision, sweaty palms, all those sorts of things, but they’re really at the max. Because as the thing is, we let people try to figure out how to calm themselves down, after we’ve taught them the tools to calm down, you know, so in this session, in this particular trauma work it’s not ever going to be easy. It’s never going to be clean, it’s never going to be simple. And it’s not going to feel good at first, it’s always going to hurt. It’s always going to hurt at first, but it gets better. So we really have a duty to help these folks really feel it, but also not to the point where it’s too much that they really would be damaged afterwards.”

Memories

Alsen earned her bachelor’s from The State University of New York at Albany in psychology with a minor in counseling and a master’s from St. Rose for community mental health counseling. She says she’s not a trauma expert, but she’s worked with many children and adults who have had childhood sexual trauma and abuse. She says it’s common for victims to suppress the memory of abuse, often for years, until a certain trigger brings all the memories flooding back.

“And then all of a sudden, when they shake up the memory or the memory shakes up itself, it comes up and they are not exactly connecting with it. Because the logic part of your brain is pretty much offline,” Alsen said. “You know, when you’re triggered in fight or flight, it’s really just like your limbic system. And you know, your, what they call the like the old brain, the reptile brain. So all of that doesn’t really help memory, because that’s not where memory’s stored. Memory is stored in the brain that’s offline.”

For example, Alsen says if you were molested as a young child you may not remember at all, or you may present with a variety of symptoms from that abuse.

“So zero to three, you’re not going to have explicit memory,” Alsen said. “From three on you may have explicit memory, which means you can see images of the thing that happened in your own mind. Or you might be able to recall what somebody said or information. So depending on how that child is supported, did they tell anybody? You know, that’s important to know, if they did, what was the reaction? Tell me more about the abuse? Like was it somebody they knew? Was it violent? Was it grooming? Was it confusing? Was it a family member? All of those things play a role in the intensity of the trauma symptoms later down the road. So if you have a child who’s growing up in a place where their parent is sexually abusing them, and there’s no supportive caregiver or the caregiver that’s supposed to be your support is either unaware or you’re unsure about their awareness, that can be extremely confusing for a child. And unfortunately, what it does is that it doesn’t exactly communicate a message of safety. And so if the perpetrator lives in the home, that child is going to be in fight or flight survival mode a lot, which means that the place where they would store their memories, which is, you know, the human part of the brain, the most richly developed, is going to be offline because you can’t think straight. When you’re in fight or flight, it just goes offline, you don’t need it, you need to be able to run, you need to be able to fight, you need to be able to breathe, you need to be able to do all those other body things. So they’re just like, you know, screw executive functioning, it’s offline. And that’s where we would store those memories.”

Alsen says the limbic system isn’t time oriented.

“Because any memory from any time can come together, stuck up, but they can mix together, they can come up,” Alsen said. “And it’s usually something innocuous that might trigger it or something obvious. So let’s say it’s a survivor of child sexual abuse, who doesn’t currently have any recollection. And he’s walking down the street, and then somebody who looks like their perpetrator looks them in the face and greets them. In that moment, a person who has those memories completely repressed, still has the chance that that face to face greeting could trigger something in the brain, there, all of a sudden, this, this random thing comes up for the person that they don’t remember, and boom, it’s right there in their face. That happens actually, all the time. And it happens mostly with individuals who have coped with their trauma through using substances or alcohol. So if you think how hard it must be for a child to work on repressing something over and over, not thinking about it, pretending it didn’t happen, repress, repress, repress, to the point where now there’s like, your brain is taken over psychologically, now it’s suppressed, so you don’t have to work at it. And now it’s just automatically put down, adding drugs and alcohol on top of that, like, keeps it down. But it’s kind of like a spring, you know, it’s like resting on a spring so that when you take the alcohol and the drugs away, it pops off.”

Alsen says the people in recovery from alcohol and substances, the majority of her clients, experience this spring-loaded memory flood the most.

“Folks who have been in active addiction for a long time, and they trace it back to when they were experiencing abuse, whether it was in childhood, teenage years, adulthood, but mostly childhood,” Alsen said. “These are folks who have coped with their childhood abuse, neglect, and victimization via drinking, partying. And then typically what that does is it gets progressive, because that’s the nature of addiction. So then you have this poor, traumatized person that has two very significant issues, a chemical addiction, and then trauma. And because they work in concert, in order to keep the trauma down, you drink more, you use more. But what happens when you drink more, you use more, you make yourself more vulnerable, to being hurt by people that you might not know. So then increase in trauma. And so when you finally arrest the addiction, and you stop, and you try to seek recovery, the first few things that happen while your brain is detoxing and clearing up, is that it comes back — boom, the spring, the weight on the spring has been removed and… pop.”

Alsen says she often asks her clients, “What’s popping today?”

“Because it really is like a popping — people are like, ‘I was walking down the street and then all of a sudden, I smelled the smell. And it reminded me of the perfume that so-and-so used to wear at church and then all of a sudden I was back in the cloister with a clergyman who was abusing me.’ Like it’s that subtle,” Alsen said. “It’s that subtle, which is why people can be so confused. If they don’t have the memory. They’re not worried. They’re not walking through their world actively recognizing themselves as a survivor. And then boom, something strikes them one day out of the blue, it can be terrifying, which is why a program like this is so important. Because if that happens to you, you can call the hotline.”

The hotline is 518-271-3257. Alsen says you can describe your symptoms and memories and trained professional will help to ground you.

“Deep breathing isn’t just some corny thing that counselors tell people to do to fix all,” Alsen said. “Deep breathing is a skill that facilitates problem solving. So if you can deep breathe at least three in a row with your exhale doubling, you can actually calm your brain down to the point where you can actually make a decision. And so when we’re working with people who have trauma and addiction, the most important thing to do is slow down, breathe, calm. Now, let’s sort this out, you know, and prioritize ‘what do we need to tackle today.’”

Alsen says you need to find the right time for you to seek help. But don’t fool yourself into thinking that enough time will pass for your trauma to just float away.

“The sad thing about trauma is that it’s not going anywhere,” Alsen said. “So, for those individuals who are steadfast in avoiding it, I want you to know that that is a hallmark symptom of PTSD. And also, it makes it very challenging to figure out when is the right time. If you have this gnawing feeling at you that this is something that you know you’re not going to get better until you at least bring it up, I want you to know that our program has been here for over 30 years, and we are not going anywhere. So if we’re not going anywhere, and your trauma’s not going anywhere, it means that you get to heal on your time. Give us a call.”

Just Know That We Exist

Lindsey Crusan-Muse is the director of Crime Victim Services.

She says in a perfect world, one of her programs would put the entire unit out of business: the prevention team.

“So we go into schools, whether it be elementary schools, or middle schools or high schools and also work with colleges to go in and really try to prevent crime from happening in the first place.”

Crusan-Muse says the prevention team reaches about 11,000 people a year.

“We’re in a lot of the local school districts, we help them comply with state laws and federal laws related to child sexual abuse prevention. You know, if they have to do training around anti-bullying work, then we do that. So there’s a lot that we can help schools with, and it’s all free.”

Crusan-Muse says about 80% of the clients in Crime Victim Services identify as female, and about 20% as male. She says you don’t have to have insurance to seek help.

“That’s one of the great things about New York State, and it’s actually a national law,” Crusan-Muse said. “So if someone comes in and they have been sexually assaulted, and they don’t have insurance, that’s fine. We actually will bill the New York State Office of Victim Services for their services here in the hospital, specifically having the rape kit done. So it’s, it’s really great too, because even if someone does have insurance, they can actually opt not to bill their insurance and have it billed to the New York State Office of Victim Services. And that’s important, because especially when we’re talking about victims and survivors of domestic violence, they perhaps are on their partners or their abusive party’s, insurance. And so it could present a safety issue. Or let’s say there’s a teenage girl who is sexually assaulted. She’s 17. And she wants to have medical services performed, but she’s concerned about, you know, her parents finding out for whatever reason, perhaps it’s not safe, or she’s just, it’s private, and she doesn’t want them to know. So those folks can actually come in and say to us, ‘I don’t want my insurance billed, I want you to build the Office of Victim Services,’ and we will.”

Crusan-Muse says with the two people on the prevention team, about 35 on the support and advocacy team, the forensic examiners, administrative team and the volunteers on the 24 hour hotline – there are about 100 people waiting to help in the Crime Victim Services unit. And she says they were all hired because they actually care.

“We actually asked questions directly to our candidates about things like, ‘what causes rape,’ because we want to make sure that people have a thoughtful answer, and also that they’re not going to victim blame, because that is not what we’re about,” Crusan-Muse said. “We firmly believe, you know that victims are never responsible for being victimized. And we want to make sure that when folks are walking through the door to get our services, they know they’re not going to be judged. They’re just going to be supported.”

I myself have been raped. It happened while I was living in San Diego a few years ago. I had had too much to drink, I was wearing a really short skirt, I had put myself in a compromising situation. At least, those were all the things I yelled at myself in the mirror the next day.

I saved the underwear, which had been forced inside me, in a Ziploc bag and kept it in my freezer for six months before I threw it away. I never went to the hospital because I didn’t even know where to start. Didn’t know who I would talk to or what they would ask me… or assume about me. I decided the best thing was to move on.

But I think if I had known women like Coons, Alsen, or Crusan-Muse back then… I probably would have gone to the hospital. If I had to tell my story to someone, I’d want it to be them.