Our new season kicks off with an episode that highlights the war experiences of the legendary Rhode Island Regiment, a multiracial combat regiment that served through the entirety of the American Revolution, from the Siege of Boston to the disbanding of the Continental Army in 1783. The regiment saw action at the battles of Red Bank and Rhode Island before being transferred to New York’s Hudson Valley where they took part in the battle of Pines Bridge and an unsuccessful attempt to seize Fort Ontario in 1783. They mustered out of Saratoga later that year.

The episode also tells the story of Isaac Ormsbee, a white private in the Rhode Island Regiment who took part in the Oswego Expedition and mustered out at Saratoga. He would later return to Saratoga on foot, walking from Rhode Island to the Town of Greenfield, to purchase land there. Descendants of Isaac Ormsbee still live on that land today.

Markers of Focus: Patriot Burials: Ormsbee Cemetery, Saratoga County.

Interviewees: Dr. Shirley L. Green, author of Revolutionary Blacks: Discovering the Frank Brothers, Freeborn Men of Color, Soldiers of Independence and Eric Schnitzer, Park Ranger and Military Historian at the Saratoga National Historical Park.

A New York Minute in History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio and the New York State Museum, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by David Hopper. Our executive producer is Tina Renick. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Photo courtesy of Saratoga County Historian.

Further Reading:

The New York State 250th Commemorative Field Guide—Office of State History and the Association of Public Historians of NYS.

Shirley L. Green, Revolutionary Blacks: Discovering the Frank Brothers, Freeborn Men of Color, Soldiers of Independence (2023)

Gary B. Nash, The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution (2006)

Robert Geake, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (2010)

Teaching Resources:

National History Day: “Promises Made, Promises Broken: The Rhode Island First Regiment and The Struggle for Liberty”

Battle of Rhode Island Association: Resources

New York State 250th Commemoration Commission: Educator Resources

Consider the Source New York: American Revolution

Follow Along:

Devin Lander

Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York State historian.

Lauren Roberts:

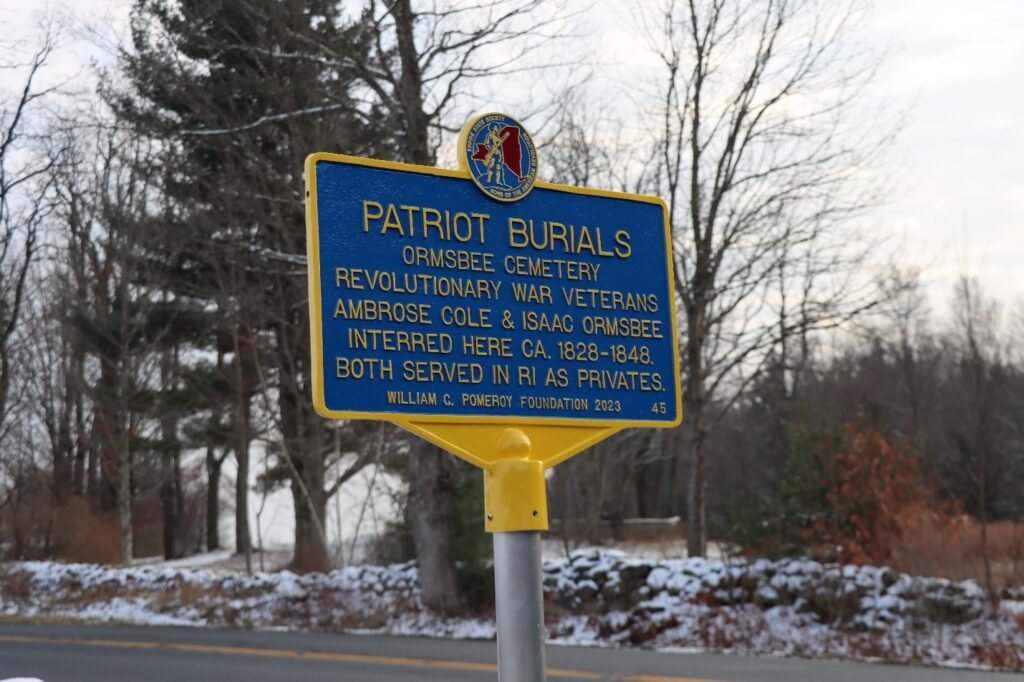

and I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On this episode, we’re focusing on a marker in Saratoga County. It’s located at 299 Ormsbee Road in the town of Greenfield, and the text reads,

Patriot burials, Ormsbee cemetery, revolutionary war veterans, Ambrose Cole and Isaac Ormsbee interred here circa 1828 to 1848 both served in Rhode Island as privates. William G Pomeroy Foundation, 2023.

Now this marker is part of Pomeroy’s partner program called The Patriot Burial Markers. They do this in conjunction with the Sons of the American Revolution, and this allows people to mark cemeteries that have patriots from the American Revolution buried in them.

I think this program is a good way to include a lot of different communities that might not have maybe a specific battle in their backyard or a historic site directly tied to the revolution, but so many of the veterans that fought in the American Revolution moved to other places after the war and settled in small, rural towns, and so these small family cemeteries often hold a lot of really interesting stories, and the Patriot Burial Marker Program gives you a chance to mark these unmarked cemeteries, and it also gives you a chance to delve into some of these individual stories of the veterans that are buried there.

Now the Patriot burial marker program has a few requirements. The cemetery can’t be already marked as having Patriot burials in it. So, if you already have that marker, it would disqualify you from this program. If you don’t, this is a great way to mark a cemetery and to have communities included in the upcoming 250th commemoration of the American Revolution.

Now this marker in particular is in front of Ormsee cemetery. It’s a small family cemetery, and there are two patriots called out, Isaac Ormsbee and Ambrose Cole. And Isaac Ormsbee is the one that we’re going to be talking about today. Not to leave out Ambrose Cole, but his military record is a little more sparse. We know a little bit less about him and his story in the revolution. We know that he was from Barrington, Rhode Island, and he did come to the town of Greenfield in Saratoga and settle alongside of Isaac Ormsbee. But Isaac has a really interesting story.

Isaac Ormsbee enlisted in January of 1781, for three years of service. So, he enlists towards the end of the war, he is with the Rhode Island Regiment. They’re present at Yorktown for the defeat of Cornwallis. And then after that, he is in the Hudson Highlands, and then the Rhode Island regiment comes to Saratoga in 1782 and 1783.

But one of the really interesting parts of his story is that after the revolution, he walks from Rhode Island back to Saratoga to find farmland, and then moves here in the 1790s and he leaves behind a diary that describes exactly the route he took on foot, walking from Barrington to Greenfield, covering 20 to 30 miles a day. He talks about all of the different places that they stop along the way. He even describes stopping in Ballston Spa, which was then Ballston Springs, and tasting the mineral water. He comments on the taste of the water, before he makes it up to Greenfield, where he purchases a farm that’s part of the Kayaderosseras Patent. And then walks back to Rhode Island, where he collects his family and his things, and they move to the town of Greenfield.

And of course, we think that he was familiar with Saratoga, because he was stationed there at Saratoga, which was actually in what we now call the town of Stillwater. And then his family continues to live in the town of Greenfield. In fact, the people that own the farmhouse are still descendants of the Ormsbee family, and the person whose property the cemetery is on, he’s also a descendant of the Ormsbee family. So they have a long history, from right after the revolution all the way through until present day, where they settled. Obviously, the road, Ormsbee road is named after the family. They continued to farm there for quite a long time, and part of the original farmhouse is still located there.

As part of the Patriot Burial Marker Program, we had a ceremony at the Ormsbee cemetery to unveil the marker. We were joined by the family, Mark Young, who was so gracious in helping us to erect the sign. And he cares for the cemetery itself. And one really interesting thing, one of the other descendants, Cy Young, actually has in his possession the spy glass that was used by Isaac Ormsbee when he was serving in the American Revolution, and he brought it out for us to see.

- Clifford (Cy) Young, direct descendent of Isaac Ormsbee, showing Isaac’s spy glass to Tim Mabee of the Saratoga Battle Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. Photo courtesy of Saratoga County Historian.

And Devin, you know that we have been working together on a regional working group for the 250th, so we have lots of the New England states and New York, and we meet pretty often and talk about all the different things that we’re doing for the 250th.

And through that group, I met Lauren Fogarty, who is the program coordinator for Rhode Island 250 and she was gracious enough to arrange for Secretary of State Greg Moore, to send a citation from the state of Rhode Island, thanking us for honoring these Rhode Island veterans. And it was really great. We read it at the ceremony at the Ormsbee cemetery.

It’s been a really interesting journey to find out about this. And I don’t know about you, but when I’m researching about the revolution, there’s so many different things you can delve into, but it’s when you see these personal stories, it’s the individuals that make up the Continental Army that really make it interesting to learn more about. And it’s great when we have a program like Patriot Burials, where we can mark these patriots.

Devin:

I think this is incredibly interesting. And you know, not only the story of Ormsbee himself, which is fascinating, but once we delve into the history of the regiment that he was part of which is mentioned, you know that he was from Rhode Island along with the other veteran, but the regiment that he was part of is actually quite famous. It’s known most regularly as the First Rhode Island Regiment, although it went through different iterations when it’s formed and it was formed as a multiracial unit at the beginning of its formation in 1775. Not segregated. These soldiers were all together in fighting and combat and marching and everything together, whether they were white, whether they were African American, or whether they were Native American, and they could be free born or otherwise. To learn more about the Rhode Island Regiment itself, we spoke with Dr Shirley L. Green, who recently published a book on the regiment told through the story of her own family and her own ancestors, the Frank brothers, who served in the Rhode Island Regiment and were free born African Americans.

Shirley L. Green:

I’m Shirley Green. I was born and raised in Toledo, Ohio. I was a police officer for 26 years for the local police agency, the Toledo police department. I eventually obtained the rank of Lieutenant on that department; I was the first female lieutenant in the history of PPD. After my retirement, I attended graduate school at the University of Toledo and then Bowling Green University, and I got my PhD in history at Bowling Green State University. And currently, I serve as an adjunct professor of history at the University of Toledo and at Bowling Green State University, and I am also the Director of the Toledo police Museum.

Devin:

That’s great. What a career you’ve had two it’s been a long one, two or three careers. That’s great. So, let’s talk a little bit about how you came to this idea of writing this book and telling a portion of your family history through the Frank brothers and how this whole idea come about.

Shirley L. Green:

So, I was always curious about my maternal grandfather. He was quite elderly when I was growing up, and he lived in Massachusetts with his family. I hit my grandmother, and that is where my mother was born and raised, in a town called Lynn, Massachusetts, and we used to visit for most of the summers, we would go visit him, and he had a Canadian flag displayed in the dining room. And I asked him about the flag, and he said, Well, that’s where I’m from. I’m from Nova Scotia, Canada. And I was always curious as to how a black family came to be in Nova Scotia Canada, and that always sat at the back of my mind. So, I was an undergraduate African American class at the University of Toledo. It was being taught by Dr Nikki Taylor, who I believe now teaches at Howard University. But anyway, she was talking about the first great wave of emancipation after the American Revolution. And she started to talk about a group of people known as Black loyalists. And she said many of them, not all, but many of them would eventually leave the United States, the new United States, and eventually migrate to Nova Scotia. And as soon as she said that, my head popped up. I stopped taking notes. And after class, I went up and talked to her about it, and she asked me if my grandfather was a descendant of one of the black loyalists. I said, I don’t know.

So, I went home, and I started to question my mother’s family members, and eventually I talked to the oldest surviving member of her family, my uncle Ben Franklin, and he told me this story. He said that there were two brothers with the last name of Frank who fought with the black regiment out of Rhode Island for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, both brothers started in the spring of 1777, and at this point, Rhode Island was required to provide two infantry regiments for the Continental Army service, and they were the first and second Rhode Island regiments.

The Frank brothers enlisted into the second Rhode Island regiment, which was an integrated battalion, and that battalion regiment was composed of white, black or Native American soldiers, and they had white command officers. And for the Frank brothers, they were receiving the same amount of pay as their white counterparts. When they did receive it, they got the same equipment, they got the same assignments, so they were getting that equality that they had signed up for. But those continental soldiers, especially the first year of their service, were living very tough and rough lives. As I said, the pay was very sporadic due to the limited treasury of the new federal government and the state governments. When they were paid, they got right around $7 a month, which I don’t know what that extrapolates out to, in current terms, right around $200 a month. I believe. They were issued muskets and bayonets. Their issue clothing consisted of hunting shirts or smocks, smocks that were big enough to cover up all the rest of their equipment. Their shoes were always in short supply. I know we hear the story about shoeless continental soldiers, but their shoes were always in short supply in the summer. Sometimes they would go barefoot in the winter. Sometimes they would have to wrap their feet. There is a diary entry from one of the doctors at Valley Forge who said All he had to do was follow the bloody footprints into the winter encampment. It was so bad for them, and they also had to deal with diseases, diseases that ran rampant through those camps. There was smallpox epidemic during the Revolutionary War, which led to General Washington inoculating the troops to make sure that they didn’t die from smallpox. So that’s how tough it was for the brothers that first year.

At the beginning of the war, when General Washington took command of the Continental Army, he basically gave his recruiting and enlisting officers the mandate to not enlist black or black soldiers, and he was concerned about continuing support from the south for the war effort, and he did not wish to

to arm black men to serve in the common army, and that’s whether they were formally enslaved or where they were free born, like the Frank brothers. Um, his hand was pushed. He decided to change his policy when the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation in November of 1770 I’m going to get this date wrong, so I won’t say it, but Lord Dunmore, it’s, I want to say 1775 but I don’t think that’s it. Um, anyway, he proclaimed a proclamation, and it basically stipulated to enslave black and Native American men, that if they came to the British side, that they would gain their freedom if they were willing to fight for the Brits, and around 2000 if that number is correct. It’s pretty tough to determine how many fugitive slaves ran to the British side, but a great number of them did do so, and he was able to start his own black regiment called the Ethiopian regiment. He trained them, he gave them uniforms, and they did fight in a couple of battles for the British side. So, when that happened, George Washington had to react to that, and he also was reacting to some pleas and appeals from black leadership in the in the Revolutionary era America and some of his own command officers who wanted to allow the enlistment of veterans who had already fought in the militia, to allow them to serve an accountant army. So, in January of 1776 he revised his policy and allowed free veteran soldiers to enlist an accountant army. Then in January of 1777 he changed his policy once again to allow all free black men to enlist, and that’s what allowed the Frank brothers to enlist in the spring of 1777.

So, Washington was against arming enslaved people and but because of the circumstances at Valley Forge, general Varnum and other Rhode Islanders were able to convince them that they could go back to their home state and enlist a battalion of slaves. And Washington agreed. The Rhode Island General Assembly agreed as well, and they allowed couple of their a few of their command officers to leave the Valley Forge encampment to go back to the state of Rhode Island and enlist a battalion of slaves. So at this point in time, you have the first and second Rhode Island regiments that are decimated at Valley Forge. Now you have this great influx of formerly enslaved men who are now going to be trained and serving with the Continentals as part of the Rhode Island regiments. And for some reason or another, and I can’t find any written policy that states it, but for some reason, I believe that this is the first case of sanctioned segregation in American military history. Because what happened was the new recruits were combined with over 70 documented veteran, black and Native American soldiers from both the first and the second Rhode Island regiments, and they were all transferred to the newly configured first Rhode Island regiment, and that would become known as the Black regiment. So now you have all of the white soldiers that were initially serving in the first Rhode Island regiment. They all were transferred to the second Rhode Island regiment, and the any black soldiers, or Native American soldiers, like the Frank brothers who were serving in the second Rhode Island regiment were all transferred to the first Rhode Island regiment. So, you have these segregated forces now in the Rhode Island Continentals and they also had white command officers, Ian.

What is really interesting about what happens with the Rhode Island regiments. They started when, when the Franks is enlisted in the spring of 1777, they started with these two infantry regiments that were integrated. You had white soldiers, black soldiers, Native American soldiers, all serving together. Then you have Valley Forge. You have the slave enlistment act. There’s a segregation of the regiments.

And by February of 1781, they have lost more often, more soldiers, I shouldn’t say officers, more soldiers, during this period of time. And they just finally decided that the best thing, the deal, the best way to deal with this, this lack of manpower, was just to consolidate the first and second Rhode Island regiments. So, they became the first and second Rhode Island consolidated regiment, and it was now being led by the original commander of the black regiment, a guy by name of Christopher Green.

And in the spring, the first and second consolidated led by Colonel green. They were in camp in Westchester County, New York, near pines bridge, and their primary responsibility was to guard the continental lines and but in Westchester County, there was almost a daily confrontation between loyalists and patriots, and that area was known to have a lot of guerrilla warfare that was being carried out by a loyalist group that was led by a colonel by the name of James Delancey. The group was known as Delancey’s core of refugees, and they were composed of American born soldiers who were living in Westchester County and had chosen to remain loyal to the British cause.

And at sunrise on Monday May the 14th, 1781, Delancey led his loyalist militia group towards Pines Bridge, and one group would attack the guards at Pines bridge, and another group would attack the headquarters of Colonel Green, which was located at a place called Davenport House near Pines Bridge, and that is where the most brutal fighting occurred at the Davenport House. There, Colonel Green in a small detachment of soldiers from the first and second Rhode Island. They were ambushed there, the major who was in the headquarters sleeping with in the same room as Colonel Green, he was awoken he was shot in the head while he was reaching for his pistols to fend off the attack. Um excuse me, Colonel Green was wounded in the initial attack, and what they did they attached his wounded and dying body, they strapped it to a horse and dragged him about a mile away from the Davenport House. Alright, they eventually left Colonel Green’s body at the side of a road, and of course, it was later buried along with Major Flagg at a cemetery in Westchester County. There is a monument there that commemorates that battle. It is located in Yorktown Heights, New York and Westchester County. Pines Bridge Monument is probably the first Revolutionary War Memorial that depicts a white American and that is Colonel Green, an African American member of the original black regiment and a Native American all fighting together. There’s three statues on top of this monument. It’s an amazing monument. So, if any of your listeners are in that area, they really should go to Yorktown Heights and take a look at that monument. It is an amazing piece of work.

Lauren:

We noted earlier that Isaac Ormsbee enlisted in January of 1781, so he would have been present with the regiment in May of 1781, at the Battle of Pines Bridge.

- Verger, Jean Baptiste Antoine De, Artist. Soldiers in Uniform. United States of America Rhode Island, 1781. [Williamsburg, Virginia: publisher not identified, to 1784] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021669876/.

Everyone knows what happened in Saratoga in 1777 when Burgoyne surrendered to the American troops there known as the turning point of the American Revolution. But after that date, Saratoga kind of takes a back seat to other main players during the revolution. So, we may be wondering, why would the Rhode Island regiment be sent to Saratoga in 1782 much later in the war after Yorktown has already happened. In order to learn more about why the regiment was sent there, we spoke with park ranger and military historian Eric Schnitzer from Saratoga National Historical Park.

Eric Schnitzer:

My name is Eric Schnitzer, I am the park ranger military historian at Saratoga National Historical Park. i.e. Saratoga battlefield. I’ve been at the park since 1997 and I’ve learned a lot over that time. As you can imagine, for decades being in this wonderful place, I’ve always had an obsession with the military events of the Revolutionary War. Ever since I was an elementary schooler and learned about the subject in fourth grade, and then my interest was further spurred when in seventh grade, I learned from a great teacher the broader story. And since then, of course, read and wrote and worked as a park ranger to continue all of that. So certainly, General Burgoyne’s British Army, invading New York from Canada, surrendered in October of 1777, at Saratoga. When we say at Saratoga in an 18th century context, we are typically referring to what is now known as the village of Schuylerville. So, when Burgoyne’s army surrendered there in Saratoga, i.e. Schuylerville in 1777.

No longer would you have massive invading armies coming out of Canada trying to quell the unnatural rebellion of these revolutionary Americans. You know, from the north, it wouldn’t happen again. The British had learned their lesson the hard way with the surrender of the first ever British Army in World History, General Burgoyne’s Surrender at Saratoga. Now the British forces would never strike directly at Saratoga. They didn’t do so because Saratoga was really kind of the hub, the strongest hub, that the Continental Army held north of Albany. It had been Saratoga garrisoned by Continental troops since the very beginning of the war in 1775 and would be throughout the remainder of the war, through December of 1783 there was always a Continental Army presence in Saratoga. But even after we’re going surrender, Saratoga was the northern most permanent outpost of continental troops. And so, you always had a presence there. I’m not saying you had 3000 troops there at any time, but you would always have a cadre of Continental Army forces. They would have a barracks there, block houses, of course, a supply depot, at times, the commander of the Northern department of the Continental Army, let’s say John Stark, later in the war, his space of operations was in Saratoga. So, Saratoga was a stalwart northern most defense for the Continental Army operations.

Lauren:

So then, why was it, if there was always a presence there…What happened in 1782 that had the Rhode Island regiment moving up to Saratoga?

Eric Schnitzer.

When they were ordered to go to Saratoga in October of 1782 when they actually got there, in November of 1782 that regiment had been present with the main army for a couple of years already, and so now it was time for them to replace another regiment that had been doing the duty. So, it was just part of the cyclical deployment operations of the Continental Army, and it happened to be that the Rhode Island Regiment was the regiment selected. There is no known reason why the Rhode Island Regiment was chosen, as opposed to some other unit. There’s no known documentation or thoughts written down by anybody that informs us why that regiment was chosen as opposed to another.

Lauren:

So, the Rhode Island Regiment is pretty famous for being an integrated regiment. I’m wondering if you could just talk a little bit about what those demographics looked like while they were at Saratoga

Eric Schnitzer:

The Rhode Island regiments of which there were two, formed in 1777 late 76 early 1777 were racially integrated. But then in starting in 1778 Rhode Island decided that they were going to actually segregate their two regiments. The first regiment would be black only insofar as the enlisted personnel. You’d have white officers, commissioned officers, but black men would be in the ranks. And then the second regiment was racially integrated, and it didn’t work. It did not work. And so, by 1781 at the part of 1781 Rhode Island decided that what they needed to do was combine their two regiments into one, and that’s where we get the Rhode Island regiment. When the regiment arrived in November of 82 at Saratoga. It effectively was organized like this. It consisted of six subdivisions or companies. Of these, four of the companies were white companies. One of the companies was a black company, and the sixth company was racially integrated. So, it was uniquely that no other regiment did this in the whole war. It was uniquely interest segregated, but it had an integrated company within the interest segregation of the unit. Very strange. Now you asked about numbers. If we look at the percentage of non-whites in the Rhode Island regiment at this time, it was about 20% which is pretty substantial. Most regiments, and it varied regiment to regiment, of course, and it differed during the course of the war, etc. But the best we can we can view when it comes like to racial integration in the Continental Army broadly throughout the whole course of the war, you’re looking at an average of somewhere between five and 8% of any regiment at any given time, on average, was nonwhite, and

in this case, it’s almost 20%.

Devin:

One of the things we do as historians is attempt to uncover new information and new resources about the past that will lead to new discoveries and new interpretations of past events. This discovery and reinterpretation of the past is specifically true with relation to the Rhode Island Regiment itself, which was thought to have been involved at the Battle of Normanskill, but as Eric Schnitzer tells us, that could not be true.

Eric Schnitzer:

The Battle of Normanskill. So, I think we all know that there is within the town of Guilderland a wonderful blue and gold marker, a sign there, and it tells us that there was this battle of Norman skill, fought in August of 1777 and it involved the suppression of a Tory rising, which is true, and that it involved Schenectady militia, which is true. And I think it says 40 Rhode Island troops. Now, when I became aware of this sign years ago. I thought to myself, knowing how, in 1777 especially how the army was organized, where the various regiments were and everything, I thought there were no Rhode Island troops anywhere even close to Albany or the Normans kill or anything like that. So, there’s no way that just couldn’t be I looked into it in deep, did a deep dive in the military, you know, deployments and everything. And, of course, the two Rhode Island regiments, because we have to remember, there were two. They were downstate in the, you know, the Peekskill area. They were way down there. And it wouldn’t be long before they would be ordered to join George Washington’s army in, you know, to try to defend Philadelphia, ultimately. So, the regiments were down in Peekskill. There’s no question about it. There was no detachment you can and the idea that you would have a detachment go from one department, i.e. the Hudson Highlands department, and traverse the boundary of the Northern department without the orders of the commander in chief to put down a dozen, you know, loyalists, is crazy. It’s not a thing. And so, I looked into the primary source material, and it’s very clear that the 40 Rhode Islanders were, in fact, 40 Massachusetts Continental Army soldiers. What had happened was the Schenectady County committee was informed of this gathering, and so what they wanted to do was form a body of Schenectady militia to put them down, but they didn’t know if that would be enough, because reports were like they were in the hundreds. And so, we got to match their numbers. And so, the committee requested that the Continental Army Detachment in Schenectady augment their numbers for this little expedition, and so they called upon the senior Continental Army officer located in Schenectady at the time, a captain by the name of Abraham Childs. Now Abraham Childs was one of the eight captains commanding one of the eight companies of what was called Colonel James Wesson’s later known as the ninth Massachusetts Regiment. That regiment had its subdivisions, its companies, strewn throughout the Mohawk Valley at the time. This is in advance of the battles of Saratoga, when the regiment was consolidated and went up to ultimately fight in the battles of Saratoga, which it did. Child’s company was in Schenectady. He was requested by the committee to have you know himself, lead a detachment of his company and helped quell this rising in what became the Battle of Normanskill. It’s really an over glorified skirmish.

Lauren:

While at Saratoga, even though it was towards the tail end of the war, the Rhode Island Regiment was ordered to take part in the ill-fated Oswego expedition.

Eric Schnitzer:

So, in the beginning of 1783, I mean, the last year of the war. You know, things are expectedly winding down. You don’t have the declaration of secession of arms yet, but that’ll be a few months off. It came to the mind of Marinus Willett that we should mount an expedition against Fort Oswego. Fort Oswego in Oswego, New York, right at the outlet of Oswego, the river there into Lake Ontario. And the idea was that, well, there was a British base of operations there, and we ought to attack them in the winter when they least expect it, because it worked at Trenton. So, let’s do it here in upstate New York. In 1783, they never made it. Their guides got them lost, and the snows, deep snows, freezing temperatures, they ran out of food.

All of these things hampered their progress to the degree that Marinus will it ordered the troops to be returned back. But it didn’t end there, because, obviously, the regiment was based in Saratoga in the winter of 82-83 but then they were also based in Saratoga at the end of 83 when you have the beginning of the winter of 83-84, well, this is when things were winding down. The war was winding down. Half the regiment had been discharged in June, and so the cadre of somewhere around 150 plus soldiers left behind, officers and soldiers left behind in Saratoga were really left out on a limb by the state of Rhode Island for the rest of the year. The Congress and the state of Rhode Island barely even noticed them because, you know, it’s the end of the war. Well, you know, the war is going to wind down. They’ll be discharged soon. Why should we spend money to send them blankets or shoes, even though they don’t have any many blankets, and many of them are already barefoot because they’ve run through their shoes, because their shoes are made of leather. And those things don’t last long, you know?

And so, you had many, many soldiers at Saratoga suffering freezing conditions barefoot in December of 1783, because the state and the Continental Congress just wasn’t supplying them. I gotta say, this is a running theme that you have throughout the whole war, from beginning to end, Congress and the states or colonies before them not readily or appropriately supplying the regiments under their auspices. This is a running theme. So, this is not like the Rhode Island regiment was targeted. And if I may also add, this was not a black and white issue, so to speak. This the you had white men and black men suffering at Saratoga because they had to reorganize themselves, because now you’ve just half the regiments gone. So, we gotta consolidate the regiment into a more manageable establishment. So, they decided to organize for the second half. The latter half of 1783, the Rhode Island regiment consisted of two companies, not six. They went from six to two companies, and those two companies, one was a white company. The other was a racially integrated company. And so, you had black men and white men still there, but the proportion was actually still of black men, and let’s say nonwhite men, because it wasn’t just black men. You also had some indigenous people of indigenous descent that were in the ranks of the Rhode Island regiment and other regiments too, not just the Rhode Island regiment, but regiments in New York, New York, New England and broadly other states also included indigenous people and their descendants as well. And it approached 25% in December of 1783 nearly a quarter of the Rhode Island regiment that was remaining in Saratoga were nonwhites, which is, I think if I’m not mistaken, I could be wrong. I don’t think I am. I think it’s the highest percentage seen by any singular Continental Army formation in the entire Revolutionary War. Insofar as racial composition.

Lauren:

Now Dr. Green mentioned that her research into the Frank brothers all started with her grandfather’s Canadian flag. Let’s find out the rest of that story.

Devin:

What about Ben Frank and maybe, maybe this will bring us back to your grandfather’s Canadian flag. But what happened to Ben Frank, you made the connection.

Shirley L. Green:

So, Ben’s story is, it’s wow…it’s an adventure tale, I think, and as we were trying to make the connection between the Canadian Franklin family and Ben Frank, it got to be very, very difficult. But there was a curator at a Nova Scotian museum who brought to our attention the muster role from a black loyalist who had migrated to Birchtown, Nova Scotia after the end of the war.

And they indicated that there was this one gentleman on one of the list who was the same age that Ben Frank would have been at that period in time. But this gentleman’s name was Frankham, not Frank. Now Ben Frank, and all the records that I have where he would have been able to sign his name. No, he always marked with an X, so he was not literate enough to sign his name. So, if he is giving his name to an individual to write down, it might sound different than Frank. It may sound like Frank on, or he may have purposely said that his name was Frankham there is at the end of the war, Ben Frank winds up, I believe Ben Frank winds up in New York, with the rest of the loyalist as they’re waiting to understand the outcome of the Paris Peace Treaty talks.

What is going to happen to all these individuals I mentioned earlier about Dunmore’s Proclamation, many enslaved blacks ran to the British lines because of that, including women and children, to gain their freedom at the end of the war, British officials in New York stipulated to General Washington that we are going to hold on to our promise to these individuals since they came to our side during the war, up to a certain time period, we are going to grant them their freedom. We will, however, compensate their former slave holder for their losses. How are they going to do that? Well, General guy Carlton, who was in charge of the British forces in New York, planning the evacuation of these loyalists, came up with an idea of compiling an inventory of the blacks who were behind British lines by a certain time period. And that book became known as The Book of Negroes.

There has been a mini-series on CBC, Canadian Broadcasting Company a few years ago based on a novel by Lawrence Hill. It was originally titled The Book of Negroes. But what all the blacks who were behind British lines had to do was present themselves to a commission that was formed by General Carlton and explain to who. To this commission, who they were, who that their former owner was, or if they were already free. And Ben Frank I believe, is listed in the Book of Negroes. And this is where the curator from the Nova Scotia Museum was pointing us to, I believe that he is listed in the Book of Negroes as Ben Frankham.

So, he gets on a ship with other loyalists, and black loyalists included, and they sail out of New York up to Nova Scotia, Canada. Ben Frank spends been, excuse me, Ben Frankham serves a period or stays a period of time at the black settlement of birch town, which is in the southern part of Nova Scotia. Birchtown at that point in time, became the largest free black settlement in the Americas. Ben spent a little bit of time there, and then he eventually migrated to the Annapolis region of Nova Scotia. It’s on the western side of the peninsula across the Bay of Fundy from Maine, and he remarried. He remarried in to the family of another black loyalist, and he started to have children. He is easier to trace in Nova Scotia because of the record keeping for the loyalist cause, because loyalists and black loyalists were always petitioning the government for their land. This promise of land comes back into play, and black loyalists were constantly petitioning to get their fair share of land, which, for the most part, they did not receive. And because of that, about two thirds of them would leave Nova Scotia and settle in Sierra Leone and start the black settlement there in Freetown in Sierra Leone. Ben Frank wasn’t one of them, and at this point in time, when he is among these other black loyalists who are petitioning for land, his name has changed again. He has now been Franklin, and that name stuck. And when we initially went to my grandfather’s hometown, the Annapolis Historic Society has multiple binders of the genealogy of black loyalists that lived in that particular region. And when I initially the first research trip that I made up there, I was presented with the binder that had the Franklin family in there, and I found my grandfather’s name towards the bottom of the list the family tree, and then pushed all the way back up, and the first name at the top of the Franklin genealogy page was Ben Franklin.

So that is the connection that goes back to my grandfather having Canadian flag in his dining room.

Devin:

One of the joys in speaking with Dr Shirley Green was the fact that, as she mentioned, she was a retired police lieutenant, on top of being a PhD in history, and as a historian, I’ve long heard and been told by teachers over the years that history is a lot like detective work. We’re detectives of the past. So, I couldn’t let this opportunity pass without asking Dr Green what she thought about historians being similar to detectives.

Shirley L. Green:

Yeah, yeah, I believe it did. You have to be persistent, right? And you have to be open minded and willing to look at all of the evidence that’s out there to close a case, right, or to make a case that’s going to be proven in court. So, you know, for my dissertation, it’s, you know, the case I have to prove to the dissertation committee, and have to be able to articulate, articulate what your argument is and what your findings, what the results were of that investigation. So definitely, I think I looked, I took those skills that I learned as a supervisor of investigations and what I expected from the investigators that were assigned to me, what I expected them to do and show in their own investigative work. So, I looked at the research like that. It’s, you know, solving a mystery.

Devin:

Thanks for listening to A New York Minute in History. This podcast is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio and the New York State Museum, with support from the William G Pomeroy Foundation. Our producer is David Hopper, a big thanks to Dr Shirley Green and Eric Schnitzer for taking part. If you enjoyed this month’s episode, make sure to subscribe on your favorite podcast platform and share on social media to learn more about our guests and the show. Check us out at WAMCpodcasts.org

We’re also on x and Instagram as @NYHistoryMinute.

Devin and Lauren:

I’m Devin Lander and I’m Lauren Roberts until next time…Excelsior!