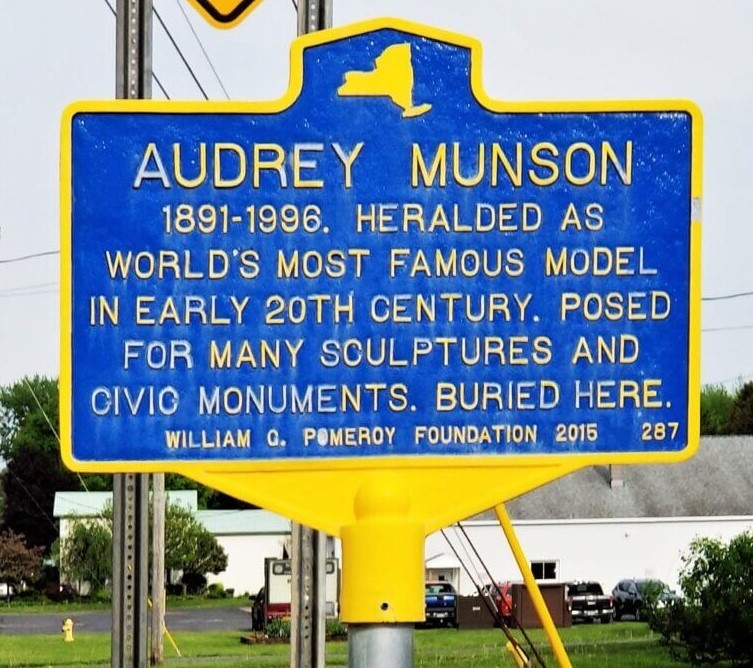

In this episode, Devin and Lauren research the life of Audrey Munson, America’s first supermodel. Born in upstate New York, Munson was one of the most famous models of the early 20th Century, and posed for the top American artists in the Beaux Arts movement. Sculptures based on Munson dot the landscape of New York City, and are held in museums around the country. She was also one of the first American actresses to pose nude in a major motion picture. Once called “Miss Manhattan,” Munson’s life would take a tragic turn by the age of 40. In 2015, the William G. Pomeroy Foundation erected a historical marker near her final resting place in New Haven, New York.

Marker: Audrey Munson, 4233 St. Rt. 104, New Haven, NY

Guests: James Bone, author of The Curse of Beauty: The Scandalous and Tragic Life of Audrey Munson, America’s First Supermodel; Diane Rozas, co-author with Anita Bourne Gottehrer, of American Venus: The Extraordinary Life of Audrey Munson, Model and Muse; and Justin White, Oswego County historian

A New York Minute In History is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King, and features “The Entertainer” and “Unease” by Kevin MacLeod. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

- The Curse of Beauty: The Scandalous and Tragic Life of Audrey Munson, America’s First Supermodel, James Bone (2018)

- American Venus: The Extraordinary Life of Audrey Munson, Model and Muse, Diane Rozas and Anita Bourne Gottehrer (1999)

- “Audrey Munson: The Venus of Washington Square,” David Owen, The New Yorker (December 23, 2019)

Teacher Resources:

- New York City Permanent Art and MonumentsThe Center for Women’s History: Teaching Women’s History with Primary Sources in the Classroom.

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. We’re going to the movies today – but really we’re talking about a William G. Pomeroy historic marker in Oswego County. This one is in New Haven, outside a cemetery on State Route 104. And the inscription reads: “Audrey Munson. 1891-1996. Heralded as world’s most famous model in early 20th century. Posed for many sculptures and civic monuments. Buried here.”

Audrey Munson is widely considered America’s first supermodel, but maybe not in the same sense we think of a supermodel today. She was the muse behind many of the country’s civic monuments, especially in New York City. She’s said to be the model behind the “Walking Liberty” half dollar, and she also had a silent film career. But while you’ve probably seen Audrey Monson before, you may not have heard of her – at least, I hadn’t heard about her before this.

Devin: I had never heard of Audrey either. I was struck, immediately, when we read the text, that she’s a supermodel at a time when that term was very new, if it existed at all, really. She lived an extraordinarily long time, and an extraordinarily interesting time. So when we dug into this topic, we found out that, as with so many of these markers, they direct us to topics that are extremely deep and extremely complex. And the Audrey Munson story is certainly that.

So one of the first people we spoke to was James Bone, the author of The Curse of Beauty: The Scandalous and Tragic Life of Audrey Munson, America’s First Supermodel.

James: I’m originally British, but I’m an adopted New Yorker. I was at university in New York, and then I became a newspaper correspondent in New York. And for 22 years, I was the New York correspondent of the Times of London newspaper…How’s the audio quality? I’ve got builders working across the street…

Devin: James joined us on a call from his home in London, and told us a little bit about how he came to be interested in Audrey as a subject.

Audrey Munson was the model for the 25-foot statue “Civic Fame” by sculptor Adolph Weinman atop the David N. Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building. (Photo courtesy of the NYC Department of Citywide Administrative Services)

James: I have a friend who lived in a loft in Soho, and she looked out at a statue which is on top of the municipal building – and way up at the top of that is a gold figure of a woman. It’s called “Civic Fame,” and it’s actually the second largest sculpture of a figure in New York City, after the Statue of Liberty. My friend had looked up what little she could learn about that sculpture, and she’d seen a reference to the model, Audrey Munson.

And so I took a look at it, and honestly, I wasn’t really prepared for the embarrassment of riches I found when I looked at Audrey Munson’s life. She’s not just in that statue, she’s in many of the statues in New York: the Strauss Memorial up at Western Avenue and 96th Street…in Columbus Circle, the main monument…if you go to the Brooklyn Museum, “Miss Manhattan” and “Miss Brooklyn” – I can go on and on, there were so many. I suddenly realized I’ve been living in this city, and here was something all around me that I hadn’t seen.

Devin: Audrey was born on June 8, 1891, in Rochester, New York, and died on February 20, 1996 – just a few months shy of 105th birthday. [Her family] would eventually settle in the village of Mexico, New York in Oswego County, a very rural area. Her parents divorced when she was young, and her mother, Katherine, who was known as “Kitty,” moved with Audrey to Providence, Rhode Island, where [Audrey] took music and dance classes.

It was pretty clear that from a young age, Audrey was interested in becoming some sort of performer. And at that time, of course, performers normally would work on the stage. The film industry was extremely new at this time in the early 20th century, so if you were a performer, chances were, you’re going to be some sort of dancer or singer on the stage.

Lauren: So how did she go from being an unknown in Providence to being a world famous model?

Devin: One of the things that I found really interesting about reading James’s book and speaking to him was that Audrey did have some level of success. She was in a chorus line when they lived in Providence, and actually, that show toured the country. New York City was, obviously, the center of the entertainment industry, then as it is now. And they moved there really to pursue a career for Audrey – which she did find some work on Broadway. Again, it was ensemble-type work. But how did she become famous, and how did she become a model? It’s a really interesting story.

James: She was shopping with her mother. Her mother used to chaperone her everywhere. I mean, this is a beautiful 18-year-old girl in the big, bad city. They noticed that they were basically being stalked. They noticed a man following them as they were shopping. And finally they ducked into one of the department stores and waited for the guy to go – but he didn’t go, he waited outside. So finally, Kitty went out to confront him. He very politely introduced himself as a photographer (and that was a new thing at the time). He asked that Audrey come and model for him.

Devin: Now that sounds kind of sketchy, and [it] certainly sounded that way to Kitty and Audrey. But for whatever reason, they agreed to go to his studio, and realized that he was a legitimate photographer, which was not a common thing at this time. And it was really through the photographer that Audrey was introduced to the world of art.

James: And she was actually quite lucky with her entre into the art world, because they were a lot of charlatan photographers and artists around. You know, rich dilettantes who, a good way to get close to a girl was to ask her to come back, look at his etchings, and then ask her to take her clothes off and sketch her. This photographer wasn’t like that. He was doing ensemble modeling of women in draped materials and gowns and things like that – that look rather like classical paintings, but they were in the new medium of photography. So that was his thing, that was his angle, really.

But they do seem to have, anyway, fallen in love. It seems that he did, anyway, want to marry her. But then he was much older, of course. And he went into Roosevelt Hospital for an operation and unfortunately died. Something went wrong, I guess – surgery in that period often went wrong, and still does. But he had already introduced Audrey into his circle of more serious friends. Although Greenwich Village was the center of the art world, there was a satellite community in what’s around Lincoln Center now. And so Audrey got involved in the artists up there first of all. One of them was a Viennese sculptor called Isidore Konti. He was the first person who convinced her to pose nude.

It was uncomfortable work. There’s one story, for instance, of Audrey posing for the statue that’s now on the Manhattan side of the Manhattan Bridge. And it was extremely cold in the studio. You can imagine what a studio in Chelsea is like in winter. So Audrey basically organized for the studio assistant to go out and buy coal to fill a brazier so they could have a brazier going while she was posing.

There was another incident that she recounts, where the painter wanted her to stand under a cold waterfall, because he wanted to paint her standing under a waterfall. And she didn’t want to. He apparently pulled a pistol on her and told he would kill her if he didn’t stand under the waterfall.

And then the other thing is the actual process was quite arduous. So for instance, when you cast a woman in plaster, as some of the sculptors did – she described standing there, and there were two men: one has a bucket of warm plaster of Paris with rags, and the other one takes those plaster-soaked rags and wraps them around starting at Audrey’s feet. [He] wraps them all the way up her legs, and around her hips, and around her torso, and around her breasts, and finally gets up to her face – and they have to put a little silver pipe in her mouth so she can still breathe. And of course, the important thing, which Audrey complained she didn’t do properly, is that you have to breathe in before the plaster sets – because if you breathe out, you won’t be able to breathe in again.

That was extremely uncomfortable, as you can imagine. [She] was at least lucky in that she had serious artists working on her. You had to fit the bill for the artists, and they had this classical ideal, basically to do what was done in ancient Greece. And Audrey, for her slightly elongated features, did look, as one artist said, “Grecian.”

Lauren: I think that one of the things that really helped her get her foot in the door with these famous sculptors was her willingness to pose nude.

Devin: Yeah, absolutely, I agree with that. First of all, it was scandalous. It was something that really stuck with Audrey her whole life. There was criticism of her, and of nude models in general, and of artists for depicting women in the nude and men in the nude in some cases. You know, reading about her, and reading some of the things that she wrote about herself – she always had in the front of her mind that this was art. She didn’t look at it in a scandalous way, or a sexualized way, either. In fact, she, at one point, in writing, encouraged women to not wear clothes at all, because clothes were restricting to women and that “true beauty” can only be found in the nude.

I think she saw it as a way to enter the art world, for a person who may not have been an artist herself. She made money. She wasn’t, by today’s standards of a supermodel, she wasn’t making that kind of money – but she certainly was making a living, and she was supporting herself and her mother, who always lived with her. I think she made the decision, consciously, that this was something that she could do professionally to become part of the art world and become part of the scene in New York City at the time.

Lauren: Audrey really hit New York City at the right time, because the Beaux Art style was really in fashion at this point. There were a lot of movements to try and create these civic monuments that were based on what was called “the ideal woman,” which were the characteristics that Audrey possessed.

Devin: That’s a great point, Lauren, and it’s actually something I asked Diane Rozas about. Diane is the co-author of the book, American Venus: The Extraordinary Life of Audrey Munson, Model and Muse. I asked her why the Beaux Arts movement developed with such dominance in early 20th century New York.

Diane: Beaux Art was brought to the U.S. from Europe. The thinking behind Beaux Art was to create beauty throughout the city to commemorate important events. And if you go to Paris, if you go to London, especially France, you’ll see this consistency of beautiful statuary and monuments.

In New York, it was already well-established. Besides commissions, private commissions, they did these monuments. So that involves an architect and a sculptor working together to create something that was not just a slab of stone, but rather something that would be lasting, and that would be a place that people wanted to go – to look at, to understand, and to remember. So the Beaux Art period was meant to be more than just a representation. It was meant to be a grander idea.

But the truth of the matter was that the art world was changing, evolving. And all the artists she posed for were old. They were old.

James: One of the reasons why Audrey has been so forgotten, and all the artists she worked for, really, have been so forgotten, is that they were completely swamped by modernism. The modernists arrived in America – normally I date it to the 1913 Armory Show on Lexington Avenue, where you had the leading European modernists show for the first time in America.

Only one of them actually came, Francis Picabia. And he was very interested in the idea of how you represent motion in painting. A completely new concept – when Audrey went to pose for him, he told her to move all the time. I was able to attribute that painting from those sessions. I actually identified which one it was – and it’s completely abstract. You wouldn’t guess it was a woman. Audrey didn’t like that kind of stuff at all. She was very conservative in her taste, and she called [modernism] a “congruous collection of color splotches.” It’s not the kind of thing you need somebody to sit there for hours to reproduce them.

Lauren: Lucky for her, at that time, the new silent film industry was really up and coming in New York.

Devin: Audrey ended up making three films during this era, the first being Inspiration in 1915, which was made in New Rochelle, New York. We have to remember that at the time New York was the center of the film world in the United States. This was pre-Hollywood. But anyway, Inspiration came out in 1915. And in it, Audrey played a sculptors model, which makes sense. And she was one of the first American actresses to appear in the nude in a non-pornographic film.

Lauren: I think that posing, you know, that’s the way that she wanted audiences to see her.

Devin: That’s true. And for whatever reason, the studios didn’t think she was a good actor. She did have an [acting] double in at least one of the films. Most of the films tried to portray her life [as if] a biography of her, or other ways to incorporate the fact that she was a model, to get her to be able to pose in the nude. And she was willing to do that, and at least the first two films were hits as a result. Again, she’s extremely famous at this point.

But overall, I think her experience in the film industry was not a happy one. The third film she made during this era was called Girl O’Dreams, and was actually completed in 1916, but never released. In fact, most film historians say the film was never even viewed. She ended up suing several of the film producers for missed payments and for money that she felt she was owed. She didn’t like the fact that she had a scene double. Also coupled with this was the Wilkins scandal of 1919.

James: Having had a mental breakdown and come back to New York, she put herself, it seems, under the care of a quack doctor called Walter Keene Wilkins. He had a place on 65th Street, which were her old haunts, up by Lincoln Center there – that whole area we were talking about before. She had a room there. He was on his third wife, and ended up having an argument, possibly about Audrey, and the doctor’s apparent obsession with Audrey, with his wife. And [he] ended up smashing her head in with a hammer, killing her. He was sentenced the electric chair, and before he was moved upstate to Sing Sing to be fried, he ended up hanging himself in his cell in Nassau County Jail.

There’s no evidence that there was any sustained relationship between Audrey and the much, much older Dr. Wilkins. But the press speculated a lot about that. They called it the “eternal triangle,” the love triangle. She was a famous celebrity, it was a scandalous case. And one of the reason she retreated back up to Syracuse, back up to Mexico was to avoid the fallout from that case.

Lauren: I think we see a couple things coming together here. First of all, you mentioned the change in the style of art, where Audrey really wasn’t the most requested model anymore, because her kind of classical style was not in the forefront in New York City or in other places in the country. She wasn’t really happy with how she was treated in the film industry. And then finally, we have bad press, and when you’re in the public eye for so long — and she was so young at the time — there’s only so much I think you can take. And we start to see the decline in her mental health, and her ability to hold it all together.

Devin: Eventually, her and her mother moved to Mexico, New York, and she does try a couple comebacks. She does star in another movie. She also wrote an advice column, beginning in 1921, that was published widely. There’s some evidence that that may have been ghostwritten. But either way, it got her name out. It seems that those types of things didn’t last. And you know, she was forced to come to the conclusion that she wasn’t going to be famous anymore, and I think that was really damaging to her.

But I’m curious, because I know that this is a part of her life that you investigated thoroughly. What led to her eventual institutionalization?

Lauren: Yeah, I mean, you can almost imagine: she has to leave New York City, her comebacks have not worked, they’re struggling for money. And in this town, it was known what she had done in the past, that she had posed nude, and it seemed like it was even less accepted in this part in New York than it was in New York City. She really felt ostracized, and this kind of downfall certainly added to her depression and anxiety.

It did lead to a couple suicide attempts. And her mother felt that she couldn’t take care of her anymore, that she was a risk and she needed some medical care. Kitty at this point was still by herself, she never remarried after her divorce. So on Audrey’s 40th birthday, her mother institutionalized her, and she was put into the state hospital up in Ogdensburg, New York. And that’s where she lived for the final 65 years of her life.

I was lucky enough to talk to the Oswego County Historian Justin White, and Justin’s family had a close connection to Kitty Munson.

Justin: Audrey’s mother had been working as a housekeeper and a nurse, and she figured that it would be better for her to move into the city of Oswego. This is when she met a couple named Thomas and Lucy Starrett, and they became very friendly with Kitty and offered the upstairs of their Victorian home. My great aunt and my great uncle got married in 1948, and they were friends with Tom and Lucy as well. They need a place to stay as newlyweds and [Tom and Lucy] said, “Well, you’ll have to live with this elderly woman that we’re taking care of. And maybe you can help us, too.” So they shared the second floor with Kitty. They did periodically take her to Ogdensburg, but it was about 100-plus mile trip.

Kitty thought that [Audrey’s institutionalization] was a temporary situation, but it turned out not to be. But after a while Audrey was treated very well. She had good experience with her roommates. Some of the people that we have met through the years that took care of Audrey have discussed how beautiful she was, and how kind she was. They said that she was their celebrity patient.

Lauren: I think it’s important to note that she really felt like the institution was her home, it was her refuge. Being in an institution, where life was very steady, was probably comforting to Audrey. Audrey herself limited the people who were able to visit her. She was really worried that reporters and journalists were going to come in to try to see her mental health problems and her institutionalization. So she really didn’t allow any visitors in, except for family members – and Kitty was the only family member that she was close with.

She had a kind of falling out with her father. It seems like he was maybe embarrassed of her being institutionalized, so he really didn’t have any contact with her. Her father had gotten remarried and had more children, and some of those children didn’t even know that Audrey existed. Part of the story of Audrey being there is known because at the end of her life, she actually reconciled with a few of the family members.

Justin: Audrey reconnected with her half-brother and his daughter, Darlene. He just said one day at the family dinner, “I wonder what happened to my sister Aud.” He pronounced as “Aud” and they said, “Who is Aud?” “My sister Audrey.”

“Tell us more. Is she still alive? Where is she?” And he did not know at that moment in time. He hadn’t seen her since he was a little child, and before he passed his dream was that he would be able to find out what happened to her – and if she were still alive at the time, that they could reconnect. So back then, with the HIPAA laws, it was very difficult for Darlene and her sister to seek out Audrey.

They also had to address the question to Audrey whether she wanted to accept the visitation. And at first she said no. But the staff and the doctor said “We think this would be good for you.” So she allowed to see her brother. They celebrated her birthdays – obviously they were able to do that because she lived to 104. At one point, she no longer needed to be a patient, and they moved her further north to a nursing home – but she did not feel comfortable there. And they decided, “You know what? She better go back to her refuge.” And that’s where she remained the rest of her life.

Devin: So after Audrey passes away, she’s initially buried in an unmarked grave, right?

Lauren: Yes. So when Audrey died, her niece, who she had become close with, took possession of Audrey’s ashes. And she really wanted to bury her with her mother, Kitty. But at the time there was no “Find a Grave,” it was difficult, and her niece couldn’t find the location where Kitty was buried. Kitty’s also in an unmarked grave – remember, she didn’t have a lot of money at the end of her life. So it ended up that the niece put Audrey’s ashes in with her father in the New Haven Rural Cemetery.

And the reason there was no marker there was because there already was a stone for her father. And the cemetery rules did not allow for another marker that would block what was already there. So unfortunately, they weren’t able to put a marker at that time. Now that has since changed, there is a flat marker where Audrey is buried now – but it’s not a very prominent marker, and it’s not something that, maybe, we would think fitting for one of America’s first supermodels.

Devin: Which brings us to the Pomeroy marker, which was erected in 2015, and really is an attempt to give Audrey the recognition that she deserves.

Justin: She revolutionized the motion picture world. She transformed how women could present themselves, and control their own lives. She became the most famous woman of her lifetime in the art world. An American Venus, an exposition girl, “Miss Manhattan” and queen of the artists’ studios.

Diane: To me, she was an artist herself, and it’s all over New York City. Sometimes you see a person on the street and you feel drawn to them. And I felt that for a statue.

James: It was brave of her to pose nude, and she was a serious person. She did take her job seriously. But she’s a life of success, and she’s also a life of failure. Right? It’s like, there’s only one feminist narrative, which is you can only write about women who are successful, and overcome the odds and become great successes, right? But to me, that’s not really history. I mean, take somebody’s life and just tell the story of their life in all its complexity, the way it is.

Lauren: One of the main takeaways from Audrey’s story, for me, was that it’s so easy for people on the outside looking in, on what appears to be a glamorous, star-studded life of a supermodel. But maybe that glitter blinds us to the unbelievable pressures those individuals are faced with every day, especially when they’re female. It was really, a pretty short time that she was seen as perfect. And I think that says a lot about – and even today – a lot about how short-lived the female body is seen as perfect. I think you can see that in the entertainment industry, whether it’s an actress or a singer, dancer – you have that really short window when the body is idolized, and then it goes away. And what happens to those women?

Devin: I think that’s a great point, and you’re right that it continues to happen. Audrey’s story is not unique in that regard.

Also, what I found interesting, as we were doing research for this episode, and speaking with our guest authors, was really about the art itself, that still exists in New York City and elsewhere. We see these types of sculptures and monuments, and we don’t often think that this was based on a real person – at least I didn’t. I thought that, perhaps the artists would come up with the perfect ideal through their own imagination, or based on Renaissance art, or something like that. But then we learned that Audrey was a real person, and she had a real life. She had real success, and then she had real failure, and it really humanizes these iconic sculptures of Audrey, and really puts a human face on the art world itself.

Lauren: Thanks for joining us for A New York Minute in History. This podcast is a production of the New York State Museum, WAMC Northeast Public Radio and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy foundation. Our producer is Jesse King.

Devin: We’d like to thank author James bone, Diane Rozas, and Oswego County Historian Justin White for taking the time to speak with us. For more information on Audrey Munson and pictures of some of her monuments, check us out at wamcpodcasts.org.

Lauren: Next episode, we get out of the studio and search for Timbuctoo in Essex County. Until then, I’m Lauren Roberts.

Devin: And I’m Devin Lander.