On this episode of the podcast, Devin and Lauren were able to attend the unveiling of the brand-new Garnet Douglass Baltimore historical marker at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in Troy along with Bill Pomeroy himself. Garnet Douglass Baltimore was the first African American graduate of RPI and went on to a long and very successful career as a civil and landscape engineer.

Interviewees: Dr. La Tasha A. Brown, Director of Community Relations at RPI

Unveiling Ceremony Speakers: Bill Pomeroy, founder of the William G. Pomeroy Foundation and Dr. Martin A. Schmidt, President of RPI

Marker of Focus: Garnet Baltimore, Rensselaer County

Devin Lander and Lauren Roberts by the Garnet Baltimore marker. Photo courtesy of Lauren Roberts.

Garnet Douglass Baltimore. Image courtesy of the Hart Cluett Museum

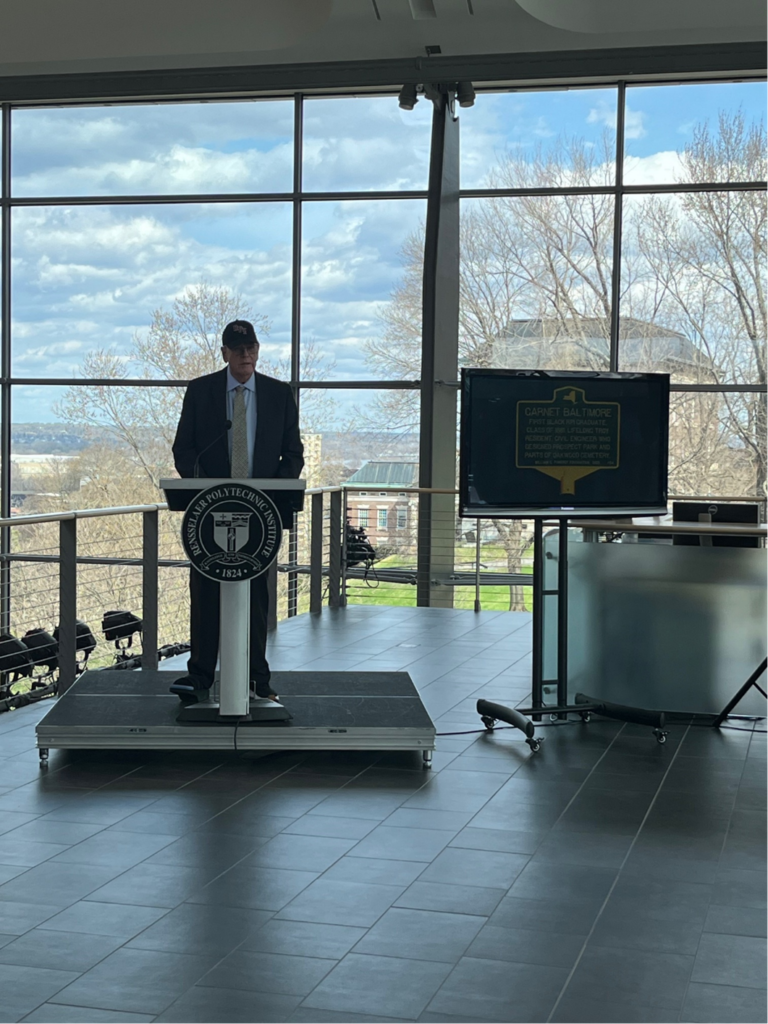

William G. Pomeroy speaking at the Garnet Douglass marker dedication, April 15, 2025. Photo courtesy of Lauren Roberts.

William G. Pomeroy speaking at the Garnet Douglass marker dedication, April 15, 2025. Photo courtesy of Lauren Roberts.

Further Reading:

Kenneth Aaron, “Troy Street Paved with Family Pride,” Albany Times Union, February 11, 2021.

“Garnet Douglass Baltimore, 1859-1946,” The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

“Garnet Douglass Baltimore,” Black Past.

Suzanne Spellen, “Garnet Douglass Baltimore: Troy’s Landscape Master,” New York Almanac.

“The History of Oakwood Cemetery,” Oakwood Cemetery.

Teacher Resources:

Hart Cluett Museum, Educator Resources

Follow Along:

Devin & Lauren

Welcome to a New York Minute in History. I’m Devin lander, the New York State historian, and I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County.

Lauren Roberts:

On this month’s episode, we’re taking you to a brand new historic marker located at one oh 5/8 Street in the city of Troy, which is part of Rensselaer County. The sign is located at the top of an elaborate granite staircase known as the approach, which connects the city of Troy to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, better known as RPI. And the text reads, Garnett, Baltimore first black RPI graduate class of 1881 lifelong Troy resident, civil engineer who designed Prospect Park and parts of Oakwood Cemetery, William G Pomeroy foundation. 2025.

Now many of our listeners who are not from the Troy area may have heard of RPI, but they probably haven’t heard the name Garnet Baltimore. So let’s start off with talking a little bit about who he was and how he came to be the first black graduate at RPI.

Devin Lander:

Well, let’s start with his name, Garnett, Douglas, Baltimore. So he was from a very prominent African American, free black family in Troy. His father, Peter was a barber and also very active in community life in the city. He was also a member of the Underground Railroad and was an abolitionist, of course, and very involved with several of the most prominent abolitionists in the state and nation at the time, including Henry Highland Garnet, who was a legendary preacher and an abolitionist based in Troy at the time, and also was associated with Frederick Douglass. So that’s where we get the name Garnet Douglas Baltimore. He’s named after Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass. And even going farther back, his grandfather, Samuel Baltimore, was born enslaved and sought his freedom as a soldier in the American Revolution. He was promised to be free if he had fought on the side of the Americans during the revolution. Unfortunately, after the war, he was denied his freedom by his master or owner at the time, and so he escaped and settled in Troy, which is how the Baltimore family came to the area. Now Garnet, Baltimore was born on Eighth Street, so not far from where the marker is, and right in front of the RPI campus, actually at 160 8th street in 1859 he was born, and he again, was born into a prominent African American family that really valued education and valued the ability of education to lift up a person and allow them to pursue a career and a life on their own.

Lauren:

Garnett studied at the William rich school and then went to Troy Academy, where he and his brother were the first black students accepted there. He had great grades, and because of the family’s connections with prominent people around Troy, he was able to gain acceptance into RPI in 1870 seven’s freshman class, and that’s how he became the first black graduate in the year 1881 which then led to an amazing career as a civil engineer, and he remained in Troy for the rest of his life.

Devin:

One of the things about Garnett that we’ve learned is that beyond being, you know, the first African American RPI engineering graduate in 1881 was the fact that his career was long and varied, and evidence suggests that he received his first job the day after getting his engineering degree from RPI. And so that started a career in which he worked on a variety of projects around the area and around the state, including parts of the Erie Canal, the Oswego Canal bridges, other types of civil engineering projects like that. Now we were fortunate to go to the unveiling ceremony for the garnet Douglas Baltimore marker. And this entire project, the work, the research that was done to apply for the marker and to receive a marker from the Pomeroy foundation. Was done by Dr Latasha Brown at RPI, and we had the opportunity to speak with her after the event.

Dr. La Tasha Brown

My name is Dr La Tasha Brown, and it’s my pleasure to be here. I have a PhD from the University of Warwick in Coventry, England, in comparative cultural studies from there, I Well, prior to that, I should say I have a master’s degree in African New World Studies from Florida International University down in Miami, Florida, which is now African and African Diaspora Studies. That changed a couple of years ago. My undergrad is from bachelor’s degree in history, minor in English, lit, from St Lawrence University in Canton, New York. So I’ve had quite a bit of experience up and down the East Coast in terms of educational development, and then I did a bit of study abroad in the Caribbean at the University of the West Indies. So throughout my career, I’ve had the privilege of learning and working across the US, the Caribbean and the UK. So I bring a particular perspective that is global to the work that I do right now at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute as the Director of Community Relations within the Office of Community Relations and Communications.

Devin:

Alright, well, let’s, let’s talk about, a little bit about Garnett Douglas, Baltimore. When did you first become aware of Garnett Douglas, Baltimore and how did that whole interest that you have start?

La Tasha:

Yes, I started at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute back in February of 2022 I was the Director of the Office of Multicultural Programs at the time, and everyone was talking about the first African American to graduate from RPI, Garnett, Douglas, Baltimore. And I’m like, Oh, okay. Neat. You know most institutions has the first African American. What year did he graduate? Most people did not know oh. And I was just like, oh. And I was just like, Okay, I need to find this out, just because it’s the first and knowing that RPI has been around for quite some time, since 1824 which we just celebrated the Bicentennial, so I really wanted to sort of position him within sort of that historical moment. And so 1824 you know, RPI is founded, and then he graduates in 1881 and I was just like, This is amazing, regardless of the fact of, you know, putting the title or the adjective of him being a trailblazer, I’m like, that is just really interesting when you’re thinking about the development of America and, you know, upstate New York, and him working in a space that is not heavily filled with African Americans, right? And so that was like the journey he was well connected. And I should say that his father was well connected. His father was part of the Underground Railroad. And so having the opportunity to be around sort of intellectuals, at the time, black and white, being around affluent people. Because, you know, Troy, New York, my understanding, was filled with billionaires, right? And so he had the opportunity to excel, but also be very much in the midst of change and creating opportunities for a lot of people, economically as well as socially. What was neat about him, and just in terms of his namesake, is that he was given the name after Reverend Highland Garnet Douglas. And so if you think about these two individuals that carry such significance within American history, you have to expect for him to be brilliant in whatever he attaches himself to. He went on to the William Ridge school for colored children in Troy. And then from there, he went to the Troy Academy, where he was there for five years with his younger brother. And then he was thinking about Harvard University. And then he decided to focus on STEM as we call it now, and apply to RPI. And so that started his journey, but thinking about physically where he was in Troy, he was right on 8th street, and so RPI was right above so every day, he was engaging with that academic space very intentionally, but also just being a passer by the education institution as it was being built out. The suspicion is that there was other African Americans, and I say other for small number, right? This is class size for 1881 was only 17. So there might have been one or two other individuals of African descent. We would know that they would be male as opposed to female, but we don’t have that definitive answer as of yet. But you know, you know more work is to be done on his life.

I wanted the marker just to sort of signify, not so much that he went to RPI, but to really mark the year, because everybody knew his name, you know, well known on campus at RPI, well known in the community, but to have that historical date that people can pass by and see constantly that was really important to have it at the approach that really came later. But with regards to the foundation and the process, I was concerned about what region I was located in, right? So when is the deadline? Because I was already going into the archives at RPI and looking at the various maps, and then going down to the, looking at their materials, looking at the materials online, but I didn’t have a sense of what was his story, and so there was a lot of conversations that I was having with people that were intimately connected to his journey, that had documented in various ways, whether it’s for political speeches, for the, you know, the various presidents, or just kind of folklore in the community.

We had a Juneteenth event back in June of 2022 and it was a localized version that was to celebrate Garnet Baltimore, and it was at that moment I was just like, this would be a really good idea to have a historical marker for him. And so I went onto the website, I missed the deadline, and then I was just like, Okay, let me get this started. What is needed in terms of the primary and secondary sources. So I started to do a deeper dive in the archives at RPI, and having conversations with Jennifer and Tammy, who were the archivists at the time. And then, you know, it was everything from his academic records to what was he involved with in school in terms of extracurricular activities, because that shaped his world view. Who else was in the class, who was on the Board of Trustees? Because all of this is being shaped by the fact that he was the first How did he get into this space, right? You know, what was the political connection to the community and the capital region at large? And then knowing that his father was an affluent person in terms of, not just, you know, financial means, but also political connection that played a role. But then I also wanted to know, did he have any writings for himself, right? And he didn’t. There was a lot of newspaper clippings that I was able to come across up and down the country of him visiting Ian. There’s quite a bit in black newspapers announcing his visit, for obvious reasons, right? And then there was just a series of committees and councils that he was a part of in terms of being part of the community and volunteering, not just with RPI and the alumni network, just but beyond that. And then I realized I needed to have his birth certificate, his death certificate, and then going down to Troy and getting those records, and then looking at the records of where exactly was his house, because that was the big challenge. Was it on the side of RPI? Did RPI, you know, do they now own that property, or is it owned by the city? Because originally it wasn’t going to be a marker just for him. Am, but it was a marker at the location of where his house was located. And then I had a lot of conversations with Christy at the Pomeroy Foundation, and she’s just like, if there’s not a stone or anything left, you can’t put the marker there. And so it was a series of brainstorming like, so what is the real sort of draw between the campus, remembering him and the community, and then you have Prospect Park, Oakwood Cemetery, and then he’s a true Trojan. And so it just seems fitting to have it at the approach, and then the history of the approach and the Rubin foundation, it just all came together

about a year later, because, again, I missed the deadline, and then you have another job, though,

I had another job, right? But to me, it was the process of utilizing the skills that I acquired, you know, as a result of getting my PhD, and then also not just looking at the race component, but like the cultural impact. How was he instrumental in creating community? And he was very much involved in community building and community change and providing access through his work as a as an engineer, and so that that was the process. And then I think it was November, the beginning and though the end of November, beginning of December, I got noticed that, you know, I was awarded the Pomeroy historical market grant, terribly excited.

And then we had to figure out what was the proper wording, and that is where the challenge comes in, because it’s a small space, and it’s not a poem, right? And so you want to be as concrete in terms of delivery of the words, but also as impactful, because you know that people are going to see this for a really a long time, and this is possibly their first touch point into doing a deeper dive, not just into gardening deep Baltimore, but Oakwood cemetery, RPI, Troy. And then it opens up a bigger space to go down a rabbit hole of just knowledge and time and space, and so it’s lovely to know that the marker is up at the approach. And that is not just an RPI experience, but it’s a community experience.

Devin:

But I’m curious about so some of the logistics stuff with all of this, I know can be complex.

With placing a marker in certain spots, was there a difficulty in placing it where it is now on the approach?

La Tasha Brown

It wasn’t smooth sailing. It was a process, for sure. It’s figuring out the foot traffic, right? Yeah. Logistics is, you know, who’s gonna see this, you know, are we just looking at it from the standpoint of vehicles passing by? Are they gonna actually slow down? Not too long ago, RPI put in a crosswalk, and so that was the perfect locations you would, you know, travel up or down the approach, but more so traveling up the approach, and where the mark is located is right at the crosswalk, so you have to press the button and wait, and as you’re waiting, you’re now reading.

And so that allows for not just the individuals that’s standing at the cross walk to cross the street, but it also allows for the vehicle, the person’s in the vehicle to then look at the marker themselves, because it’s big enough for you to take a peek. And if you’re really curious, you can pull over and park safely and get out and read the marker.

Lauren:

One of the attendees at the unveiling ceremony for the Garnett Baltimore marker was Bill Pomeroy, who is the founder of the William G Pomeroy Foundation, and also a graduate of RPI from the class of 1966. He was invited to give remarks about the Garnett Baltimore marker located at his alma mater.

Bill Pomeroy:

Thank you, folks, and I’m excited to be here today to celebrate the life and the legacy of Garnet Douglas Baltimore, an accomplished engineer, landscape designer and RPI first graduate. We’re marking that legacy literally with this new historic marker funded by the foundation I started 20 some years ago. That foundation, like many, many meaningful things came from a deeply personal place. My time at RPI from 1962 to 1966 taught me a lot about perseverance, problem solving and purpose, but it was a unexpected leukemia diagnosis, AML, that gave me clarity on how I wanted to give back. With the odds stacked against me, I set out to create something that could help others. Long after I was gone, I focused first on expanding the bone marrow registry, especially for underrepresented communities. The goal give more patients like me a shot at a life saving donor match, and I’m proud to say that our work has helped facilitate over 300 bone marrow transplants.

Thank you very much. Later, my interest in history took hold, and our Foundation began helping communities across the country uncover and celebrate their local histories. As a boy, my dad took me on his sales calls and frequently stopped at historic sites to learn more about them, and I guess that’s where the bug got planted in my head. And I continue now with markers.

So when I learned that someone had proposed a marker for Garnett, Baltimore and on the approach, no less, you know the one I remember as an ankle breaker from 1962, I was thrilled. It’s a perfect spot. And thank you, Dr Brown for thoroughly documenting the facts for the marker and the back story. Baltimore lived his whole life right here in Troy, likely right down here, close to where the marker is today. The approach physically and symbolically connects the city of Troy to RPI. What better place to celebrate someone who embodied both and Garnet Baltimore is not just celebrated here, his influence, you know, really goes further than here. He helped design Oakwood Cemetery. His grandfather, Samuel Baltimore, a revolutionary war Patriot is buried in Troy’s Mount Ida cemetery. Garnet likely became aware from family lore of patriots buried in both places, and we’re currently developing a new marker with the sons of the American Revolution to honor 22 known patriots interned at Oakwood.

We’re also working on a marker for Mud Lock on the Oswego canal, where Baltimore oversaw a challenging expansion project in the mud. He’ll be recognized by name when that marker is installed later on this year.

All of this makes me especially proud to now see a marker here that ties him firmly and forever to RPI and the city of Troy. This marker will spark curiosities and passers by, pride in the community and the inspiration of future generations who, like Baltimore, use their talents to make a lasting impact as someone who shares his own whose own story was shaped by this place. It’s an honor to share in this moment of pride for your community, and I want to thank you for the opportunity.

Devin:

You now, much like one of his family’s friends, Frederick Douglass, who, for his second marriage, married a white woman, Garnet Douglas Baltimore also married a white woman named Mary Lane, who he met doing a job on Long Island. Her family originated from Long Island, but they moved back to Troy to help further his career and keep his career going. And she was a strong advocate, not only for equality for African American people, but also for women. She was known as a suffragist, and when we spoke to Dr Brown, she talked about how she was able to track down Mary Lane’s family and actually have representation from that family at the unveiling event.

La Tasha Brown:

I reached out back in I want to say it was 2016 if you look on the archival website for RPI, there was a thread of discussions that were going on, and there was a woman, she said that she was a descendant of Garnet Baltimore, like a great, great grandniece. And so I did a deep dive and Googling and putting in her name in various websites and forums, and then even sending a follow up to that thread.

I presume she’s still alive. She’s about 66 and I’ve called three different four different emails were available. I presume that they are still members of the family that are alive, but I don’t have exact evidence to prove that, obviously, with the Mary Lane family, they were here yesterday, and that is the Charles Marder, who is the nephew, the great, great, great grand nephew of Mary lane. And I found him through having conversations with several people, and then coming across his mother’s announcement of her death, yes. And so I read that, and then they had a listing of him, along with his children and his, you know, extended family members. And then I did a deeper dive on a Sunday afternoon. I would never, you know, forget that I’m sending out emails, looking at LinkedIn profiles websites and reading additional articles. So I got in contact with several of individuals via email, and then I was hoping that somebody was going to reply back, but I didn’t know how it was going to be received, right, right? Right? And so few emails bounced back, saying that their mailboxes were full. And I was just like, all and then then one came, I want to say, maybe two weeks later.

And so he replied back. And just like, this is really interesting. I’m like, indeed is interesting. And then he was telling me that he went to Bennington, Bennington College, okay? And Vermont, so he used to pass through the area right to go back down to Long Island, okay? And so he was familiar, um, within reason, yeah, of RPI. Well, he knew RPI, but the area. And then he paused a bit, and then he reached out to the local librarian, archivist, and they did a little bit of research, and then they came back and just like, let’s talk a little bit more. And so I met Charles maybe three weeks ago, two and a half weeks ago, via WebEx, and we had our discussion, and sort of finalizing the details of this event, and talking about RPI and Mary Lane and what information is available. And then I reached out further to the librarian down on Long Island, and again, there is no primary information from them, right? Everything else is just secondary. And so I was taking these, these puzzle pieces, and putting them together, and they weren’t aware that she left. So they were being introduced to her and to Garnet Douglas Baltimore yesterday. But clearly they did a little bit of research prior to our event, my event yesterday, but this was their introduction to that side of their family.

Charles Marder:

Thank you, Dr Brown, I really appreciate it. If it weren’t for you, we wouldn’t be here. You literally dug us up, or rather, figuratively dug us up. I will be careful when I say here, talk about cemeteries, but thank you.

That’s I’m here. You know why I’m here, but I don’t know, or you know how I’m here, but why I’m so excited to be here is because I am a landscape design, horticultural person that been doing for 50 years with my wife and later on, my son, Silas, who’s right over here. It took him a little while,

but he’s come a long way. And I’ve also worked on Prospect Park in Brooklyn Central Park in New York City, museum decommissioning Philip Johnson’s Museum of Modern Art about 10 years ago, when they renovated the place, took them out to the Botanical Garden. I’ve decommissioned Linden circle and the botanical garden. I have built some things. I’m not just a decommissioner, but believe me, we moved giant trees. We moved one today to Connecticut with a police escort. It was a valuable tree,

but so anyway, I have a certain sympathy or empathy, when I found out about my aunt’s great my great, great great aunt’s husband and so proud that he was part of the family.

Lauren:

Two of the major projects that Garnett worked on in Troy was the laying out of Prospect Park and also laying out parts of Oakwood Cemetery, which is a beautiful cemetery that Troy is well known for as part of the unveiling ceremony, attendees were treated to a tour of Oakwood Cemetery, which included mentions of several prominent people that were buried there, but also a tour through the areas that Garnet laid out, and also a stop at his grave and that of the grave of his wife, where there was a wreath laying ceremony and a local pastor gave some moving remarks about the legacy of Garnett Baltimore. In addition, we stopped back at the chapel, and on display were maps from the early 1900s that Garnet Baltimore had actually laid out and signed. His original signature was on the maps, so it was a real treat to be able to see his actual presence in the cemetery on these maps as part of their archives.

Devin:

We’ve talked on this episode about how Garnet Douglas Baltimore was a trailblazer, first African American civil engineer, graduate of RPI, first graduate from other schools in the area, and also a very active and prominent Civil Engineer for his whole career, working on projects around the state and around the area. But he really was a Trojan. He was a proud resident of Troy, New York. He was very active, along with his wife, Mary Lane, in local community events and community works beyond his career, as I noted, Garnett was born on Eighth Street and Troy, and in fact, he died in the exact same house he was born in. He died in 1946 he was 87 years old, and he was active as an engineer right up until the end of his life. So the location of the marker could not be better. It’s located on Eighth Street, as we said, which has also been renamed Garnett Douglas, Baltimore Street in Troy. And it’s on the approach, which is this arched concrete walkway and stairs that connects RPI campus to the city of Troy, crosses Eighth Street and goes down the hill into the city itself. And no better place could have been picked to honor the legacy of Garnett Douglas Baltimore, who was himself, a connection between the Institute and the city RPI, President Martin Schmidt reflected on this connection at the unveiling ceremony.

Martin Schmidt:

It’s a real pleasure to be here. We’re gathering, of course, to unveil a significant tribute, a New York state historical marker dedicated to the pioneering spirit and lasting impact of Garnet Douglas Baltimore, and it’s made possible by the William G Pomeroy Foundation, and I’m deeply grateful that they’re present with us today. Wonderful to see fellow alumnus, Bill Pomeroy, and just delightful. It’s also special that this marker will be placed at the approach, which is a site that’s deeply embedded in the history of both Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, but also the city of Troy. It’s our gateway between the campus and the town.

And to that note, before I continue, I want to extend my deepest gratitude to Mayor Carmela Mantello for joining us today, we’re delighted with the partnership that we have with the city on so many fronts and her continued dedication to preserving and celebrating the rich history of Troy is really inspiring. So thank you. I also want to take a moment to recognize and thank the members of the extended family of Gardner, Baltimore’s wife, Mary Lane, who are here with us today. Your presence is a meaningful reminder of the lasting connections between history, family and community.

Additionally, just thanks again for to the Foundation for their incredible work in recognizing and commemorating historic figures who have shaped our community. Their mission ensures that we never forget the contributions of individuals like Garnett, Baltimore who helped lay the foundation, both literally and figuratively, of the places we call home, Garnet Douglas, Baltimore was not just a trailblazer. He was a visionary. As the first black graduate of RPI in 1881 I hadn’t realized it was 100 years before I got to graduate from RPI. He forged a path in civil engineering that would leave a lasting mark on this city and beyond. His work, particularly his contributions to the design and preservation of Oakwood Cemetery remains an enduring testament to his expertise and deep connections to Troy, the city where he was born and spent his life. Baltimore’s legacy as a civil engineer, landscape designer and lifelong Troy resident is a reminder of the importance of recognizing those whose work continues to shape our communities for generations. Here at RPI, we take great pride in our long and storied history of innovation and leadership in engineering science and technology, but our mission extends beyond technical achievements. We seek to make an impact in the communities we serve. Garnet, Baltimore embodied this principle, bringing his technical expertise with a profound sense of civic responsibility and the approach. The approach is a historic landmark that connects our campus with the city, and so in placing the plaque at the top of the approach, we’re recognizing the bridge Baltimore created between engineering excellence and community development. This unveiling is not just about marking history. It is about learning from it. It is an opportunity for individuals of all ages to explore and appreciate the contributions of those who came before us. I hope this historic marker serves as an enduring symbol of Baltimore’s remarkable achievements and inspire future generations of engineers, leaders and innovators to follow in his footsteps.

Devin:

Now Garnett was such a prominent resident of Troy that when he passed away in 1946 the Troy record, which is the local newspaper, ran a front page obituary with a photograph, and they said, quote, There was a time when he was in the thick of Municipal Affairs. He was architectural engineer at Oakwood Cemetery. He laid out Prospect Park. He was probably the greatest surveyor in the city’s history. He was as much a part of Troy as the monument.

La Tasha Brown:

With Garnet D Baltimore, there is so much to still uncover about his life and providing a holistic view of who he was, I think at the moment, is very fragmented. I mean, we’re getting better at looking at or positioning these puzzle pieces together, but there’s just so much that can be discovered and sort of put out there for public consumption. And I think when you think about curriculum, local curriculum, and I know that you’re, you know, part of that space that becomes really important when we’re thinking about how young people, particularly K through 12, but specifically K through eight, can feel a connection to their lives and learning environment. And this is one example that they can say he was a trailblazer. He wasn’t a trailblazer in terms of being at the forefront, and, you know, of various movements or economic development in terms of benchmarking at different periods in time, but he was at the forefront of creating change and creating community. And we always need community. So I think this would be really important to put into the curriculum on a regular basis. That sort of feeds into opening up the space of thinking about STEM and STEAM for younger individuals, particularly those of African descent. But all students.