In honor of Black History Month, this episode tells the story of the 1839 La Amistad Rebellion, in which 53 illegally enslaved Africans rose up against their Spanish captors off the coast of Cuba, took over the ship, and attempted to sail it to freedom. They eventually reached Long Island, where they were arrested by U.S. officials. Aided by New York abolitionists, the Amistad Africans fought various legal battles for over two years before the Supreme Court finally ruled in their favor in what was one of the most important court cases related to slavery before the Civil War.

Marker of Focus: Schooner “Amistad”, Suffolk County

Guests:

Dr. Marcus Rediker, author of The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom and producer of the film Ghosts of Amistad: In the Footsteps of the Rebels, and Dr. Georgette Grier-Key, Executive Director and Chief Curator of the Eastville Community Historical Society.

A New York Minute in History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio and the New York State Museum, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Elizabeth Urbanczyk. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Marcus Rediker, The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom, 2012.

Howard Jones, Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy, 1997.

Alexs Pate, Amistad,1997.

Teaching Resources:

Consider the Source New York Slavery Resources—New York State Archives Partnership Trust

Ghosts of Amistad: In the Footsteps of the Rebels Educator Resources

Discovering Amistad Teacher Resources

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York State historian.

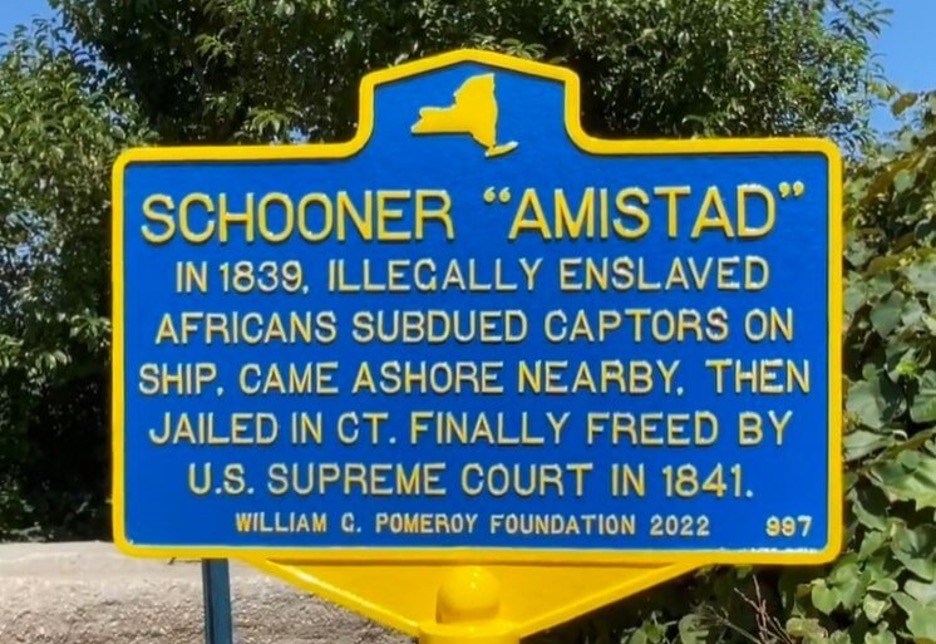

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. In honor of Black History Month, on this episode, we are heading out to Long Island. The marker of focus is located very close to the shore, near 185 Soundview Drive in Montauk. The title is Schooner “Amistad” and the text reads: In 1839, illegally enslaved Africans subdued captors on ship, came ashore nearby, then jailed in CT. Finally freed by U.S. Supreme Court in 1841. William G Pomeroy Foundation 2022.

The story of the Amistad may be familiar to many of our listeners, because in the late 1990s, Steven Spielberg produced a major motion picture, which followed this story. And the story is of a ship that was carrying illegally enslaved Africans heading to a plantation in Cuba. These Africans rose up and revolted successfully against their white captors, and attempted to sail the ship back to Africa.

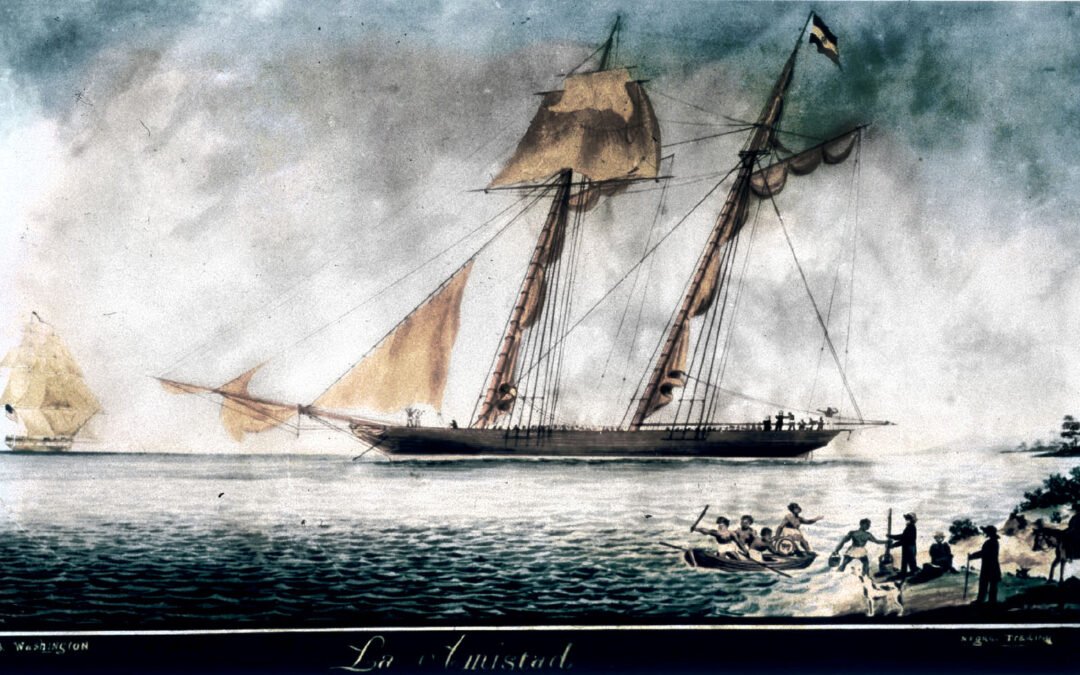

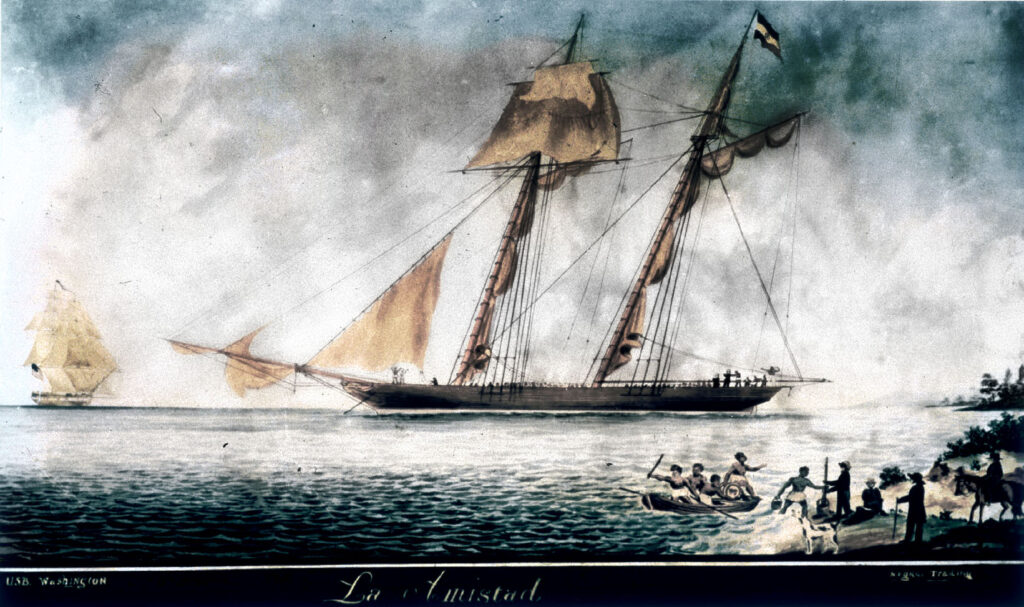

Devin: The Amistad case is interesting in a lot of ways, we have to realize that in 1839, and the era in which they were stolen from their homes in Sierra Leone, which was a British territory, the slave trade had been made illegal by the British, but there were still slavers bringing enslaved Africans across the Middle Passage to the United States, to the colonies in the Caribbean. So that was very much still happening. In the case of the Amistad – which itself was not a slave ship, it was a schooner – it was transporting 49 enslaved men and four children from one part of Cuba to the other. These men and these children had been purchased by two plantation owners.

So, in Spain and Spanish colonies at this time, slavery was still legal. So again, you have this complexity of violating British rules and laws, as far as the slave trade from their territories is concerned, we have the same complexity in the United States at this time: in southern states, slavery is very legal in many northern states, but at all, it’s illegal. So this is a very complex case. The idea that this was a successful revolt at sea is something that we spoke to Dr. Marcus Rediker about.

Dr. Marcus Rediker: My name is Marcus Rediker. I am a distinguished professor of Atlantic history at the University of Pittsburgh. I have written a number of books, all of which have something very important in common: they are all what we call “history from below.” The history of ordinary people making history.

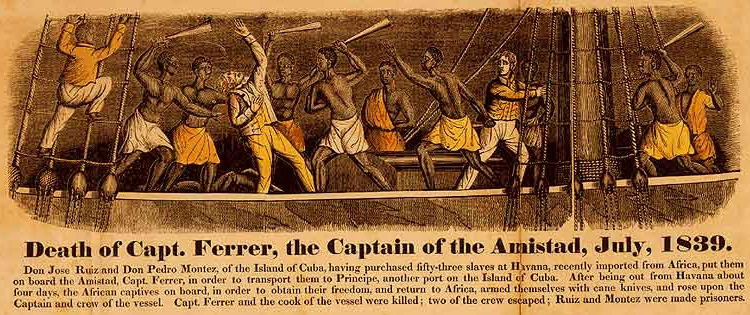

As I was writing a previous book called The Slave Ship: A Human History – seeing one revolt after another fail – in the back of my mind, I’m thinking, “Why was the Amistad rebellion successful?” What I wanted to know is: who were these people who made it? How did they actually do it? The main finding on this set of questions was that these people were from southern Sierra Leone, all 53 of them. They were from about nine or ten different ethnic groups. But they came from a region in which the wars of the slave trade were raging. And what this meant was that the men of every village had to be trained warriors. So what I learned was that the ways of warfare in southern Sierra Leone, were the key to the successful uprising. So in my view, the most important thing about the Amistad Rebellion has its origins in West Africa.

Steven Spielberg’s film begins with Cinque trying to get a nail out of a piece of wood, which he can then use to pick the lock. There are actually sources that say that they broke the padlock, not picked it that they broke it. And it was crucial for me to figure out that there was not one, but two blacksmiths on board. And metallurgy in this part of West Africa was quite advanced in this period, I’m quite confident that these people knew the properties of this metal, and they knew how to break it.

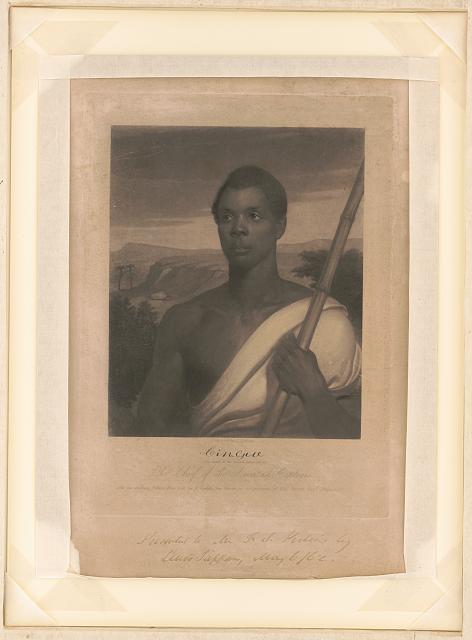

One of the principles I might say, of the kind of history I do, is that we treat ordinary working people as thinkers. So one of the things that I’m trying to figure out is, what kinds of things would the Amistad Africans have known that would have helped them to conceive, to plan, to coordinate, and to execute this uprising on board the ship? I found that one of the keys was: all of the nine or ten ethnic groups came from areas of southern Sierra Leone where a key institution of what is called the Poro society; all male, secret society that is involved in the governance of the village. But one of the things that’s really important about the Poro society is that it makes the decision about when to go to war. And it turns out, I found a document, a really remarkable document; some years after the Amistad rebellion, when – after people had gone back to Sierra Leone – one of the Amistad Africans described the process of making that decision. And he said there was a big debate. And some people, led by Cinque, who, by the way, had quite serious military experience, he was on the side of the uprising, but other people were reluctant. And so basically, this person said that a speech that Cinque made, convinced people, they decided by consensus that they were going to try to rise up and capture the ship.

Now, something else happened that made them believe that this was possible. You know, there were four children on the Amistad, the three little girls, and little boy, they were not in chains. And so they had the freedom to sort of move about the ship. And the little girls discovered a box that had cane knives in it. But it turns out that the Mende warrior fought with a cutlass, or a long knife of this kind. So imagine yourself as a Mende warrior when you find out there are all these weapons that you can use, that you’re familiar with. This is like a sign from the gods that you are meant to rise up. So again, there’s a military knowledge and skill that’s involved in this.

Okay, so when they did finally break onto the main deck of the Amistad, the crew are starting to fight back but two sailors who were supposed to defend the ship and this situation saw that they weren’t going to win, and they threw a canoe overboard and jumped overboard to follow it. And in a matter of five minutes, the Amistad Africans had captured the ship. So they took the two enslavers on board, Ruiz and Montez, and made them their captives, and told them to sail the ship in the direction of the rising sun, sending an eastward back towards Sierra Leone. But Montez, who had been a ship captain, was very clever. And he didn’t do that. He pretended to sail in that direction during the day, but at night, he sailed back toward the coast in the hope that they would be captured. With the help of the Gulf Stream, going up the Eastern American coast, they go past Fire Island, and they go up to the northern end of Long Island, a place called Culloden Point, and they decide to go ashore and they see a group of white hunters. Now one of the members of the Amistad group could speak a little bit of English, his name was Burna. They went ashore, carrying their muskets. They put their guns down, they raised their hands they said, “We mean you no harm.”

There’s one fascinating thing that this man Burna said, when he saw these hunters he asked them: “Is this slavery country?” Now, to me, that’s a fascinating point because it implies the knowledge that some areas were slavery country and other areas were not. And as it happened, New York State had abolished slavery in 1827. And so the men said, “No, it’s not slavery country.” And then the Amistad Africans began to rejoice and dance, and so great was their joy at having reached a place that wasn’t slavery country. This is a crucial part of the story: It turns out that Montez, the enslaver, had planned to take them ashore in Charleston, what do you think would have been the outcome there? So the fact that they did make it that far north is actually a crucial part of their eventual success. But before they can communicate very much with these white hunters coming into view in the background is the U.S. brig Washington of the U.S. Navy. And the Amistad men see this, and they go rushing back to shore, but they’re too late. And so they’re captured by the U.S. Navy, their vessel is towed across to New London, Connecticut, where they’re put in jail. And thus begins the sort of landed part of the story.

Lauren: You mentioned the complexity of the different countries having some places that had banned the slave trade and some that had not. Another complexity is salvage rights. We’re dealing with a schooner that has been taken over. So when the brig Washington gets on board, they have a decision to make once they discover that it is a number of illegally kidnapped Africans, of course, they don’t know that. They believe that they are enslaved Africans, which means that they would be treated as cargo. And so along with the boxes of saddles, and cloth and other things, enslaved Africans are considered to have a monetary value as part of that cargo. So the captain of the brig, Washington decides that he would probably have a better chance bringing that ship into Connecticut to claim salvage rights, because Connecticut did not fully abolish slavery until 1848. So the ship gets brought into Connecticut, and that’s where the Africans are imprisoned, and that’s where the court cases begin.

Devin: The president at the time was a New Yorker, Martin Van Buren, and he was more inclined to essentially just give the enslaved Africans back to the plantation owners, give them back the boat, send them on their way and kind of move on. But the abolitionist movement who were really gaining prominence in the North of this time in New York and other northern states really saw this whole situation as an opportunity, potentially, in their wildest dreams free these enslaved people, but really strike a blow against the entire institution of slavery in this country.

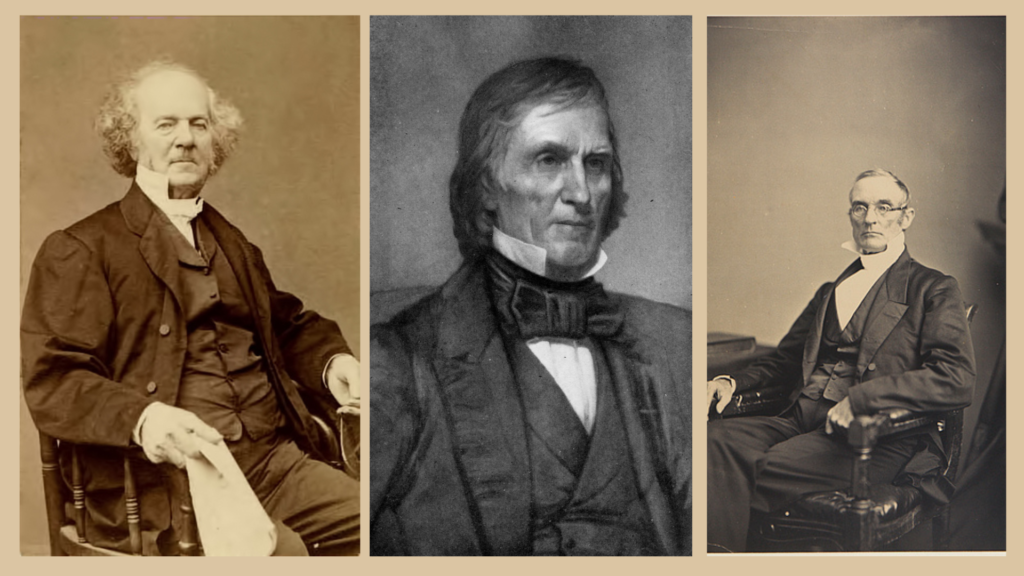

Dr Marcus Rediker: New York actually plays a very important part in the Amistad rebellion. First of all, Louis Tappan – who is probably the wealthiest abolitionist of the time – Lewis Tappan took an immediate interest in this case and devoted considerable resources to it. Joshua Leavitt, the publisher of The Emancipator was based in New York, which was one of the main ways that the story became known. They rushed to New London to meet the Amistad Africans.

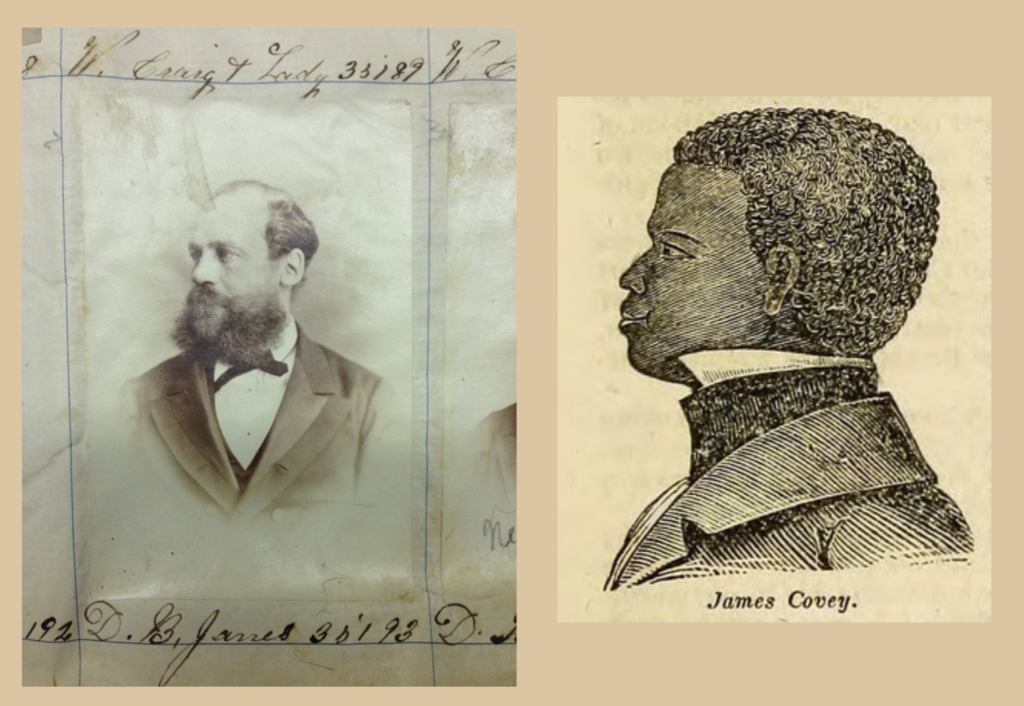

And that was because a rank and file abolitionist named Dwight Janes, dockside grocer, had gone on board the Amistad as soon as it came to New London, and then went and wrote letters to Tappan and all the rest, saying, look, we’ve got an unbelievable opportunity here for the abolitionist movement. But here’s another example of the way New York mattered, the Amistad Africans spoke many different languages, but the abolitionists could not find people to communicate with them. They brought in people from three or four different ethnic groups – African ethnic groups – to see if they could speak any of the languages that the Amistad Africans could, and none of them could. So this Yale professor Josiah Gibbs, but he talked with a little girls, and they taught him to count to ten in Mende. So what did Gibbs do? He went to the waterfront of New York and walked up and down the docks, counting from one to ten in Mende to see if anybody could understand him. But these two sailors came up to him and said, “We’re Mende.” One of these was James Covey, who will end up being the main translator, who then goes immediately to the Connecticut jail. And that then allows the Amistad Africans to tell their story to the world. Before that they were, they were like an abstraction to everybody. Nobody really knew who they were, The motley crew, on the docks of New York is what made possible the breakthrough in communication.

The first thing your listeners need to know is that a jail in the first half of the 19th century is not like a jail today, they were much more open institutions. The jailer would always try to make money on the people who are in the jail. So imagine the jailers’ excitement when there’s this huge interest in the Amistad Africans, and people start lining up to come and walk through the jail and see them, you know, talk to them through the interpreter after James Covey is found. And so he actually – the jailer – starts charging admission. The abolitionists don’t like this. But the Amistad Africans seem to have liked it because people brought them food, people gave them money. And then the other thing that happens: artists came in, these artists would, you know, one guy created a panorama of the revolt, someone else created a history of the Amistad Africans and drew portraits of quite a few of them. And so this actually helped to fuel the abolitionist cause by making them real to people.

And see, that they couldn’t really be mistreated very much, because the abolitionists were in there. So they’re – everything is closely watched. At times, they would be allowed to go out on New Haven common, where they would perform these amazing feats of acrobatics. And what I learned was that military agility and acrobatics was part of the training of a Mende warrior. So there was kind of a popular entertainment aspect to all this. But what’s really crucial is that many people who filed through the jail would go home and write a letter to their local newspaper. And they built – through this through this contact – a really strong following of supporters in New Haven, some of whom were abolitionists, but some of whom were not. I mean, I saw letters of contribution to the Amistad committee, and people will say things like, “I am no crazy abolitionist, but I do support the right of these people to be free.” There was a kind of social movement aspect of this, they had really, you know, most of the most white people in Connecticut, in this period, didn’t know any people from Africa. So what happened was, I think they became real, they became human beings, just like you.

Devin: So this was a, as we noted, a very complex court case, it took over two years for it to finally there to be a verdict started out in the courts of Connecticut, the courts there decided that this was a federal problem. And so they kicked it upstairs to the Supreme Court. And as we noted, the abolitionists had hired a team of attorneys to really work this case at the local level, and they were successful in petitioning it to make it to the Supreme Court, but they needed a kind of star to really bring this case forward. They chose a former president, by the name of John Quincy Adams, who at the time, was actually serving in the House of Representatives, but he was also – he was elderly at the time, he was 73 years old, but he was exactly what they needed. He was a big name, a person who had impeccable legal credentials. And what he does is study the case, he studies all of the legal documents, and he argues for eight and a half hours in front of the Supreme Court, and in the end, it sways the court in the favor of the enslaved Africans.

Lauren: Although the two year long court saga takes place in Connecticut, we need to remember that the story actually begins in New York. So we spoke with Dr. Georgette Grier-Key to learn more about the impact that the Amistad story continues to have on New York state history.

Dr. Georgette Grier-Key: Hello, everyone, my name is Georgette Grier-Key, and I’m the executive director at Eastville Community Historical Society, which is my home base, among other positions that I hold throughout the state. Eastville is situated in Sag Harbor, and we’re sandwiched in two townships, the town of East Hampton and the town of Southampton. And so what we have been doing since 1981, we were incorporated by the Board of Regents to tell the history of Sag harbor in the East End. And our tagline is “Linking Three Cultures”, because we have a population of indigenous that settled from Montauk, when they were pushed out. We also have African Americans that were both free and enslaved, then we have the immigrant population of European descent that settled there. So as you can imagine, our history is very vast, from colonial times to the present. And we’re making sure that we continue to tell that history through preservation, through the arts, and looking at humanities and how they matter for our life today.

This is a global story, the Amistad – and even a national story, because this case, it went all the way to the Supreme Court. And you have John Quincy Adams defending 35 enslaved Africans. So yes, it is a story about enslavement. But it’s a story also about resilience. It’s also a story about their culture, I think about how they were trying to navigate back to freedom by using the stars, you know, that’s another extraordinary story. So even this is the precursor to the Underground Railroad. And you start to think about Harriet Tubman, how she used the stars. But I think it’s more important because when we talk about slavery, the North has gotten a pass because it has been written out of history. And so this is a nod to Northern slavery that we often don’t talk about, but it’s happened right here in Montauk, they came aground here, they were looking for provision here. And for my organization, along with the Montauk Historical Society, and other local groups, we have sought to preserve and reclaim this history in its specific place where it happens, this new marker from the Pomeroy foundation, it’s actually closer to the spot where it happened on the beach, which is really not accessible for a lot of people. You know, it’s back and off the beaten path. And so that was a day to remember. And so we can talk about that day, too.

We wanted to commemorate it at the right time, if you look at Amistad, we did it on the actual day, which is August 28. So we said this has got to be a big deal, we need to make a big deal out of this. So we went to planning. And when we went to planning, we came up with a program, I gotta tell you, most people who attended that day thought it was very, very spiritual. Because we had various things like we had Dr. Maria DeLongoria, do a libation celebration to pour out and to pay homage to the ancestors, right. So that was very powerful. Then we had a young group called the Venettes, two young men come and do a dance at the site on the beach. And then we had something that’s historically called a ring shout, it’s not really a dance, it’s more of a cultural, spiritual type of thing, so we had that. we had African drumming, we also had an African instrument called the kora. So it was a very powerful day where there was celebration, but also remembrance, and a means to move forward with telling this truth and this history and what it means for our region.

And then at the end, we go back up to the spot, because we were down on the beach, I gotta tell you this, walking from the actual spot down to the beach, you could swear that you were like, in the jungles of Africa, like taking that same journey walking through the woods, to go to this water, this beach. Because if you understand where the topography of this area and the terrain, it’s really very difficult to navigate. And we had everything set up there. But walking through those woods, you couldn’t see anything. But you could hear the African drumming. And we did that intentionally because we wanted people to understand that there’s a change happening right now. And so that’s why I say it started off very powerful in the beginning. So how do you top that? I gotta tell you, if you see the video, you’ll say, “Oh, my goodness!”

And so this year, we’re like, we got to do something, again, because we’ve been trying to make this an annual thing. And so we call it Amistad Weekend. This year, we will be having Discovery Amistad back. And we’re looking at dates of August 22 to August 29. And so we will have tours, we will be on the beach where they actually ran aground. So we’re planning a whole weekend, again, to really talk about this history.

Lauren: I think it’s really cool the way that the community has used African culture to celebrate the unveiling of the marker but then to talk about the cultural influence both in 1839, and today. When the Africans who were on the ship were held captive, they were using their experience as African warriors, first of all, to be able to revolt successfully. And then they continue to use their skills and their culture, while they are trying to earn money to get themselves back to Africa. And to be able to push that forward into today, in the way that the community was using African drumming, and, and dance and commemoration. It’s really inspiring to have this type of marker unveiling as the result of, you know, getting a grant from the Pomeroy Foundation to be able to reclaim this history, bring it back to New York, right near the area where it happened. And to evoke feelings about the influence of that culture on this story.

Devin: You’re right, and it does tie directly to the work of Marcus Rediker who, in his book, The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Rebellion really tries to answer the question of, you know, why was this revolt successful? So it’s really an amazing story. And it’s a story about the human desire for freedom, I think, but it’s also a story that is uniquely an African story. And that’s why, as you said, the bringing together today, at the unveiling of the marker in 2023, African culture and music and all of that to the forefront really positions this as an African story by way of New York.

Dr. Marcus Rediker: One of the things that has always struck me about the Amistad rebellion is that: these 53 people stage an uprising on a small schooner on the north coast of Cuba, seize their freedom, guide the ship to Northern Long Island, and inside of two years, the most powerful people in the world are debating what they’ve done. Presidents, monarchs, the British Parliament, abolitionist groups all around the Atlantic, Supreme Court justices, these are the most powerful people in the world talking about this event. And to me, this is one of the really great things about history from below, you never know, when something might arise, that will create a kind of an extraordinary set of consequences. And I do think the Amistad rebellion is important because it was a victory. And even though they were not enslaved in the United States – that’s one of the reasons the Supreme Court was able to rule the way it did; it ruled on the very narrow grounds of the violation of a treaty between Britain and Spain, so as not to set any precedent for anybody who’s, you know, gaining freedom in the United States. But you couldn’t separate out the fact that you had these self-emancipated people who had taken on, you know, not just one but two of the main, you know, governments in the world, Spain in the United States and had won their freedom through this long struggle. It’s just an extraordinary story. And I can tell you, the abolitionists were shocked. They did not expect to win. When the Supreme Court ruled in their favor. They were bowled over but such as the nature of the campaign that they and these African rebels waged, it was a winning campaign.