On this episode, Devin and Lauren tell the story of the Florence Farming and Lumber Association, a settlement of free African Americans in Oneida County beginning in 1846. The Association was the creation of abolitionists Gerrit Smith and Stephen Myers, and it developed on land given by Smith, who at the time was New York’s largest landowner. The original idea for the settlement was to allow African American men to meet the threshold of owning at least $250 worth of property before they would have been allowed to vote, a restriction imposed upon them at the time by the New York state legislature. It was also seen as an opportunity to provide these men and their families the opportunity for self-sufficiency in a rural location.

Marker of Focus: Florence, Oneida, Oneida County

Guests: Jessica Harney, Camden High School social studies teacher; Rebecca McLain, executive director of the Oneida County History Center; and Matt Kirk, principle investigator at Hartgen Archeological Associates

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

“New Historical Marker Planned at Site Oneida Abolitionist Bought for Black Families to Own,” Edward Harris, Observer-Dispatch, April 14, 2023.

From Slavery to a Bishopric, or, The Life of Bishop Walter Hawkins of the British Methodist Episcopal Church Canada, S.J. Celestine Edwards, 1891. Bishop Hawkins was one of the residents of the Florence Farming and Lumber Association before moving to Canada.

Practical Dreamer: Gerrit Smith and the Crusade for Social Reform, Norman K. Dann, 2009.

Information about Stephen Myers: https://www.albany.edu/arce/MyersXX.html

Teaching Resources:

Consider the Source New York: Finding Florence

Columbia University Mapping the African American Past

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

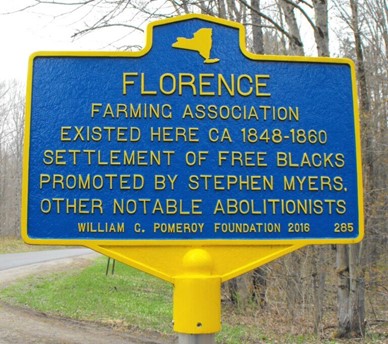

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. Today we’re focusing on a marker located on Florence Hill Road in the town of Florence in Oneida County, which is in the central part of New York state. And the text reads: “Florence Farming Association existed here circa 1848-1860. Settlement of free Blacks promoted by Stephen Myers, other notable abolitionists. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2016.”

Now, the Florence Farming Association was a community of free Blacks established in the 1840s. And it may sound familiar to some of our listeners, who remember our episode on Timbuctoo up in Essex County. They are related in that they come out of the same idea from Gerrit Smith, about enabling African Americans to own land in the hopes that they would then be able to vote in New York state.

Devin: Absolutely. The Timbuctoo episode that we did a couple years ago was something that I think some people knew about, because John Brown was associated with Timbuctoo. Less people, certainly, know about the Florence Farming Association. But for a little bit of background about why Gerrit Smith and these abolitionists came up with this idea to give away land, let’s revisit what we discussed with author Amy Godine, during the Timbuctoo episode.

Amy: It really starts, in my view, around 1821 or so, when the New York state Assembly enacted a law which deprived Black, free New Yorkers of the right to vote unless they could prove they owned $250 worth of real property. It was racialized voter suppression, with the intent of tamping down the possibility of an anti-slavery voting block that could vote against slavery’s business interests, and it was very effective. This law would effectively disenfranchise Black New Yorkers really until 1870. It wasn’t stripped from the books, and then only by federal law, not by state law. So, this law was despised by progressives, by Black New Yorkers, by white abolitionists, and all reformers, and they had tried again and again to work up a way to take it down to get it retracted. And in 1846, at the next constitutional convention for New York, an opportunity arose to address this again. And Gerrit Smith, the radical abolitionist reformer, who was also incredibly wealthy and land rich, maybe anticipated that this vote would not go the way he and other reformers hoped. And so, he came up with an idea to give away his own land in mostly 40-acre parcels to as many as 3,000 Black New Yorkers all over the state, but mostly in New York City, to help them meet this voting requirement. Not that the deeds equaled $250 – but if they moved to the land and improved the land and approved their lots, they would gain this value soon enough. So, it was his hope that in giving away land he didn’t want to people who he felt needed to get out of cities, which were mob-ridden and intransigently racist and unfriendly to Black advancement – he would be striking a blow on so many fronts.

Devin: One of the prominent abolitionists that Gerrit Smith worked with to help promote his plan, but also who he gave land to, was Stephen Myers, who was a very prominent abolitionist and African American – a former enslaved man himself who was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and who lived in Albany. He was also the publisher of several abolitionist newspapers and magazines, and became a prominent speaker in different places around the Northeast about abolition. Again, for longtime listeners to our program, you will recognize the name Stephen Myers, because in January 2020, we actually toured the Myers residence in Albany, which was a station on the Underground Railroad during the 19th Century. And at the Myers’ residence, we spoke to Paul and Mary Liz Stewart, who are experts on the Myers.

Mary Liz: When vigilance committee members met in the front parlor of the Stephen and Harriet Myers residence, one of the things that was a real eye opener for us – I mean, we assumed that as abolitionists, their first task would be to strategize on how to abolish the institution of slavery and what kind of strategies they would engage in to do that. Then, of course, there was the understandable issue of how to meet the needs of freedom seekers coming into town and coming through the front door of the Myers’ residence. So certainly, those would be at the top of their agendas. But as we continued our research, what also emerged were documents that identified the fact that these abolitionists were also dealing with issues of equity, housing, voting rights, health care, jobs, education – you know, it’s very similar to what we still talk about today. And yet, these issues were very much part and parcel of their activism. So, for Black abolitionists, we find that they are not just concerned about this institution of slavery and its abolition and meeting the needs of freedom seekers, but they recognize the need for addressing issues of equity across the board. And while they’re doing all these things, they’re working full time. This story is much bigger and much more comprehensive than it is usually given credit for.

Lauren: Now, although these two communities are related, they differ in the way that the lots were given out, and also in the way that there was a more communal aspect to the Florence Farming Association, as opposed to where Timbuctoo was a little bit more individualized.

Devin: So, we tried to get an idea of what Florence, which is, again, in Oneida County, which is kind of a rural area – now what was Florence like, and what was Oneida County like in the 1840s? To get more information on that, we spoke to Rebecca McLain, the executive director of the Oneida County History Center.

Rebecca: Hello, I’m Rebecca McLain. The Florence Farming Association falls within our geographic boundaries of the history that we cover. And we are most recently associated with the site through Jessica Harney.

Jessica: I am a high school history teacher for Camden High School. My association with Florence has been through research that I’ve done personally, but I’ve also been able to involve my students in. I’m on the cabinet of freedom for the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum, and also have worked closely with the Oneida County Freedom Trail Commission.

Devin [to panel]: So how many people eventually settled in the community?

Jessica: It’s hard to say. What appears to be a big difference between the more notable Timbuctoo site is that the Florence site was a community. The men working in Florence incorporated into the Florence Farming and Lumber Association, and they’re promoting their site as a place where we’ll be able to have some of these shared resources, that we’ll be working together to develop the land. The newspapers suggest that they have divided some of the land up into to 100 village lots that contained a quarter of an acre each. So of course, that would not be enough to get individual voting rights. So, we kind of see a shift in the purpose and intention of this settlement, as opposed to what Timbuctoo was. There’s a total of about 25 acres that they’re working with, to divide up into those smaller 100 village lots. They’re also, in their newspapers, promoting that there may be 80-100 people living on site.

Basically, we’re limited by what we know for historical records. In terms of the 1850 census, and the 1860 census, we can begin to tell a story of who actually made their way and who was on the site in 1850. To get kind of a little bit more of a specific answer, when we look at 1855, which was the New York state census. And then we’ve further been able to break that down by finding a rare gem in some Oneida County archives. That was a random box of Florence records from 1853 to 1859. So that sort of helped us narrow the gap. And ongoing research is happening on that to be able to, you know, figure out exactly who is living there.

Devin [to panel]: Let me kind of get a broad view here and ask Rebecca: can you tell us what was Oneida County, like in 1840s and 50s? You know, who was already living there, who was maybe coming and going and what kind of industries there were?

Rebecca: Utica was kind of a growing city center, it had just become a city about a decade earlier, after the completion of the Erie Canal. You do see a lot of transportation throughout the county, we’re just in a good geographic point. And then I think a lot of the surrounding towns were still, I mean, just like it is today, you can get pretty rural pretty fast. In general, in the county, there would have been, in terms of demographics early on, German immigrants who have come through. And Irish.

Devin [to panel]: Was there a large African American community at this time?

Rebecca: In Utica, I think there was. It wasn’t huge, but there was definitely an African American population that was in Utica and Rome.

Devin [to panel]: One of the things that we found when we were doing our work on and speaking to people about Timbuctoo – so many of these African American families that tried to move there, they were the only African American people there, essentially. Do we have any record of like, what the local reaction was, or from the settlers themselves, what their interactions may have been with the neighbors? Because again, we had some examples up in Timbuctoo of negative interactions, and actually people stealing their land and telling them that their parcel began in a swamp, and you know, “Well, this isn’t very good farmland. So why don’t you just sell it to me? I’ll give you $1” or whatever. There was a lot of that happening there. So, any evidence of any interactions, good or bad?

Jessica: At this point in our research, we have not found anything overtly negative. Florence is being settled, I would say, pretty simultaneously by the Black Americans moving into this region. We also have Irish immigrants that are coming into the region as well. They end up staying, and they’re overwhelmingly still represented today, in the Florence community. What we do know is that they’re going to really lean on that Rome community for support. So, we know from the newspaper documentation that in October of 1849, Reverend Peterson out of Rome, also worked as an agent for the organization, he collected money and donations and materials from Massachusetts and Maine. And there’s a report of those items that were brought in. They listed a box of very useful books, a bag of very useful articles about farming techniques and things. So, it seems as though, at least from what is being produced in the newspapers, it seems positive. But again, we would be cautious to just look at what we have access to, because there’s always more to the story.

What we see here is a pivot away from Gerrit Smith’s initial purpose behind his gift, and we’re not completely sure how well supported that pivot was. But from here, we have a pooling of resources happening under the leadership of the Florence Farming Association. And we have, you know, a very well-structured governance over that organization. We have people that are serving as president, vice president, secretary of that organization. So there’s more to be pieced out about the functions of the organization. But we do know that they’re having meetings, and they’re doing a lot of self-promotion to get more people to move to the area.

Matt: Can I jump in a little bit with that? I’m Matt Kirk. I’m an archaeologist. I’ve been working in the Albany area for over 30 years now. And it’s important to know, too, that Gerrit Smith has the idea – he has the resources, but he’s not managing the properties on a daily basis. He’s selected a local individual, he puts him in charge of the land development, and it’s with him and Stephen Myers, who come up with the idea of exactly how to subdivide the property Smith owns. But he, it seems to me was a little bit concerned about the way Myers had developed these small lots.

Devin: The way that Myers set up the Florence farming Association definitely ruffled some feathers among his contemporaries, including with Frederick Douglass. Famously, in 1849, Douglass wrote Myers a letter basically criticizing him because he was not giving the land away, he was charging money for parcels. And Frederick Douglass felt that that was contrary to the ideas that Gerrit Smith came up with, and others. Myers wrote him a reply on March 17, 1849, and he really went out of his way to say that they were looking to build things like sawmills, and use the trees that they were clearing to create agricultural land, and have them made into lumber, which they would then sell. So it really is an attempt, as you noted, for a communal self-sustaining community – but there needed to be some sort of investment money up front. And the charging of money for the parcels was a way for Myers not to benefit himself or to get rich off from this, but instead to raise capital so that they could invest it back into the community. It’s an interesting difference between Timbuctoo, which was more of the original idea – “Here’s 40 acres for a family, and now go cultivate it and raise the value that way.” This was a little bit different. It was more of an idea about creating a sustainable community. And I think that’s why it was something that actually ended up being more successful in a way and lasting longer than Timbuctoo.

Matt: You know, there were 50-some-odd families that settled. A certain number of people remained for over a decade in Florence, which I think is somewhat remarkable, given the circumstances that were there.

Jessica: Stephen Myers seems as though he is doing a lot of a lot of the legwork from Albany. He’s doing promotion, because that’s what he’s good at, right? He’s a newspaper guy. He’s using his contacts that he has, and they’re targeting not just folks to move out of Utica and Rome, they’re really reaching as far south as Washington, D.C. They’re reaching New Bedford, Massachusetts, which is notable for some of the abolitionists, like Frederick Douglass, who came through that city. These are known Underground Railroad sites. And that helps paint the picture that this is more than a land scheme. This is more than about voting. This is also harboring folks that are trying to seek freedom. And there are some names that are really notable that go on to tell their story, what they were doing. And the one that comes to mind is Walter Hawkins. He was a resident for a number of years, and then he eventually went on and moved to Canada. But he became a well-known reverend, and a biography was written about him. And there’s an entire chapter on life as a farmer, living in Florence.

Devin [to panel]: Wow. Did Stephen Myers – I read the letter that he wrote March of 1849, to Frederick Douglass, and he mentioned that he was going to move to Florence. Do we know if he ever actually did that?

Jessica: We don’t know for sure.

Matt: He gave indications that it was his intent to move there. I think he even mentioned that he was going to try to start a newspaper in Florence. But my sense is that the reason that the settlement failed was from forces way outside of Stephen Meyers’ control.

Lauren: Though it was successful, there were outside forces that then led to the downfall of the community. And the main force was the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law that was passed in New York, that essentially said, “It didn’t matter where you were in a free state in New York, you could be brought down south back to slavery.” New York wasn’t safe for them anymore. A safer place to be would be Canada, and so by the end of the 1850s, there seems to be a real falling off of the Florence community. Although it’s possible that some people stayed longer, the vision that Stephen Myers had kind of comes to a close after the fugitive slave law and into the later 1850s and early 1860s.

Devin: That’s very true. And unfortunately, the Fugitive Slave Act was incredibly disruptive for both formerly enslaved African Americans and those who are never enslaved. Because basically, the burden of proof would have been on them to prove that they had not been a slave at some point. And there were these terrible stories of free Blacks being abducted and taken into slavery.

One of the things that is very interesting about Florence right now is how early on in the historical process we are, with the work of Jessica Harney and Rebecca McLain and archaeologist Matt Kirk. They’re very early on in establishing who was there, where these people may have gone, and then also uncovering the archaeology and the evidence literally underground of this community.

Lauren: This stuff’s hard to find. And it’s not like you can go to the archives for a day, and then you’ve got a story. Many of [the residents] leave and go to Canada for their safety. So what records are they leaving? If there are memoirs and family letters and things like that, they end up, usually, down in generation. So, until you find where those families go to, it’s very difficult to locate the documents that then give more of a glimpse into what Florence was really like. But that being said, there are records that turn up all the time. Jessica made reference to the box of documents in the county archives that inform them about the tax records for Florence. These are great finds, and it does happen in small archives around the state. I have personal stories about how you find a box on the shelf of something that you had no idea existed the year before, and now you have this treasure trove for researchers. So just because we don’t have a lot of documented evidence about the Black experience doesn’t mean that that will always be that way. And so, it’s great that they continue to do this research, and also that Jessica Harney is including her high school students in this research.

Devin: One of the issues that archaeologists Matt Kirk has, as you noted, the structures that were there were displaced or torn down in some cases – but also the land that made up the Florence Farming Association has changed hands over the years, many times in some cases. Most of it is now private property. But some of it is part of the state forest. And when we spoke to Matt Kirk, he told us a little bit more about some of the success they’ve had in uncovering remains of what might be the Florence Farming Association.

Matt: We’ve had success in locating at least three of farmsteads because they were reoccupied, some of them, by Irish immigrants afterwards. Part of our job is to tease out which archaeological deposits and features that we find were part of minor settlements and which were from later inhabitants. But in that way, I think we’ve also had some success. There are other properties that we think harbor additional archaeological resources. It’s on state land. So, there are regulations that protect these archaeological resources, and you need to file for what’s known as a 233 permit to do excavations. So, to this point, virtually all we’ve done is surface reconnaissance of walking through the forest with our volunteers and with the high school students.

We can measure success in a number of different ways. The one that I measure the most is that we have a really great partnership with Camden Central High School, where we get to take community members to this historical site that, especially now that the historical sign is no longer there, has no real physical presence in the community.

Lauren: So, if you happen to go to Florence Hill Road today, you won’t find the sign. In January of 2022, the local highway department reported that the sign had gone missing. Now, it’s unclear why this happened, but it’s not unique. Sometimes with historical markers, they do turn up missing. Sometimes it is innocent in that it gets hit by a snowplow or there’s a car accident, or sometimes the ground floods and it loosens up where the sign is. But other times, it’s purposeful destruction of historic markers. And that’s what it seems like it is in this case.

Devin: But the good news is there is a replacement on the way. Sometime in the summer of 2023, a new marker will be erected in the spot where the old one was. It will say the same text, and it will once again prominently show that the Florence Farming Association was part of the local history, and it will allow for students and others to perhaps learn more about it and discover more facts.

So, what do you do if a marker in your community is damaged or destroyed?

Lauren: It really depends on who erected the marker. In this case, the marker was erected by the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, and they were nice enough to offer half of the funds for a replacement, and then the organization wanting to replace the sign raised the other half. If it’s not a Pomeroy marker, the majority of those blue and yellow markers are often put up by State Ed or by local, either historical societies or towns, municipalities. In that case, it really is up to the municipality to replace the marker. I know that in our county, we’ve had some instances, like if it gets hit by a car, there’s car accident, that you can claim it on the insurance company and have it replaced that way. But if you were to go to Pomeroy and ask them to replace a sign that wasn’t erected originally by them, you would have to go through the full application process and prove what you wanted to say on the sign.

Devin: So, like every topic we deal with on this program, we are thinking about what does it mean today? What’s the legacy of the Forest Farming Association? And really, we touched on some of it: the importance of understanding that New York has a long history of racial discrimination in some cases, even in legislation like the 1821 act that required African American men to have a wealth of $250 to vote. But on a more local level, we asked our guests what their thoughts were.

Jessica: There’s actually several things that I hope my students take away from this. First and foremost, is that all the history that we study is local history as well. It’s literally in our backyard. This community exists eight miles from our high school. Something really, really hard was done here in this community for folks to try to start their lives, to be productive. Oftentimes, our students don’t see themselves in their history books. Being farmers in Florence is extremely relatable for my students. This is their family; this is their experience as well. I also really want them to understand and respect public history, making sure that they understand how I acquired the roadside marker for the community, understanding the research. And then we’ve worked really closely with the DEC, and I want my students to understand how to interact with the land that’s public land. I’m very grateful that my school district and my students have gotten behind this and support all this work that we’ve been able to do.

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.