On this episode, Devin and Lauren learn about an enclave of restaurants, bars and resorts that catered to predominately Latin American clientele near the Catskill Mountains. As more and more Latinos immigrated to New York City for work, they began to look to places outside the city for recreation and to connect with other Spanish-speaking tourists. By the mid-1950s there were 50 resorts in the Plattekill area that focused on Spanish-speaking visitors.

Marker of Focus: Las Villas, Ulster County, Plattekill

Guests: Ismael “Ish” Martinez, author of Las Villas of Plattekill and Ulster County; Jimmy Castro, Founder/CEO of Ritmo Caribe Promotions and director of Back to Las Villas

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.

Further Reading:

Ishmael “Ish” Martinez Jr., Las Villas of Plattekill and Ulster County

Christina Perez Jimenez and J. Bret Maney, The Latino Catskills Project

Sherrie Baver, Angelo Falcón and Gabriel Haslip-Viera (editors), Latinos in New York: Communities in Transition

Benjamin Lapidus, New York and the International Sound of Latin Music, 1940-1990

Teaching Resources:

Columbia University Institute of Latin American Studies K-12 Outreach Program

National Endowment for the Humanities EDSITEment Hispanic and Latino Heritage and History in the United States

New-York Historical Society & El Museo del Barrio Nueva York Classroom Materials

NYC Public Schools Hispanic Heritage Month

Follow Along

Devin: Welcome to A New York Minute in History. I’m Devin Lander, the New York state historian.

Lauren: And I’m Lauren Roberts, the historian for Saratoga County. On this episode, we’ll be talking about a marker located in the town of Plattekill in Ulster County. Located in the Catskills region of the state, this marker sits at the intersection of Huckleberry Turnpike and County Road 13, which is also known as Plattekill Ardonia Road. And the text reads: “Las Villas. Named given Plattekill and Catskills resorts offering Latin music, food and culture from circa 1914. This road gateway to their locations. William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 2020.”

So before we started working on this episode, I had never heard of las villas before. I wasn’t aware that there was an area of the Catskills that catered to Latino and Hispanic people. So I spoke with Ish Martinez, who grew up at las villas, and he helped us to understand what “las villas” actually means.

Ish: My name is Ishmael Martinez Jr, and I actually grew up in one of the villas that my parents owned. So that’s what gives me most of my background about the villas. Aside from that, I did a lot of research once I decided that I was going to write a book about las villas. I felt it was something that was important. I felt it was an interesting and an important era for our town, and for Latinos in general.

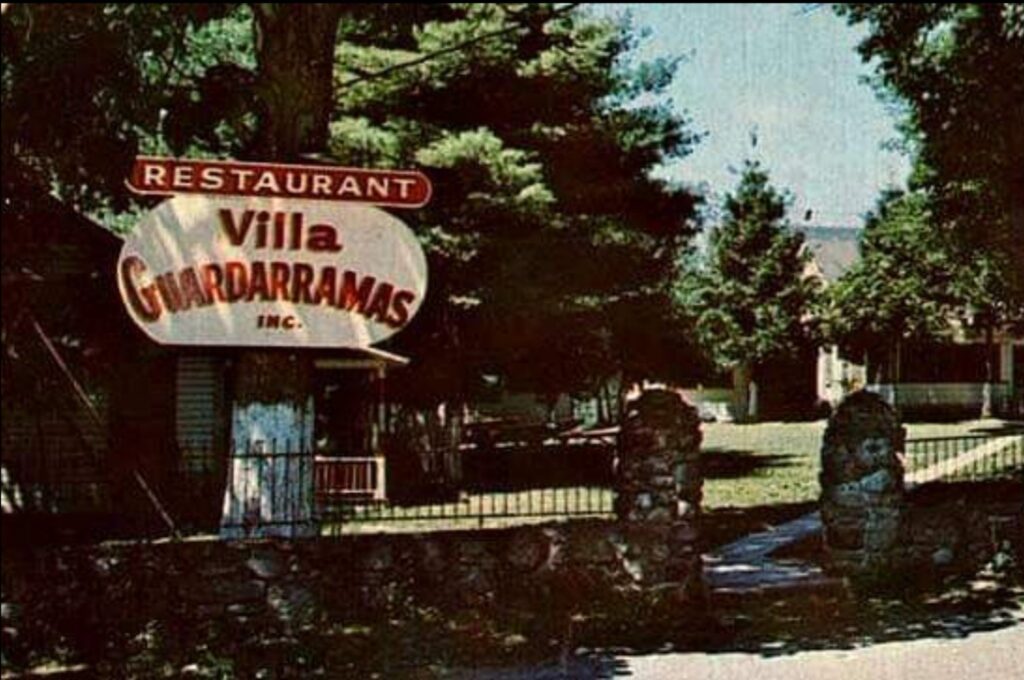

“Villa” itself, it’s a kind of a polysemous word. It has many meanings. It can mean “country house,” it can mean “country estate,” it can even mean “small village.” But in in the context of the villas, it was more or less a country house. As you may know, the Catskills and the Hudson Valley has always been an area of retreat, and resorts, and people going out to see the scenery and get the fresh air. And at the time, farms were coming up for sale. It wasn’t very far from New York City. And so Plattekill just happened to be the place — it was kind of random — to spend time in the country in these country houses.

Devin: Las villas was a new topic to me as well. I had no idea that this group of resorts existed in in the Catskills — and existed for as many decades as they did. The marker references 1914, but there’s some evidence that some of the early villas began as early as 1912. And these were established, first, by Spanish people, who were residing in New York City and looking for a place to get out of the city. Especially in the summertime, it gets a little oppressive down there. And they were looking for somewhere in the countryside where they could meet as a group and go as families and friends. That’s really the genesis for this. And then it exploded by the 1930s and 40s, and especially the 1950s. As more and more people gained access to transportation, cars, and even buses were used to bus people from the city up to Ulster County by the hundreds. [Las villas] really took off, and they eventually numbered over 50.

Lauren: When I spoke with Ish Martinez, he talked about how his parents got started in the las villas community.

Ish: My mother was a born in Brooklyn to Puerto Rican parents, and then she moved to a place called “el barrio.” And some people might be familiar with that. It’s Spanish Harlem, between 90th Street and 116th Street, in general, on the East Side of Manhattan. And it had a very large Hispanic community, mostly Puerto Ricans, but there were some Spanish [people], there were Cubans, and then later on Dominicans and South Americans. So my parents met in el barrio, and that’s where they grew up. Early on in the 40s, they were actually customers to las villas, and they used to come up to Plattekill to a place called Villa Rodriguez, and Villa Rodriguez was the first villa, as far as my research tells me, that was established in particular around the 20s. My parents started coming up there in the 40s, and they enjoyed it so much. They loved the area. And at some point, my dad just decided that they wanted to move to Plattekill, and they bought a farm. They started out as farmers — that lasted only a year or two — there were chickens and some cows and pigs. But with all the villas already established in the area, they saw that as a better alternative for them. And they quickly turned it into a villa. My dad, having had a carpentry background, built most of the villa, aside from the original farmhouse that they had. He built rooms, dining halls, dance halls, and the bar.

Lauren [to Ish]: And so did you continue to live in the farmhouse part of it?

Ish: We did at first. They bought the business in 1948. By 1955, we had moved full-time to Plattekill. Before that, we would come up on weekends and whenever we could, because my dad was still working in New York City. But then finally, when we moved up, he built a house for us to live in. So we built our own house — my father, sister, and her husband also moved up and built a house. So we had our own home, and then the villa had the buildings that accommodated all the rest.

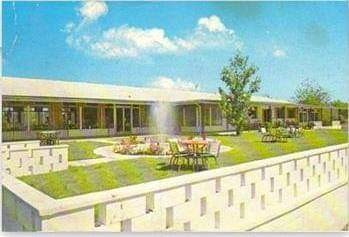

The name of the villa was Sunny Acres Hotel. It was funny, because the name was invented by my father’s sister, my aunt Stella. And she had seen the name in the funny papers. Somewhere she saw a farm called Sunny Acres, and so she brought that to his attention. They liked the name, and the name stuck. And even though it doesn’t have a Latino ring to it, you know, you get a lot of variations on what people called it based upon whether they have an accent or don’t have a Spanish accent. But yeah, that’s the name of it. And it went on for about 22 years. It was around for a while.

As a child of villa owners, naturally, you are expected to do your share in taking care of the villa. So, my jobs were numerous. I took care of the swimming pool. I mowed the grass, I trimmed the hedges. I cleaned inside — and now, I’m not just talking about me, but our entire family. I have two older brothers, Ron and Larry. I have a younger sister, Carla. We were a true villa family. We all had our part. We all did some work to some extent. My mother certainly worked in the kitchens and took reservations. My dad was kind of like the host with the most, he just had to show up, and it seemed like everyone in town knew him. I couldn’t tell you how many people from the city would ask for him by name.

Lauren [to Ish]: I have to imagine that most of the people coming out of the city didn’t have their own automobiles, because most people in the city don’t. So how are people getting to las villas?

Ish: That is true. Early on in the 20s and 30s, the best form of transportation for many people was actually by boat. They would take boats, sometimes day liners. They would go to the port of Newburgh and Kingston, and from there, they could catch either a bus or, in the case of Kingston, there was a rail line that went out along the Route 28 corridor, where a number of these villas also existed. In Newburgh, there was bus transportation to Plattekill, and to other areas that would bring them to the villas. Of course, over time, as the highways got better, and roads get better, and people were able to afford cars, then bus and cars were the main forms of transportation. The buses in particular, in Spanish, they were called “jiras.” J-I-R-A-S. And basically what that was, it was people chartering buses to get them to the villas. And they would come up in droves. I mean, you could get a bus ticket for between $4-$6. At one point, you would see the roads back-to-back with traffic, I mean, bumper to bumper. And a small town like Plattekill almost couldn’t take as much transportation as it was getting. So it could be problematic, also, but people seemed to tolerate it.

Lauren [to Ish]: Was it more common to go out for the day, like a day trip? Did it vary?

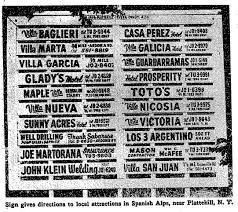

Ish: Yes, it did. It did vary by family. As I mentioned, the ones that brought up the jiras, the buses, those are generally just daytime visitors. But there were people that had their own cars, and they would come up, and they might stay for a day or they might stay for the weekend, which was when most of the activity was going on in terms of music and so forth. My parents had many visitors who would come up and stay for a week. And so did some of the other villas that were a little bit larger, like the Villa Nueva, the Villa Garcia, the Villa Galicia, and there were several others, the Villa Madrid, the Villa Victoria. So those are places that had week-long visitors. And generally, there would be things for them to do, there would be swimming pools, playgrounds and basketball courts.

In my parent’s villa — and I should mention that their names were Ishmael and Lucy Martinez. My dad went by the name of “Shorty,” though, for obvious reasons, if you knew him. He was pretty innovative. My dad, he had a lot of ideas about bringing people in, he made sure that there was always some form of entertainment going on to keep the people at the villa when they got there. Because a lot of people would do the “villa hopping:” somebody came, they heard a band, when the break came, they would scurry over to another area where maybe the music was still going on. And of course, there were places to eat. My parents had a restaurant as well. But [my dad] believed that if you kept the people there, they would tend to spend more. And so you would have day and night entertainment. It would start in the afternoon and go all the way — on Saturday night, it would go until 2 a.m. with the bands playing, until the law required that the bar had to close down.

Lauren [to Ish]: Was this one of the premier places where Latinos could kind of celebrate their culture, where there might not have that available to them in the city? Was it kind of a cultural experience as well as a vacation for them?

Ish: Yes, it absolutely was. It was a place where they could congregate and get together and you know, share their culture, the language — and actually, as I mentioned, most of them came out of the city and the New York metropolitan area. So we had people coming from Connecticut, people coming from New Jersey. You had people that had a great allegiance to one villa, and they got to actually know the owners, and even the employees that the villa employed, and it kind of became like a family to them. And there were other people who might test out the waters and try one villa one year and wouldn’t be the next. But yeah, you have many loyal customers who would come to the same villa.

Lauren: There was a lot of variety in the villas as well. Some of them were very small, one room, with more of a club-like atmosphere. And then other villas were much bigger, and were more resort-like. You could rent a room there, they had pools and playgrounds for the kids. Some of them had more of a family atmosphere rather than just the nightlife. In general, families seem to come out of the city together and enjoy this, whether it was a day trip — he mentioned that churches would often charter buses so that the church community would go for the day and listen to the music, and have the food, and then head back to the city. But also, there were some people that would go away for the week. So it really varied, and they were all pretty much seasonal: they would start in May, they would close in early fall.

Devin: I think it’s interesting, too, that we see, as I noted earlier, that the original villas were created by Spanish people, and then as immigration patterns change in New York City, and there’s an influx of Cuban people or Cuban Americans in New York City, they start to come to las villas, in some cases, purchasing their own resorts and taking that over. And then in the 1940s, 50s, and into the 60s and 70s, it starts to be predominantly Puerto Rican immigrants and people of Puerto Rican descent who are spending time in las villas. And I think this is really interesting and indicative of the immigration patterns, again, in New York City, and in New York state itself. It’s also very interesting to think that Plattekill is a very small town, and not necessarily a diverse town, either. But because of people establishing businesses and then hundreds and thousands flocking to those businesses every summer, it really becomes a very diverse place, and a very economically successful place.

Lauren: And they were all kind of along one road, because all of these people that were coming up on buses didn’t have transportation once they got there. So a lot of the villas had to be within walking distance. He said they called it “villa hopping,” where they could go from villa to villa. And he talks about how his father was clever about keeping people at his villa, because he would have one band play a set, and then when they took a break, another band would pick up their break, so that nobody was leaving in between sets. He wanted to have everybody dancing all the time.

Devin: That’s a great point. I mean, one of the most interesting and historically significant parts of the story is the fact that las villas became an epicenter for Latino, and specifically salsa, music. There were so many prominent musicians that either got their start there, or at least spent time playing there. And you noted it was because villas were trying to keep as many people there as they could. So they were doing it by trying to attract the best bands, having more bands, also having the best food and cuisine, because that was a huge part of it. I visualize this as a town-wide Latino festival: it’s music, it’s open grills, and people dancing and drinking and going from site to site and really trying to take it all in during the amount of time that they have there. As you noted, some people didn’t have more than maybe one night there, and other people stayed longer.

To get an idea about the importance of las villas for the musicians who were working in New York City and trying to establish a name for themselves, I spoke with Jimmy Castro, who is a music producer and promoter, and also a filmmaker who made a film called Back to Las Villas.

Jimmy: You didn’t think about it that much back then. But when I think about it now, it was just so incredible. It was a unique place, you know, a place that was just second to none. There was no nowhere else like it. You know, there was legendary artists today that you name, and they actually started their careers playing in la villa, you know? People like Larry Harlow, Yomo Toro, Hector Lavoe. They were known back then, you know what I mean? And a lot of them, a lot of Latin music legends that, you know, were based in New York at that time, would take the trip just to get out of the city. I mean, they played a lot in New York City, of course, but you know, just to get out of the city every now and then they would travel up to las villas and perform.

Devin [to Jimmy]: They seem to have played a major role not only as a venue, but as a way to get the music out into even larger audiences.

Jimmy: Yeah, that was the thing. A lot of it was word of mouth. Also, you know, these artists coming from New York City driving up on weekends to perform, again, weren’t as well known as they are now — and some of them aren’t even with us anymore. It was word of mouth to people that visited las villas, and were able to see these artists perform, get to know them. They became fans. The fanbase, of course, grew from them performing in las villas, yes, because a lot of the people that went to las villas, a majority of them are from New York City. They’re also driving up.

If you’re driving into the town, and you get into the town, and you roll down your windows, you literally hear the music. A lot of the reason it was so popular was because it reminded a lot of people of Puerto Rico, you know, their home, where they came from. And going to las villas was like, you know, they even called it “little Puerto Rico.” So, that’s the kind of thing that I remember about it. And then, during the production, I reached out to a lot of people asking if they had pictures, videos or anything like that to send me, and I got so much stuff, a lot of stuff I couldn’t even use. It was so much, everybody sending me things from all over the world. I’m telling you, from all over the world, I was getting pictures and stories, and I couldn’t keep up with it. I mean, I had a really small production team, but you know, producing a documentary, it’s really a lot of work, man.

Before I started working on the production itself, I needed to find a narrator for it. Because a documentary has to have a narrator. And I didn’t know who I would get. I was trying to think of who can I reach out to, to narrate this. And one night, I was actually in my home, watching the news, Fox News 5 from New York. And one of the meteorologists, her name is Audrey Puente. She’s actually the daughter of the famous Tito Puente, the timbales player, right? I was listening to her, you know, doing the weather. And I said, “Man, wouldn’t it be great to have her? Because her father performed there.” And I sent her a message. And I was so surprised that she really got back to me right away. I called her I explained what I was doing. She didn’t hesitate. She said, “I’m in, Jimmy.” And so that’s how she became, you know, the narrator of this documentary.

Lauren: What is considered to be the golden era, when las villas was the most popular, would be between the 1950s through the 1970s. And once you get into the 1980s, and certainly into the early 90s, it really drops off, and there are less and less villas and less people visiting, largely because it’s much easier and more affordable to travel by airplane. And there are other places that are centers of Latin culture such as Florida, where people are frequently visiting, rather than Plattekill.

Travel patterns change. Being from Saratoga Springs, like, after the Victorian era, when everybody started to get their own automobiles, they didn’t have to take the train anymore. You know, Broadway was on a downward spiral for a while. So the same is true here.

Many of the people who live in Plattekill now, or in the area, may drive by the area that was known as las villas and not even know what used to be there. And because of this, Ish thought it was important to mark, with a historic marker, the location, and to remember what had been such a huge part of that community.

Ish: I would be remiss if I didn’t say that this all got kicked off by my sister, Carla Ramos, who started up Facebook page, called “Las Villas of Plattekill.” And that really brought to mind that it was the right time to write the book and to start giving las villas more exposure. Aside from my book, that wasn’t anything obvious in the town to tell people that the villas once existed there. I was always interested in [historic] markers and would always stop to read them. And I thought just to myself, you know, “That would be a good way to bring the story of las villas, at least to the attention of people driving through the village or living in the village.”

There’s a place in the village where there existed a general store. And that was kind of the center of the village. It was the crossroads, really, of people coming through the village, and either continuing up Route 32 to northern Ulster County, or taking the Plattekill Ardonia Road where many of these villas actually were established. It was like our malt shop when we were growing up. And back, when the villas were around, there was an organization that was formed by the villa owners called the Plattekill Tavern Owners Association. And as part of that association, they created one large sign with all the names of the villas and businesses on it. And that sign was located right there, near the general store. And I just felt that crossroad would be a good spot to put the sign.

Lauren [to Ish]: Have you had more people asking about the history?

Ish: I’ve received a lot of positive feedback from the locals in the town, both Latinos and non Latinos, about the sign. And now there’s a certain amount of pride for having that there because, as it turns out, that sign — and it’s amazing to me — it’s the only historical sign in the town of Plattekill. So I think it has given some exposure and some feedback on the history of las villas. I’m glad it’s there.

I think of the environment that I grew up in, and I think about Villa Sunny Acres in its totality, just what it looked like, and you know, that will forever be preserved in my memory. Even though today if you were to go back there, it looks much, much different. The dining room, dance hall, and the bar, that building burned down in 2006. But when I think back about it, I always think about the property in its entirety and all the things I did there as as a child. I think of the swimming pool, and I think of the pond which had rowboats. I think about the dance hall, and how much time I spent there. Actually, as I think about it, when you’re in it, you think it will never end! I mean, you see thousands of people flocking to the villas in buses and in cars. Everything was crowded, and there was so much going on. It just felt like it will never end. But you know, things come to an end, and that’s just life I guess.

A New York Minute In History is a production of WAMC Northeast Public Radio, the New York State Museum, and Archivist Media, with support from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. This episode was produced by Jesse King. Our theme is “Begrudge” by Darby.